Executive Summary

Income-Driven student loan repayment plans, which started with Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) in 1993, can make monthly repayment substantially more affordable for many borrowers by limiting student loan payments to no more than a certain percentage of income. However, when considering any of the five Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans, it’s critical to think not only of how borrowers may manage the monthly repayment costs but also of the long-term income trajectory of the borrower. Since payments are based on income, those who expect high future earnings may not benefit from using an IDR plan; because payments increase proportionately with income levels (and depending on the interest rate(s) of the loans being paid off), the borrower may or may not be better off maintaining lower monthly payments than paying the loan off quickly with higher payments. Which makes the decision to choose an IDR plan potentially complex, especially since many repayment plans for Federal student loans not only limit monthly payments relative to income but may also actually trigger forgiveness of the loan balance after a certain number of years.

Accordingly, the first line of action for borrowers tackling student loan debt and its potential repayment strategies is to identify the specific goal: to pay the loan(s) off in full as quickly as possible and minimize the interest expense along the way, or to seek loan forgiveness and minimize total payments along the way (in order to maximize the amount forgiven at the end of the forgiveness period)? Once the objective is clear, planners can explore the repayment options available.

For those seeking the path of loan forgiveness, IDR plans that limit current payment obligations are often preferable, as even if they lead to the loans negatively amortizing (as the interest accrual on the student loans may significantly outpace the required payment if a borrower has a relatively low income), doing so simply maximizes forgiveness in the end. On the other hand, debt forgiveness may not be best; if the borrower does stay on that IDR plan all the way through forgiveness (typically 20 or 25 years), the forgiven amounts may be treated as income for tax purposes (which for some borrowers, could actually bring the total cost to far higher than what they would have paid had they actually paid down their loan balance to $0!).

Ultimately, the key point is that repayment strategies should be chosen carefully, as the desire to manage household cashflow often entails minimizing payments that maximize forgiveness, but the income tax consequences of forgiveness and rising repayment obligations as income grows can sometimes result in higher total borrowing cost than simply paying off the loan as quickly as possible!

Understanding Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans For Federal Student Loans

The Federal government has provided education-based loans for decades, under a variety of different programs, which generally differ depending on when the loan was taken out, who took out the loan, and the purposes of the loan. While the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program was the most common source for loans up until 2010, the Healthcare & Education Reconciliation Act has since phased out that program. All Federal government loans today are provided through the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan program, often referred to as simply “Direct Loans”.

Traditionally, when a borrower with Direct and/or FFEL loans leaves school, there is typically a 6-month grace period in which no loan payments are due. After the 6-month grace period, though, borrowers are placed on a 10-Year Standard Repayment plan, for which monthly payments are based on the outstanding debt amortized over 120 months at the applicable interest rates.

However, many borrowers are unable to afford the payments set by the 10-Year Standard Repayment timeline. Recognizing that particularly in the context of student loans, it’s difficult to otherwise determine what a ’reasonable’ (or feasible) repayment obligation will be when the loan (and payment obligations) are incurred before the borrower finishes school and finds out what job they’ll get (and what income they’ll earn) in the first place. Given this uncertainty, the government introduced Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans as another option to facilitate manageable repayment terms.

Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans all have the same premise: rather than simply setting the repayment obligation for a loan based on the interest rate and a given amortization period, the repayment obligation is calculated instead as a percentage of the borrower’s discretionary income (generally based on Adjusted Gross Income and Federal poverty guidelines).

Accordingly, student loan borrowers pursuing IDR plans must file paperwork to recertify their income (and family size) each year, and their monthly loan payments are subsequently adjusted accordingly based on their income levels. Which not only helps to ensure that the student loan payment obligations themselves remain ‘feasible’ for the household but also allows those who may otherwise default on their loans to keep their loans in good standing and preserve their credit scores.

