Executive Summary

In these stressful times, as we deal with fears arising from the coronavirus pandemic and market volatility, many financial advisors are being inundated by scared and panicking clients worried about how their assets (and financial goals and futures) will fare. And while advisors have a responsibility to try to calm their clients and talk them off the ledge of these scary market conditions, advisors have their own health and emotional well-being to care for, as well. Because in times like these, clients who are worried about the resources that advisors may be managing for them often take their fear and anxiety out on their advisor, despite the advisor’s best efforts and intentions to help them weather the storm. And for advisors who deal with fearful, stressed-out clients day after day, meeting after meeting, the emotional toll that they experience can itself be traumatizing and, without taking time for self-care, can have serious adverse effects on the advisor’s own physical and emotional well-being.

As while clients may experience stress from painful events they experience directly (i.e., “Direct” trauma-related stress), advisors are more prone to “Indirect” trauma-related stress when dealing with so many of the same client fears and concerns (not to mention the direct trauma-related stress of what the market decline may be doing to the advisor’s own business). After all, when advisors take on one fearful client conversation after another, it’s often difficult not to start internalizing their clients’ concerns, whether in the form of “vicarious traumatization” (when the advisor begins to identify with the client’s concerns personally as if those concerns were actually their own), or through “compassion fatigue” (when the advisor begins to personally experience the emotional pain and suffering that they perceive the client is actually experiencing).

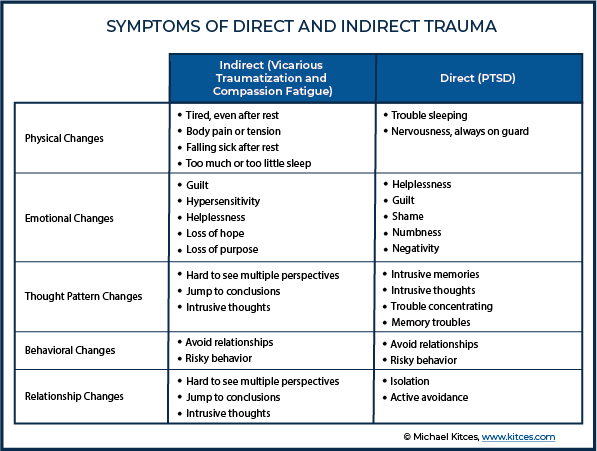

And unless the stress is somehow dealt with, a range of adverse symptoms can result – from physical changes to emotional, behavioral, and relationship changes. On top of being harmful to the advisor themselves, this stress can also have an adverse effect on the client relationship, because if left untreated, prolonged stress can result in an individual isolating themselves to avoid relationships (and the stress they’re inducing). Which in turn can halt the communication process between the advisor and client, ultimately leading to the client straying from their financial plan and even leaving the advisor altogether.

An effective remedy to cope with traumatic stressors is to practice self-care through self-compassion, which is a person’s ability to comfort and soothe themselves. Research has shown that self-compassion, unlike self-esteem, has been a key factor for individuals to motivate themselves through pain, failure, and feelings of inadequacy. Some simple suggestions to practice self-care include protecting personal time and setting hard boundaries on when to start and stop work, to communicate those time boundaries to others, and to create short ‘white space’ breaks throughout the day to mentally recharge. Additionally, meeting with clients outside the office can create a change of scenery and avoid an environment (e.g., the advisor’s office) that might trigger a stressful response, reducing (or stopping) the amount of news watched or listened to, and working collaboratively with a partner or in teams to share the load of client meetings that may be potentially emotionally charged.

Ultimately, the key point is that for financial advisors whose clients are currently experiencing high levels of fear and anxiety due to the current market environment, the stress of dealing with those traumatized clients can elicit severe trauma-related stress for advisors, and the symptoms of that stress, without proper care, can ultimately compromise the advisor’s ability to communicate effectively with their clients. Accordingly, advisors should practice self-care and self-compassion so that they can continue helping their clients stay the course of their financial plans, and without themselves suffering from the adverse effects of vicarious traumatization or compassion fatigue.

