Martin Luther King stayed up til 4am working on his speech for the National Mall on August 28th, 1963. He had both typewritten pages and handwritten pages with crossed out words and rewritten phrases all over the place. He wasn’t exactly sure what the final version would look like, right up until the time he actually delivered it. That day it was a humid 87 degrees in Washington, DC. King spent the morning greeting politicians on Capitol Hill as the crowd assembled for the earlier speakers and gospel singers who would be part of the program.

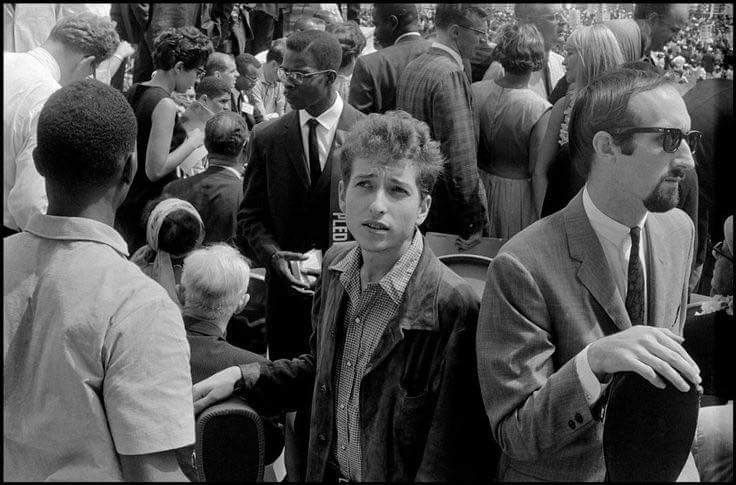

Reporters were buzzing earlier in the day that attendance for the event would fall short of the expected 100,000 people. But then the first Freedom Train pulled into town and the flood gates opened. By the afternoon, a train was arriving at Union Station every five minutes and a bus every 2 minutes. It is estimated that a quarter of a million came to watch Dr. King speak that day. Celebrities like Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, Sammy Davis Jr, Burt Lancaster, James Garner, Bob Dylan, Marlon Brando and King’s close, personal friend Harry Belafonte are among the gathering crowd. President John F. Kennedy watches the speech live on television and is absolutely blown away.

Bob Dylan, age 22, performed songs from his upcoming album “The Times They Are A-Changin’.”

Actors Sydney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and Charlton Heston joined King at the Lincoln Memorial that day

Writer James Baldwin and actor Marlon Brando in attendance

King had used the phrase “I have a dream…” in front of live crowds before, and some of his advisors had urged him to put it aside for this event, as they felt it was a little too quaint or played out. King hadn’t planned on including this section in his remarks that day. As his 15 minute oration was drawing to a close, however, the inspiration to go there took hold and, well, he went there.

The Guardian’s Gary Yonge recounts the spontaneous moment…

A smattering of applause filled a pause more pregnant than most.

“So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.”

“Aw, shit,” Walker said. “He’s using the dream.”

For all King’s careful preparation, the part of the speech that went on to enter the history books was added extemporaneously while he was standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, speaking in full flight to the crowd. “I know that on the eve of his speech it was not in his mind to revisit the dream,” Jones insists.

King had been using the refrain for well over a year. Talking some months later of his decision to include the passage, King said: “I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point. The audience response was wonderful that day… And all of a sudden this thing came to me that… I’d used many times before… ‘I have a dream.’ And I just felt that I wanted to use it here… I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn’t come back to it.”

Although well received that day, it wasn’t immediately obvious that this speech would go on to become as famous and canonical as Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.. But it was the first time most Americans had heard King speak. Its impact and influence would be a slow burn, taking on new gravitas in the wake of the 1968 assassination.

King wasn’t popular at the end of his life. His anti-war stance and alleged communist sympathies left him far outside of the mainstream. Writing at The Nation, Yonge explains:

Perhaps the best way to comprehend how King’s speech is understood today is to consider the radical transformation of attitudes toward the man who delivered it. Before his death, King was well on the way to being a pariah. In 1966, twice as many Americans had an unfavorable opinion of him as a favorable one. Life magazine branded his anti–Vietnam War speech at Riverside Church “demagogic slander” and “a script for Radio Hanoi.”

It wasn’t until 1983 that President Reagan had grudgingly signed Martin Luther King Day into law as a federal holiday.

So what happened?

Time.

But in thirty years he went from ignominy to icon. By 1999, a Gallup poll revealed that King was virtually tied with John F. Kennedy and Albert Einstein as one of the most admired public figures of the twentieth century among Americans. He ranked as more popular than Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Pope John Paul II and Winston Churchill; only Mother Teresa was more cherished. In 2011, a memorial to King was unveiled on the National Mall, featuring a thirty-foot-high statue sited on four acres of prime cultural real estate. Ninety-one percent of Americans (including 89 percent of whites) approved.

As the Dream became a reality in towns and cities across America, its prescience began to seem obvious in hindsight. Of course we should have a society where black and white children grow up together in mutual respect and harmony. Of course America ought to arrive at the full realization of its original promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for all citizens. One of those self-evident truths that Thomas Jefferson had written about – even if only narrowly conceived in the context of the times he lived in. King’s vision had slowly but surely become reality over the decades since he had shared it with us in 1963.

Below you can watch him deliver his now famous speech to the masses that day. It hasn’t lost even one ounce of its power and majesty almost 60 years later.

Further reading:

Martin Luther King: the story behind his ‘I have a dream’ speech (The Guardian)

The Misremembering of ‘I Have a Dream’ (The Nation)

4 Little-Known Reasons Martin Luther King Was An Amazing Leader, Human (Fast Company)

Leave a Reply