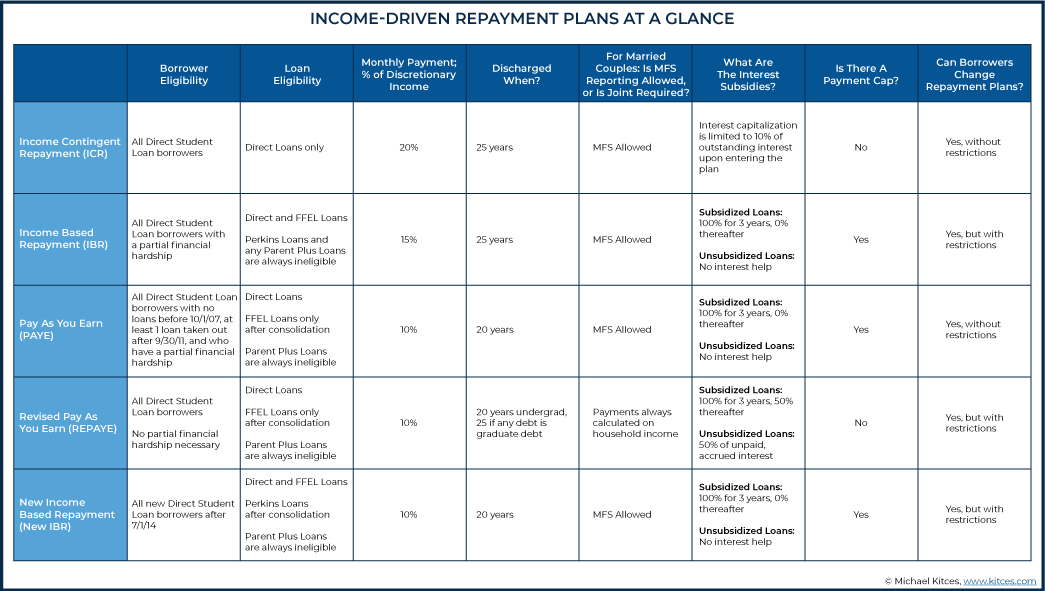

In practice, though, the individual rules for various IDR plans vary significantly, and choosing the best IDR plan can be a challenge because each of the repayment plans varies across eight different key criteria:

- Borrower Eligibility – Aside from having qualified loans eligible for a repayment plan, borrowers may also be required to have at least a partial financial hardship or a specific time frame in which they took out their loan to be eligible for the program.

- Loan Eligibility – While all Federal Direct student loans are eligible, FFEL loans can only be repaid with Income-Based Repayment (IBR) and New IBR plans, while other loans can be repaid only if they are consolidated into a Direct Consolidation loan.

- When Remaining Balance Is Discharged – The amount of time before loan forgiveness is granted generally ranges between 20 and 25 years. However, some individuals may qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, in which case loans can be forgiven (tax-free, in contrast to IDR plans) in 10 years.

- Monthly Payment Calculation – Payment amounts are based on a certain percentage (ranging from 10% – 20%) of discretionary income, which is a borrower’s total Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) minus 150% of the Federal poverty line (and thus depends on the borrower’s state of residence and family size).

- Payment Caps – Some IDR options have a cap on how much loan payment amounts can be increased due to changing income levels, which benefits individuals with income levels that increase very quickly after entering the repayment program.

- Income Reporting Requirements – Some repayment plans require that total household income be included in calculating monthly repayment amounts, while others only look at the income of the individual (even if part of a married unit, which can make Married Filing Separately status appealing for payment calculations).

- Interest Subsidy Limits – Most plans will subsidize up to 100% of loan interest for up to three years on subsidized loans, and generally don’t subsidize interest on unsubsidized loans. For Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plans, interest capitalization is limited to 10% of outstanding interest upon entering the plan (making any interest that would have accrued beyond that threshold a form of interest subsidy).

- Restrictions On Switching To Other Repayment Plans – Some repayment plans have restrictions or specific rules that must be followed in order to switch between IDR plans (increasing the importance of choosing the ‘right’ plan upfront), while others have no such restrictions (other than capitalizing the interest outstanding).

Let’s look at each IDR plan option, and their rules, across each of the aforementioned criteria.

Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) Plan

The Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plan originated in 1993 as one of the first IDR plans. Notably, because other IDR plans have become more generous to borrowers since this plan first arrived, ICR is almost never the repayment plan of choice today.

For example, ICR requires the highest monthly IDR loan payment amount, accommodates the lowest level of interest capitalization across repayment plans, and permits repayment of Direct loans only (while Federal Stafford loans, FFEL Loans, FFEL Consolidation Loans, and Perkins loans are not eligible loan types for ICR, they can qualify if they are consolidated to a Direct Federal Loan).

Fortunately, though, because ICR has no restrictions to change plans, it is relatively simple for borrowers to opt into more favorable repayment plans (though whenever a borrower does change repayment plans, any outstanding unpaid interest is capitalized).