Financial Loss Can Trigger Stressful And Traumatic Personal Loss

Money and finances can be emotional triggers because of what we believe they say about who we are: I have worked hard to save, and therefore, I am a responsible person; I have saved enough to retire, and therefore I had a successful career; I have taught my clients about market volatility, I offer a valued perspective and relationship to my clients. So, when the market falls sharply and individuals experience loss, even though the advisor explains that the loss is typically short-term and their portfolio has been built to withstand market turmoil, the loss itself can still hurt (especially since portfolio losses often do not feel ‘fair’) and feel intensely personal.

In other words, even if a client understands that the loss may be ‘temporary’, this will not necessarily shield them from feeling a wide range of emotional stresses and anxieties in the moment that are associated with the loss of the important goals, achievements, and possibilities that the money stood for in the first place (e.g., hard work, freedom, competence, retirement, college, or any other financial goal or financially based, self-image imaginable), especially when those losses feel ‘unfairly’ inflicted upon them and are beyond their control.

Example 1: Jerry is a younger, newer client and has been saving diligently for the past five years with his advisor. The coronavirus marks the first time that Jerry has really experienced frightening market turbulence.

Jerry tells his advisor that intellectually, he understands what is expected, and he understands the mathematics around what is happening; he even appreciates this as an opportunity to rebalance and buy more stocks at lower prices.

Yet, Jerry also tells his advisor that he cannot kick the sick emotional feelings of loss and grief in the pit of his stomach, knowing that 5 years’ worth of his hard work savings, $25,000, just disappeared in 24 hours.

Stress Emerges In Different Forms And Results From A Variety of Triggers

Especially in times of high market volatility, it is important to stress that, even though market conditions impact clients’ portfolios in nearly universal ways and that most everyone is experiencing some material short-term loss, clients themselves are impacted in very unique and personal ways. And it’s those personal connections between their money, their goals, and their own sense of success and accomplishment – and how they are threatened in a bear market – that tend to trigger clients to call in the first place. Or stated more simply, anxiety in a bear market often isn’t so much about just the lost money itself; it is more about what the money represents and personally means (and may feel lost) to the client.

And the grief caused by loss isn’t the only type of stress or anxiety they may feel. They may also experience nervous anxiety and pressure to sell their investments. They may have fear induced by what they see on the news and in the behavior of others around them – it is very unsettling to walk into the neighborhood Target or local grocery store only to be faced with barren shelves and customers fighting over hand-sanitizer and toilet paper!

There is also the disappointing distress of having to change plans that they really, really wanted to make happen.

Example 2: Lydia is a long-time client and appreciates the work of her financial advisor. Yet the media, frightening news headlines, and TV chatter about the market “crashing”, has her spooked.

She has been putting off calling her financial advisor because she does not want to be “that client” – she successfully weathered the 2008 crash, and she believes that she shouldn’t be feeling stressed by the current market conditions. She assumes that her financial advisor is just going to tell her to “weather the storm” and simply to consider making temporary spending cutbacks.

After a week of trying to talk herself down, though, she finally decides to call her advisor. She knows all of the “answers” she’ll probably hear from the advisor, but nevertheless, she is feeling hopeless, frazzled, and wants some feedback about the situation.

She just wants to retire, as previously planned, so she can spend more time with her grandkids – she thinks, how will this loss of $250,000 really impact my plans? As while she likely can weather the pullback and temporary cutbacks, the thought of having spent so long saving and now facing less time and opportunity to visit the grandkids still grieves her.

For clients who are business owners (or for advisors who, themselves, are business owners), extreme market volatility can be especially mentally stressing, and even perceived as a direct personal attack, as it is the marketplace that ultimately governs a business’ capacity for staffing employees and its ability to serve the public.

For example, while business owners may personally be okay or able to ride out the storm during an economic downturn, the slow pace of business may force them to let employees go to keep the business afloat, and that burden of being responsible for the lives and livelihood of others can weigh very heavily on the business owner’s shoulders. In a service business in particular – like that of a financial advisor – owners also have the additional stress of worrying about what may happen to their clients or customers if the business has to cut back on hours or staff or even close its doors altogether.

Finally, when it comes to market volatility and all of the personal stress that can be associated with economic uncertainty, it is important to recognize that an individual’s ability to communicate and think may likely be characterized by aggressiveness and tunnel vision. In other words, when money feels tight or scarce, there’s a good chance that there will be more fighting and less of an ability to see the bigger picture.

Example 3: Tammy and Frank have decided to visit their financial planner for reassurance surrounding their plans for a 2021 retirement.