That being said, even though ICR is the least generous plan currently available, more people are able to qualify for this plan compared to other IDR plans as there are no income requirements for ICR.

The annual payment amount for ICR is determined by calculating 20% of the borrower’s discretionary income (which is defined as Adjusted Gross Income minus 150% of the Federal Poverty Line for the borrower’s family size).

Although there is technically another calculation that can be used, which bases the payment amount on a 12-year fixed loan adjusted for the borrower’s income, the amount using this method is always greater than the first option above, so in practice, this calculation is never used.

Repayment amounts under ICR are not static, though, and as income increases, so do ICR monthly payments, with no cap on how much they may increase. Thus, ICR may not be the best option for borrowers who expect their incomes to rise dramatically over the lifetime of their loans.

While ICR plans originally did not allow married borrowers to report their income alone, separate from the rest of their household, the plan has been amended since to allow the use of income reported using MFS tax filing status.

After 25 years of payments in the ICR plan, outstanding loan balances will be forgiven. That forgiveness is considered taxable income for the amount forgiven (including both remaining principal, and any interest that has accrued on the loan).

The ICR plan does not offer any interest subsidization beyond capitalizing up to 10% of any unpaid interest on loans upon initial entry into the plan (which is added to the principal loan balance).

Income-Based Repayment (IBR) Plan

Income-Based Repayment (IBR) plans were established in 2007 as a need-based repayment plan, introducing a partial financial hardship requirement for the first time. Borrowers were first able to start using IBR plans in July of 2009.

According to the studentloans.gov website, “partial financial hardship” is defined as follows:

… a circumstance in which the annual amount due on your eligible loans, as calculated under a 10-Year Standard Repayment plan, exceeds 15 percent (for IBR) or 10 percent (for Pay As You Earn) of the difference between your adjusted gross income (AGI) and 150 percent of the poverty line for your family size in the state where you live.

Notably, IBR plans do not define a “partial financial hardship” as anything more than having payments so high that a borrower would need and benefit from a percentage-of-income limitation in the first place.

In addition, since IBR’s “financial hardship” for eligibility is defined as payments that exceed only 15% of discretionary income (again, discretionary income is the difference between AGI and 150% of the applicable Federal poverty line), compared to the ICR plan which caps payments at 20% of discretionary income, anyone eligible for ICR and the more recent IBR plan would typically choose an IBR plan.

As noted earlier, borrowers using IBR plans must have a partial financial hardship. Two useful tools to determine qualification and repayment amounts can be found here:

Both subsidized and unsubsidized Direct Loans, Direct Consolidation Loans, Direct PLUS plans, and FFEL Loans are eligible for the IBR plan. Perkins Loans can be eligible if they are consolidated to a Direct Loan, whereas any Parent PLUS loans are never eligible, even if consolidated to a Direct Loan (which means that Direct Consolidation Loans and FFEL Consolidation Loans that were used to pay off a Parent PLUS Loan would not be eligible for IBR plans).

The formula for annual IBR payment amounts is very similar to that of ICR payments, except that it is based on only 15% of the borrower’s discretionary income.

Additionally, payments on IBR plans cannot be larger than what a borrower would have paid entering a 10-Year Standard plan at the moment they entered IBR. This limits the risk of someone having their income increase dramatically in the future, only to see their future required payment balloon larger as well.

IBR plans also permit borrowers to report their income separately from other household income, which means they may benefit married borrowers to file with MFS status in order to have their percentage-of-income threshold applied to a lower base of just one spouse’s income.

Outstanding loan balances under IBR are forgiven after 25 years of payments. As with all other IDR plans, forgiveness amounts are considered taxable income.

When it comes to interest subsidization, the Department of Education (DOE) covers all interest for the first 3 years on subsidized loans. For unsubsidized loans and subsidized loans beyond the first 3 years, interest is not subsidized.

Borrowers who decide to switch out of an IBR plan to another repayment plan must be mindful of some restrictions. Namely, they would need to enter into a 10-Year Standard Repayment plan for at least 1 month or make at least one reduced forbearance payment (where a borrower can put their loan into “forbearance” status, which effectively reduces the loan payment amount temporarily, and then making one payment while in forbearance before switching to their new IDR plan). The reduced forbearance payment can be negotiated with the loan servicer and can potentially be very low. Furthermore, whenever a borrower changes repayment plans, any outstanding, unpaid interest is capitalized.

Pay As You Earn (PAYE) Repayment Plan

Pay As You Earn (PAYE) became available to eligible borrowers in October of 2012, with the intention of offering some relief to new borrowers facing soaring college costs (though it was not made available to many previous borrowers).

Like the IBR plan, PAYE also requires borrowers to have a partial financial hardship (again defined as student loan payments in excess of specified percentage-of-income thresholds). In addition, borrowers must have no outstanding student loan balance as of October 1, 2007, and at least one Federal student loan that was disbursed after October 1, 2011 (i.e., they must have become student loan borrowers more recently).

PAYE Repayment plans will accommodate both subsidized and unsubsidized Direct Loans, Direct Consolidation Loans, and Direct PLUS plans. While Perkins Loans and all FFEL Loans are ineligible, they can qualify if consolidated to a Direct Federal Loan.. In addition to FFEL Parent PLUS loans, Direct Parent PLUS Loans and Direct Consolidation Loans that paid off a Parent PLUS Loan are also never eligible for PAYE plans.

Annual PAYE payment amounts are equal to 10% of the borrower’s discretionary income, which is lower than both ICR (at 20% of discretionary income) and IBR (at 15% of discretionary income). Similar to IBR payments, PAYE plan payment amounts cannot be larger than what a borrower would have paid entering a 10-Year Standard plan at the moment they entered PAYE. This again limits the risk of someone having their income increase dramatically only to see their required payment balloon higher as well.

Like ICR and IBR, PAYE borrowers are allowed to report income separately using MFS filing status.

For PAYE, outstanding loan balances are forgiven after 20 years of payments, in contrast to the longer 25-year forgiveness period of both ICR and IBR plans. The total amount of forgiveness will be considered taxable income.

Interest subsidies are the same as for borrowers using IBR – for subsidized loans, the Department of Education (DOE) covers all interest for the first 3 years. For unsubsidized loans (and subsidized loans beyond the first 3 years), interest is not subsidized.

Borrowers can easily change to other Federal repayment plans as there are no restrictions to do so (like switching out of ICR plans), nor is there a requirement to go onto the 10-Year Standard plan for any period of time. However, whenever a borrower does change repayment plans, any outstanding, unpaid interest is capitalized.

Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) Repayment Plan

The Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) plan became available to borrowers in December of 2015 and expanded upon the list of eligible borrowers who were able to benefit from the generous terms of PAYE (at least in comparison to ICR and IBR plans, which both have higher payment amounts and longer forgiveness periods than PAYE).

However, REPAYE has some significant downsides compared to PAYE. In particular, REPAYE is the only repayment plan that does not permit married borrowers from reporting their individual income separate from their household income. Even if a borrower files their taxes using MFS status, payments will be based on total household income. This makes REPAYE much less attractive to borrowers with spouses earning significantly more than them.

Unlike the PAYE plan, which is only available to ‘more recent’ student loan borrowers (those with a disbursement since 2011), REPAYE is available to all Federal student loan borrowers, regardless of when they took out their loans or if they have a partial financial hardship. This means that borrowers who are ineligible for the PAYE Plan because they have pre-2011 loans can still choose to switch into the REPAYE Repayment plan.

Loans that are eligible (and ineligible) for PAYE are identical as those for REPAYE.

REPAYE payment amounts are the same as PAYE amounts (10% of the borrower’s discretionary income). However, unlike PAYE, there are no caps on how much payments can be increased, so payments can grow well beyond where they would be capped for borrowers on other repayment plans. This makes REPAYE a risk for borrowers who have substantially higher future earning power (and thus see their future payment obligations rise with their future income, limiting their ability to carry a balance to be forgiven in the future if so desired).

For REPAYE plans, outstanding loan balances are forgiven after 20 years of payments (like PAYE) if all loans are undergraduate loans. However, if there are any graduate loans, the forgiveness period is 25 years (like IBR and ICR). These forgiveness amounts are considered taxable income.

Interest subsidies for REPAYE plans are expanded and more generous than those under other repayment plans. For Direct Loans that are subsidized, the DOE continues to cover 100% of the interest for the first 3 years after entering into a REPAYE plan. While this is also the case for PAYE and IBR plans (both the original and new IBR plans), what’s unique about REPAYE is that after three years, the DOE continues to subsidize 50% of the loan interest, whereas other plans (except for ICR, which does not subsidize interest after plan entry) offer no subsidization of interest after three years. Additionally, REPAYE plans will subsidize 50% of unpaid, accrued interest for Direct Loans that are unsubsidized, in contrast to other plans that provide no interest help for unsubsidized loans.