Yet, even before really sitting down Frank says quite sternly to their financial planner, “I don’t want to hear that this is expected or that I just need to weather the storm; I only want to hear that I can retire!”

Tammy chimes in, “Yeah, we need actual answers – we do not want to be placated today; we have to retire, and I do not want to talk about anything else.”

Tammy and Frank are ready to fight.

Why the hostility and why the focus? Simply put, it is human nature. First of all, fighting is a natural response to stress (with other natural responses that include fleeing, freezing, or flocking). Second, money is a thing people tend to stress a lot about – whether the stress is caused by consumer debt, retirement savings, or just the high cost of living, money causes people to worry not just about achieving big goals, but also simply to maintain their self-sufficiency and means for survival. And third, when resources are scarce, our brains tend to focus.

Research by Dr. Sarah Asebedo and Emily Purdon, published by the Financial Planning Association, shows how conflict theory can be used as a way to organize and prepare for communication around money. Their research points out that money fits within this theory well because it is scarce, represents a distribution of power, can promote competition, and is often seen as primary to self-preservation. In Example 3, Tammy and Frank are not really gearing up to fight because they are angry about their retirement assets but, instead, they are ready to fight because they are worried about their self-preservation (and the advisor has ‘coincidentally’ ended out putting themselves on the opposing side of the table while they’re in “fight mode”).

Moreover, even though their behavior might appear irrational, seen from this perspective of self-preservation, Tammy and Frank can actually be understood to have perfectly rational behavior. Tammy and Frank are also rational if we view their behavior through a scarcity lens. When the mind encounters a situation in which resources essential for survival are scarce, hyper-focus on those resources is completely natural and understandable, as it would behoove the individual to pay extra attention to those scarce resources as a means of self-preservation.

As if all of these considerations were not enough when thinking about clients and their ability (or not) to clearly articulate their experience and underlying fears, there is also the important consideration of how stress puts an individual at risk for trauma-related emotional distress, which is likely the most impactful and paramount to actually understanding and being able to help clients (and advisors, themselves) during these tumultuous times.

What Does Emotional Trauma Really Mean?

Yet before jumping into the different types of trauma-related emotional distress and what they entail, let’s define what “trauma” actually means and be very clear that, yes, someone really can have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)-level trauma from market decline (and is not just being melodramatic).

When we hear the word “trauma”, it is normal to think of really, really awful things. And yes, really, really awful things are traumatic. And because trauma is typically associated with really, really awful things, we tend to think in comparative statements about our exposure to potentially-traumatic events. We might think “Losing $25,000 is not as traumatizing as losing $250,000.”

However, even though trauma can be discussed in terms of relative magnitude, on an individual basis, magnitude flies out the window. Remember Jerry and Lydia from Examples 1 and 2 above? While Jerry may not have lost as much as Lydia, does that mean Jerry should hurt less than Lydia? Absolutely not. Because Jerry’s $25,000 loss was still an extremely meaningful (and potentially traumatic amount) to Jerry, even if the loss is far less than what Lydia lost (or what the advisor’s other clients have lost).

And the ‘why’ or ‘how’ of the fact that the magnitude of the loss doesn’t matter is obvious – Jerry and Lydia do not really care about the money, per se; Jerry and Lydia care about what the money represents to them (i.e., their ability to retire, or their years of hard savings and frugal lifestyle “wasted”). Jerry’s hard work has been washed away and has left him feeling cut off at the knees. For years, he saved and did everything right and yet, overnight, all his work is gone. That is traumatic. Lydia has stuck with her financial advisor and followed her plan; does sticking by her financial plan again, now updated after the drop her portfolio has suffered, mean she must now choose between her retirement and her grandchildren? Facing that decision is traumatic.

Moreover, anyone and everyone can experience trauma, and it isn’t a competition about who has it worse. If it hurts, it hurts.

Financial Stress Can Elicit Both ‘Direct’ and ‘Indirect’ Trauma-Related Stress

Just like other types of stress, financial stress can and does put everyone at risk for trauma-related emotional distress. There are essentially two types of trauma-related stress that can generally be referred to as ‘Direct’ and ‘Indirect’. Both types of stress can be bad, as they each pose challenges to the client-advisor relationship.