Example 1: Kyle has a subsidized Direct Student loan with a balance of $50,000 and an interest rate of 6% per year.

Based on his income, he is required to pay $2,500 per year. However, $3,000 of interest accrues annually.

The government will cover 100% of the $500 difference ($3,000 interest expense – $2,500 payment amount ) in the first 3 years of repayment.

In year 4 and beyond, however, only 50% of the $500 difference will be covered by the government, or $250.

This limits (but does not prevent altogether) the growth of the borrower’s balance due to negative amortization, which is a significant problem under PAYE and IBR.

Additionally, switching from REPAYE to another repayment plan is not as simple as switching out of PAYE (which has no restrictions). Borrowers changing out of REPAYE face the same restrictions as those changing out of IBR; namely, they must enter into a 10-Year Standard plan for at least 1 month or make at least one reduced forbearance payment. Again, the reduced forbearance payment amount can be negotiated with the loan servicer and can potentially be very low.

In all cases, whenever a borrower changes repayment plans, any outstanding, unpaid interest is capitalized.

New Income-Based Repayment (New IBR) Plans

The New IBR plan was passed as part of the 2010 Health Care & Education Reconciliation Act and became available in 2014. It combines some of the most generous aspects of each of the previously-available plans by lowering the required payment, shortening the timeline to forgiveness, and allowing the use of MFS tax filing status.

However, while it’s the most borrower-friendly plan, very few people are eligible for it yet, as it is only eligible to recent student loan borrowers and cannot be switched into for those with older student loans. New IBR plans are limited to borrowers who did not have a loan balance as of July 1, 2014, but offer repayment of the same loans as the old IBR plan.

New IBR payments differ from old IBR payments in that they require a lower percentage of income to be paid; whereas the old IBR plan is based on 10% of the borrower’s discretionary income, new IBR payment amounts are only 10% of the borrower’s discretionary income (the same as PAYE and REPAYE payment amounts). Like the old IBR plans, New IBR plans cannot be larger than what a borrower would have paid entering a 10-Year Standard plan at the moment they entered the plan, limiting the risk of dramatically increasing repayment amounts with increasing income levels.

For New IBR plans, outstanding loan balances are forgiven after 20 years of payments, which is fewer than the 25 years required by the old IBR. That forgiveness is considered taxable income.

As far as interest subsidies, they remain the same as those for the original IBR plan. The DOE will cover all interest for the first 3 years for subsidized loans. For unsubsidized loans, as well as subsidized loans beyond the first 3 years, there is no interest help.

For borrowers who wish to switch out of New IBR, they must enter into a 10-Year Standard plan for at least 1 month or make at least one reduced forbearance payment, which can be negotiated with the loan servicer (and can potentially be very low). Any outstanding, unpaid interest when switching plans will be capitalized.

Calculating the Required Payment for Various Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans – An Example

Given all the variation in rules across IDR plans, required minimum payments can vary significantly depending on the situation. Let’s look at an example.

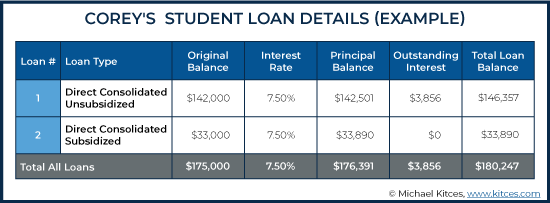

Corey is a young attorney with a current student loan balance consisting of $176,391 principal + $3,856 interest = $180,247 at a 7.5% annual interest rate.

After graduating, Corey could not afford the required payments under the 10-Year Standard Plan and switched to a REPAYE plan. Upon doing so, his outstanding loan interest was capitalized and added to his principal balance.

Corey suspects that REPAYE might not be the best plan for him, and seeks help from his financial advisor to determine what his best course of action would be to manage his loan repayments most effectively.

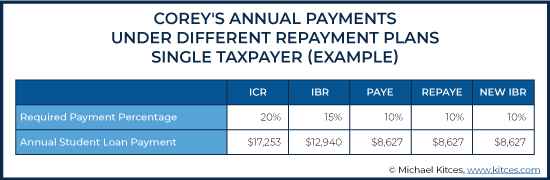

Corey earns an annual salary of $120,000. After his 401(k) contributions and other payroll deductions, his AGI is $105,000. Based on the state in which Corey lives, 150% of his Poverty Line (for a family size of 1) is $18,735, which means his discretionary income is $105,000 – $18,735 = $86,265.

Under Corey’s original 10-Year Standard Repayment plan, Corey was required to make annual payments of $24,924. Under the IDR plans, however, his monthly payments would be significantly lower, with forgiveness of the outstanding balance after 20-25 years.

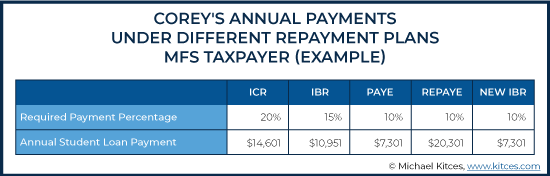

The table below shows Corey’s annual payments for each of the IDR plans:

The range of payments available to Cory across the plans is substantial, more than $8,600 in the first year alone (between $17,253 for ICR and $8,627 for PAYE, REPAYE, and the New IBR plans), assuming that he is eligible for all options, which may not always be the case. Notably, as the plans become more current, they also become more generous with lower payment obligations.

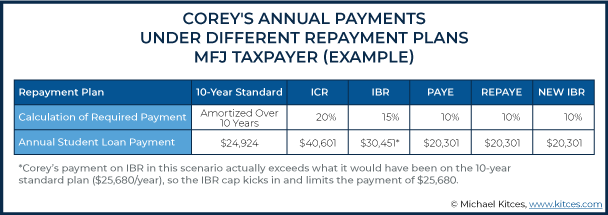

Corey has indicated that he plans to marry and adopt a child in the next year and that his soon-to-be spouse currently has an AGI of $130,000. With the larger income and larger family size, his options are updated as follows, assuming the family will be filing their taxes jointly:

While the gap between IBR and the other options is starting to grow, using MFS as a tax-filing status can reduce his payments for some of the plans even further. If Corey were to use an MFS Status, his options would be as follows:

Here we see where the inability to use MFS with REPAYE can be harmful to someone who is about to get married, as staying on REPAYE would require joint income to be used to calculate discretionary income, resulting in a substantially higher required payment.

While the New IBR option is very appealing, upon checking Corey’s loan records, his advisor discovers that some of his loans originated before 2014, which excludes him from eligibility as borrowers using New IBR may not have any loan balances prior to July 2014.

Thus, payments on IDR plans for Corey will initially range from $7,301 (under PAYE filing MFS) to $40,601 (using ICR filing MFJ) in annual payments. While this would be the expected range for at least the first few years of the repayment plan, life events pertaining to family size, tax filing status, and income levels can come up that may impact Corey’s student loan repayment amounts.

Beware of Negative Amortization

At first glance, it seems clear that Corey should use PAYE and file MFS next year since that would produce the lowest possible monthly payment. But that could have a significant downside since interest accrual will be larger every year than the required payments if he were to choose PAYE. Which plays out into what is known as “negative amortization”, where the principal-and-interest balance amortizes higher as the excess unpaid interest accrues and compounds.

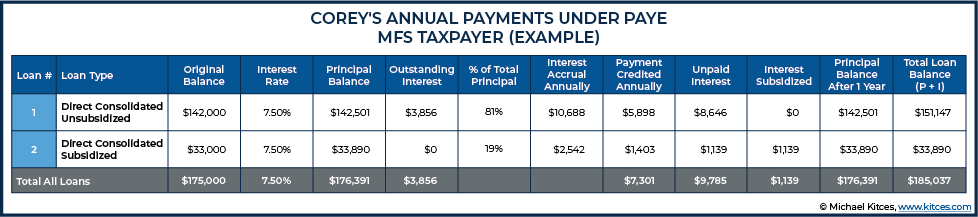

Under normal student loan rules, required payments get split and applied to loans in proportion to the total balance owed. So, in this case, the required payment of $7,301 annually will be applied 81% to the unsubsidized loan, and 19% to the subsidized loan.

If Corey elects to use PAYE and MFS as a tax status, he’ll see his smaller, subsidized student loan principal stay steady in years 1-3 due to the PAYE interest subsidy, but the larger, unsubsidized loan balance will have grown, and his payments of $7,301 this year will have resulted in a balance $4,790 greater than a year ago. Beyond the first 3 years, the interest subsidy is lost, and he’ll see his balance grow for both of the loans.