A ‘Direct’ trauma-related stress is when a person is actually involved in the traumatic event. Jerry, Lydia, Tammy, and Frank all felt directly involved in the market decline. And you may be thinking, well, aren’t we ALL involved in the market decline? And the answer would be yes, but this goes back to the question of magnitude. Some clients are not going to be as upset about their decline and, if they are not upset – per the standard definition of stress (where stress is a 2-part process in which a person first recognizes the event as a threat, and then decides whether they can handle it) – are they really suffering from stress? Moreover, some clients may be relatively unphased and simply not view the turbulence as a direct threat (at least for now).

A well-known example of direct, trauma-related stress is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD can occur when someone personally experiences a traumatic event that is severely distressing to them (although PTSD can also be developed indirectly, such as via the news).

In the case of financial planning clients, it is important to note that when it comes to money, PTSD does lurk in a few corners. For example, research by Audrey Freshman in 2012 found that individuals who had been impacted by Ponzi schemes exhibited symptoms of PTSD. Dr. Goulston on Psychology Today has written about PTSD and its connection with debt. Researcher and financial-therapy practitioner, Dr. Maggie Baker, has reported working with multiple clients that have exhibited signs of PTSD after the market crash and turmoil of 2008-2010. And even when it comes to financial advisors, PTSD can be a real issue as well – a study by Dr. Brad Klontz and Dr. Sonya Lutter found that 93% of advisors who were interviewed reported medium to high levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

The second type of trauma-related stress is ‘Indirect’, which can show up in a couple of varieties: vicarious traumatization, and compassion fatigue. With vicarious traumatization, a mental health provider or caregiver (or financial planner!) will actually develop or take on their client’s trauma after repeated exposure, leading to a profound (and negative) transformation of the professional’s own inner experience. With compassion fatigue, the mental health provider or caregiver (or financial planner!) empathizes with the client so completely that, at a subconscious level, the professional’s brain is actually triggered as though they themselves are experiencing pain.

As seen in the chart below, direct and indirect trauma look a lot alike and can bring about many of the same symptoms – which is not good if you are a financial advisor (at risk for indirect vicarious trauma or compassion fatigue) working with lots of clients (experiencing direct trauma-related stress), especially while the advisor’s own business goes through its own financial turmoil (another form of direct stress). And stress symptoms of trauma that each type may generate (i.e., the financial advisor’s indirect or direct stress alongside the client’s direct stress), can easily result in the breakdown of communication ad the ability (for both the client and the advisor!) to talk about and work through the conditions and events resulting in the stress in the first place.

In other words, trauma often leads people to pull away, isolate, or even engage in potentially dangerous or self-destructive behavior, which is not what advisors want their clients to do. Furthermore, most financial advisors do not receive training in dealing with victims of trauma and the effects of indirect trauma (as opposed to mental health professionals, where it is a standard aspect of the training), leaving them even more prone to the negative effects of indirect trauma themselves as well.

And for those who may still question whether or not that stress arising from money and finances is a real concern, consider the statistics from both a study by Bob Veres and the findings of the study from Klontz and Lutter – both studies found that a large majority of financial planners switched their buy-and-hold investment strategies to more active strategies after the 2008-2010 recession. Financial advisors, and by default their clients, engaged in different (and potentially riskier) behavior – a hallmark of behavioral changes observed in victims of direct trauma (i.e., PTSD), and indirect trauma (i.e., vicarious traumatization and compassion fatigue).

Focus on Self-Compassion (and Not Self-Esteem) As An Effective Trauma-Recovery Tool

Many traditional financial planning clients (and their advisors!), tend to be high achievers, which raises a potentially critical issue about resiliency and what people use to retain a positive image of their self-worth – self-compassion and self-esteem – in the face of setbacks (like the severe and high-impact market declines that no one can predict or control).

Spoiler alert: trying to maintain and lift your self-esteem is actually not going to help.

Example 4: Charles is an exceptionally savvy business owner and has always prided himself on his success. He has worked closely with his financial advisor over the years, and actively participates in his portfolio decisions.

Charles feels that much of the portfolio’s past success is, in large part, a reflection of the work and ideas he contributed himself (in addition to those of his financial planner).

Yet Charles, like everyone else, did not predict the impact of the coronavirus. In reaction to the news and market activity, he bought and sold different positions without alerting his financial advisor, because he was “sure” he knew what to do. Yet, in the days following his transactions, his portfolio, unfortunately, plummeted even further in value.