If his future income growth is low, this plan might make sense, as it would keep his monthly payments low. Using assumptions of 3% income growth and federal poverty level growth, and staying on this exact plan for 20 years, the total principal + interest at forgiveness is $315,395. If we apply a 30% effective tax rate, he will incur just under $95,000 of taxes. If we add the $95,000 of taxes to the $196,000 of payments he made over 20 years, we get to a total loan cost of $290,786.

Corey’s financial advisor compares these numbers to privately refinancing the debt to get a better interest rate. If Corey is approved for a 15-year loan at a 5% interest rate, his monthly payments would be $1,425 with a total loan cost of $256,568. With the help of his advisor, Corey determines that the monthly payment amount under this refinanced loan can be comfortably paid amongst other goals and chooses to pursue the 15-year private refinance option. Under this plan, Corey will pay down the debt sooner (15 years, versus 20 years under PAYE filing MFS until forgiveness) and will pay less in total costs along the way. In addition, he can eliminate the uncertainty (and anxiety) of seeing a constantly growing loan balance, and actually see progress to $0 being made along the way.

Student Loan Repayment Planning for Negative Amortization

Negative amortization isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker. It goes back to whether the intention is to pay off the loan in full, or, to go for some form of forgiveness. In reality, for those who do plan to aim for forgiveness, it actually makes sense for the borrower to do everything they can to minimize AGI, not only resulting in lower student loan payments but also having a higher balance forgiven. This can make sense both for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), where the balance is forgiven after 120 payments (10 years) and is not taxable, and also for a borrower going towards the 20- or 25-year forgiveness available under one of the IDR plans.

I regularly see people who make $50,000 – $70,000 per year with loan balances over $100,000. For a resident physician, who will see their income dramatically rise, an IDR plan (usually PAYE or REPAYE) makes sense to make payments manageable while in residency, even if it means a small amount of negative amortization on their loans. Their ability to repay the loans once they have their full doctor salary means that going for long-term forgiveness rarely makes sense, but the IDR plan can help them manage cash flow during the tight income years as a resident for a relatively modest cost (of negatively amortized interest).

Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans Can Be Advantageous For Earners Expecting Modest Levels of Long-Term Earnings Growth

Many borrowers with early-career income levels similar to a resident may not have the same expectations for substantial long-term earnings growth in their future. For these individuals, pursuing long-term forgiveness using an IDR plan may be a more advantageous option. In other words, negative amortization isn’t just used to incur a small amount of interest to be repaid in the future when income rises, but a potentially larger amount of negatively amortizing interest that will ultimately be forgiven altogether.

Let’s look at another example.

Shannon the Acupuncturist

Shannon is a 28-year-old who runs her own acupuncture business. Other important details about her situation include:

- Total income is around $51,000.

- Her AGI is $37,200 after factoring in SEP IRA contributions, self-employed health insurance deductions, and student loan interest deductions.

- Her discretionary income is $37,200 (AGI) – $18,720 (Federal Poverty Line for her state and family size) = $18,480

- Her current student loan balance is $82,579, and the interest rate on her loans is 5,89%.

- She is single and currently has no plans to marry.

Here are her repayment options:

The 10-Year Standard plan would require her to pay $13,200 annually (over $1,100/month), which is clearly not feasible. She could instead choose to repay with a 25-Year Standard Repayment plan, but Shannon would end up paying nearly $192,000 over that time and the $640 monthly payment would also be infeasible unless she stopped contributing to retirement accounts.

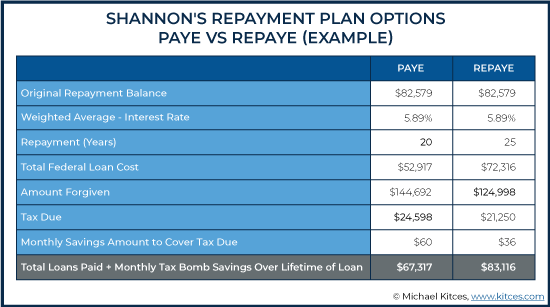

Since she is eligible for PAYE and REPAYE, neither IBR nor ICR makes sense, as each has higher required payments. So, we will decide between PAYE or REPAYE, each of which requires her to pay 10% of her Discretionary Income, or $154 per month at her current income level.