When Charles finally picks up the phone to call his financial advisor, Charles is reeling from self-doubt and struggling with his own personal trauma that has arisen from his fractured self-image as a “savvy business owner”; instead, he now he sees himself as a failure when his investment efforts, for the first time ever, did not yield the success he anticipated.

To understand this idea more fully, it is helpful to start with what self-esteem is and how it works. First, self-esteem is an assessment of self-worth, but one that involves subjective judgment (e.g., Charles thought he was a good businessman), is often comparison-based (e.g., Charles thought he was a good businessman because he had performed better than other investors after making trades in his portfolio)… and can be fleeting.

Basically, in order to have high self-esteem, it follows that at some level an individual believes they are better than other individuals in their peer group (or some other relevant comparison group). For Charles, once his business acumen failed him and he felt he was floundering in the market doing worse than other investors, Charles was no longer convinced that he was any better than the average investor. This personal loss, the loss of pride and, for Charles, the lost belief that he was better than the average investor, can be very painful.

Notably, financial advisors are not immune to this either. In fact, advisors are typically trained to believe that they have the “right” answers for their clients (thus why clients pay for us for our expertise!?), and in many instances, pride themselves on being able to solve clients’ problems.

Yet, when the market plummets, there is nothing advisors can do to really fix the problem. There may be opportunities to rebalance and talk about market corrections, but advisors cannot just make a 20% drop in a client’s portfolio go back up so the losses (and the client pain) go away. Moreover, for financial planners who are driven by self-esteem (and it is totally normal to be driven by self-esteem!), this volatile market is going to be hard on them, too, because there may be times they feel like they are failing their clients.

One last important concept that can crop up during meetings with traumatized clients is countertransference. Countertransference is a therapy term that describes when the mental health practitioner (or financial advisor!) over-identifies with the client and through over-identification loses their ability to be objective. Said another way, the issue with countertransference is that the advice given to the client may not really reflect the needs of the client, but instead the needs of the professional. What is more, if the mental health provider (or the financial advisor!) starts to see themselves in the client the mental health practitioner (or the financial advisor!) may even become blocked and unable to provide new solutions to the client because they themselves, the professional, are too flooded with emotion.

Now, you might be thinking, “Geez, countertransference sounds a lot like empathy… and isn’t empathy supposed to be a good thing?” And the answer to that question is, yes, empathy is good, but countertransference is not. Countertransference is an over-empathetic reaction and it can negatively impact the advice given to clients, as well as the communication in the client-professional relationship.

Example 5: Candace is a new client and has only been working with Penny, her financial advisor, for a short time. Candace has come in today to talk to about what has been going on in the market and how to move forward.

During their discussion, Penny really starts to identify with many of the life experiences and emotions that Candace is sharing. Candace is feeling nervous. And Penny also begins to feel nervous – how could she not? She has sat through 15 of these meetings in the past week, and thanks to vicarious traumatization, Penny is as freaked out and just as tired as Candace is.

At one point, Penny does not even ask Candace to “tell her more”; instead, Penny assumes (incorrectly) that Candace is just like her and ends up giving her advice that she would have wanted to hear… but not necessarily what Candace needed to hear.

Moreover, even though empathy is generally a great quality to practice with clients, it can also have a dark side. Because if the mental health practitioner (or financial advisor!) is too empathetic for too long without properly resting (or does not have the requisite training to handle it), it can lead to indirect trauma. In some ways, countertransference is a culmination of stress, trauma, and the drive for self-esteem all mixed together, and is something that commonly happens in professional-client relationships.

But now for some good news! Self-compassion, instead of self-esteem, offers a better way forward, because it isn’t about judgment (am I worthy of ‘esteem’ or not?), and it is not contingent on surpassing any other group or individual.

Self-compassion is a person’s ability or capacity to comfort and soothe themselves. It is also key to motivating oneself through pain, failure, or feeling inadequate. What is more, the research is crystal clear that self-compassion is really important to self-care and the ability to rebound through stressful, traumatic setbacks. Self-compassion has been linked to higher levels of optimism, curiosity, and initiative, and, at the same time, associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression.

Self-Care Isn’t Selfish And Can Be Easily Practiced (And Most Effective) With Self-Compassion

There is a reason why flight attendants tell plane passengers that, in the event of an emergency, they must first put their own oxygen mask on before helping another person with their mask – people can’t help others if they have not yet helped themselves first.