The interest subsidies on REPAYE are better, as while both PAYE and REPAYE will subsidize 100% during the first three years of the plan, REPAYE will continue to subsidize 50% of interest afterward whereas PAYE will not subsidize interest after three years. Thus, the growth of Shannon’s balance due to an increasing interest balance will be limited with REPAYE.

Using PAYE, however, will result in loan forgiveness in 20 years instead of in 25 years under REPAYE.

Either way, the so-called ‘tax bomb’ must also be accounted for, since the forgiven loan balance will be treated as taxable income received in the year the loan is forgiven. Borrowers pursuing any IDR plan should plan to cover that tax, and in this case, Shannon can do so with relatively small monthly contributions to a taxable account.

To sum it all up, to repay her loans in full on a 25-Year Standard Repayment plan, Shannon likely would have to pay $640 per month, at a total repayment cost of $192,000.

On REPAYE, she would start with payments of $154/month based on her Discretionary Income and, factoring for inflation, top out in 25 years at $343/month. She would owe a total repayment amount of $72,316 in loan costs + $21,250 in taxes = $93,566.

If she chooses PAYE, she would have starting payments of $154/month (also rising, to $295 with AGI growth over 20 years), with a total repayment amount of $52,917 in student loan costs + $24,598 in taxes = $77,515. She would also finish in 20 years (versus 25 years on REPAYE).

Assuming all goes as planned, PAYE appears to be the better choice, as even though REPAYE provides more favorable interest subsidies, Shannon’s ability to have the loan forgiven 5 years earlier produces the superior result.

But what if her situation changes, as life does tend to happen that way?

If Shannon got married, and her spouse made substantially more than her, she may have to use MFS to keep her payments lower, and thus lose out on any income tax benefits available filing as MFJ.

Shannon also runs the risk of having to repay a higher balance in the future if she switches careers; in this situation, using PAYE for the 20-year forgiveness benefit would no longer make sense. Say she takes a new job resulting in AGI of $110,000 annually, and she takes that job 5 years into being on the PAYE plan.

Instead of repaying the original balance she had at the outset of opting into the PAYE plan, she would need to pay back an even higher balance due to growth during the years on PAYE, when payments were smaller than interest accrual resulting in negative amortization. As her salary rises, her payments would also rise so substantially (up to $747 here), that her total repayment cost to stay on PAYE for 15 additional years would actually be more than it would be to simply pay the loan off.

If she decides to reverse course and pay off the loan balance instead of waiting for forgiveness, she might instead benefit from a private refinance if she can get a lower interest rate, since that now once again becomes a factor in total repayment costs.

In the end, IDR plans have only been recently introduced, and as such, there is very little historical precedent regarding their efficacy for relieving student loan debt, particularly with respect to the income tax ramifications of student loan debt forgiveness. As in practice, ICR has rarely been used for loan forgiveness (difficult as the percentage-of-income payment thresholds were typically high enough to cause the loan to be repaid before forgiveness anyway), and the other IDR plans have all been rolled out in the past decade.

Accordingly, we won’t see a critical mass of borrowers reaching the end of a 20- or 25-year forgiveness period until around 2032 (PAYE) and 2034 (IBR). And will then have to contend for the first time, en masse, with the tax consequences of such forgiveness. Though forgiven loan amounts are taxable income at the Federal level, it is notable that Minnesota has passed a law excluding the forgiven amount from state taxes.

Similar to other areas of financial planning, it’s prudent to plan under the assumption that current law will remain the same, but also to be cognizant that future legislation may change the impact of taxable forgiveness. By planning for taxation of forgiven student loan debt, advisors can help their clients prepare to pay off a potential tax bomb; if the laws do change to eliminate the ‘tax bomb’, clients will have excess savings in a taxable account to use or invest as they please.

IDR plans are complex but offer many potential benefits to borrowers with Federal student loans. Thus, it is critical for advisors to understand the various rules around each plan to recognize when they might be useful for their clients carrying student debt. The benefits vary significantly, and depending on a borrower’s situation, IDR plans may not even make sense in the first place. But for some, using these plans will offer substantial savings over their lifetimes. Despite the uncertainty surrounding these repayment plans, they remain a crucial tool for planners to consider when assessing both a client’s current-day loan payments and the total cost of their student loan debt over a lifetime.

Leave a Reply