For financial planners reading this blog – this means you!

The path to better communication, leading away from trauma and burnout, starts with you.

The good news is, again, that we can lean on research from Dr. Kristin Neff on self-compassion and modify actual, research-based programs used by mental health practitioners to bolster resiliency for answers. They have been aware of this countertransference problem for a long time (they too can feel like failures when their clients do not improve, or they do not know what to do to “fix” their client) and have identified self-compassion as a better way forward; you and your clients can, too!

Practical Suggestions for Financial Advisors To Manage Bear Market Stress And Trauma

Financial planners can cultivate self-care in a variety of ways, but a key theme is making time for personal care. If you read nothing further, please know that learning to protect your time is of utmost importance. As Carl Richard’s said in a recent Kitces and Carl episode on how to build resilience as a financial advisor, “time for yourself is [and should be] a prerequisite, not a reward.”

And this may be even more important for many financial planners who, in the wake of the coronavirus, are actually working from home where the temptation to work around the clock is huge because… the work computer is now right there.

The following tips are suggestions on how to protect your time for your own self-care:

- Have a designated stop time. Today, at this very moment, financial planners who are reading this blog are challenged to decide – and then follow through – to set work down at 7:30pm this evening and not look at it until tomorrow at 7:30am (or whatever times you will set from when you ‘wrap up’ at the end of the day, until you get up and get in front of your computer to work tomorrow).

For employees, this means not taking work laptops to bed or to the couch. Leave them in designated workspaces, and stay out of that area after 7:30 pm. This also means not responding to emails after hours! Do not read emails. Do not scan the titles of emails. You’re not going to solve a major problem late in the evening. It will be there to solve tomorrow morning. Instead, at your set downtime, simply leave your work in a different room, and rest or recharge in the way that best serves you.

For employers, this also means not emailing employees or calling them after work hours. Let your employees have their downtime.

- Indicate stop and start times to others. Mark the start and stop times just committed to above, and indicate to co-workers when that downtime starts and stops. Doing so helps others know when it may or may not be okay to contact you. And may even help bolster the dedication to starting and stopping on time by actually putting those times in calendars that are shared with others.

- Create white space. Holding meeting after meeting and phone call after phone call is exhausting; it can very easily put a person in a reactionary mindset, let alone take an inordinate amount of time, and possibly lead to indirect traumatization. As humans, we are simply not meant to hear sad and angry stories one after another – our minds and bodies will begin to take on that stress and pain. With this burden of vicarious traumatization, financial advisors will not be able to give their best to their clients, even if they wanted to.

Accordingly, the risk of indirect trauma can be mitigated by simply scheduling 15-minute breaks between all meetings, and rescheduling meetings where necessary (and possible). When it is not possible to reschedule meetings, Carl Richard’s suggests that advisors ask clients to wait a few minutes on hold while the advisor “grabs their folder”. Even if the advisor may not really need to grab anything, it does give the advisor (and client) the opportunity to have a moment to reset and mentally prepare for the ensuing conversation.

Resetting can include any quick activity that helps the advisor clear their mind, such as taking a walk (even if it’s just down the hall to get the “folder”), getting a glass of water, stretching, taking some deep breaths, moving away from your laptop to look outside, or enjoying your lunch (not sitting in front of your computer screen!).

- Hold a webinar. Another time-saving strategy for advisors is to announce a virtual webinar for all clients to talk about what is going on in the markets, instead of spending time reaching out to clients individually (which won’t sound weird in light of social distancing!). The one-to-many communication channel can be more time-efficient to deliver the message, and may help to buffer the advisor from some of the client conversations (if clients “just” needed information and can get it from the webinar, it saves what can still turn out in the moment to be a stressful conversation if the client gets an additional opportunity for one-on-one venting).

- Let it out. Aside from time, another important thing to remember is that you are not a punching bag! And you are not invincible. Moreover, it is okay and normal if you are scared, and it is okay and normal if you are having difficult time. This is scary. This is hard. As such, talk with your fellow advisors, talk with your friends and family. Use this time to reconnect (or get connected). Do not allow yourself to fall into total isolation where the only people you are speaking with are upset clients.

Practical Suggestions for Advisor-Client Meetings And Support

Downtime is important for everyone. While financial advisors can encourage clients to stop their work early and practice healthy boundaries between their work life and personal life, here are some other ideas for clients and advisors:

- Get out of the office. With all of the social distancing going on, this might be easier or already happening. But if advisors do need to meet with their clients in person, try meeting outside of the office. Just going to the office can trigger stress, as the client knows why they are going there, and may even have memories from 2008-2009, the last time they had to sit in front of their financial advisor to talk about a crash. A change of scenery can help to ease nerves.

- Stop watching the news. Just like financial advisors can take on stress from listening to their clients, both clients and advisors can take on stress just by listening to or watching the news over and over again. Clients and advisors need downtime away from the negative and scary stories. Turn off the TV. Turn off the social media news feed.

- Use the buddy system for two-advisor client meetings. Connecting and social relationships are crucial in times of stress, and advisors typically spend the most time with clients when helping them navigate difficult times. But, it is really easy to over-connect with clients as well… especially when connecting with them is crucial for trust and maintaining an ongoing relationship. Working in advisor teams – where there are always two advisors in every client meeting – may help keep advisors from over-connecting, and thus risking compassion fatigue or vicarious traumatization with their clients. It can also help to develop additional “solutions” and discussion points. After meetings, financial advisors can check in with one another to ensure they are doing okay and not becoming too exhausted, or, as mentioned above, missing a larger issue because they stopped asking effective questions after over-connecting with the client.

Practical Suggestions To Offer Clients

Last, but certainly not least, the tenets of mindfulness and self-compassion make for great suggestions to offer clients (and advisors who want a few ideas for self-care that they can use during all of their white space and downtime) that will help them build resiliency during times of uncertainty and fear.

According to the American Psychological Association, mindfulness is a “moment-to-moment awareness of one’s experience without judgment.” Encourage clients to focus their attention on the physicality of the feelings they may be experiencing, and to normalize what they observe. The goal here is not to tell the client “Don’t be afraid”; the goal is for them to acknowledge their own fear, normalize it, and identify its root. Because it is not typically just the money that is the problem; it is what the money represents to the client. Moreover, encouraging clients to be mindful and aware of how they are feeling not only helps them to cope with those feelings, but helps their financial advisor know specifically what they are dealing with and find ways to help.

Example 6: Jerry said that he felt sick to his stomach at the thought that his hard work had gone down the drain.

Jerry’s financial advisor, who understands the power of mindfulness and how important it is to normalize these feelings, responds:

Jerry, thank you for sharing with me what you are going through. I hear you when you say that your hard work feels like it is all for nothing, and I think what you are feeling is awful, but totally normal.

Loss, when we work so hard for something, is unsettling. However, I also want you to know that I see how hard you are working now.

It was probably not easy to make this phone call and over the next few weeks, or maybe even longer, it will be hard to want to stick to the financial plan. Moreover, I want you to know that you can reach out to me; I want to hear from you if you start to have concerns.

What you are feeling, as awful as it is, is totally normal and rational, so please call and we can talk about it.

As described above, self-compassion is really about soothing one’s self and being able to move forward, in spite of fear or failure.

Financial advisors can help clients to cultivate self-compassion by focusing on two considerations: 1) what the client cares about, and 2) what the client can actually control.

Example 7: Charles, the savvy business advisor, has come to his financial advisor and rather shamefully admits that he has made trades without telling his financial advisor.

Luckily though, Charles’ financial advisor knows the difference between self-esteem and self-compassion, and helps Charles to redirect the feelings that have bruised his self-esteem. Instead of being mad at Charles, the advisor normalizes Charles’ activity, letting him know that it is normal to try to take extraordinary actions in an effort to protect our self-worth.

The financial advisor then asks Charles about where he is now, and what matters most to him today. Charles tells his advisor he is really concerned about his employees; he had to let people go in 2008, and does not want to do that again.

Discussing his underlying fears, Charles and his advisor brainstorm ideas for how he can support his employees during this time and leave his portfolio alone.

Moreover, as a reiteration of what was discussed on our recent webinar, “Calming Anxious Clients About Coronavirus: Tools, Talking Points, & Tips”, when walking clients through these difficult conversations, advisors can ‘bookend’ the conversation with goals, and an appeal to what really, actually matters to the client.

In the case of Charles, it was obvious he wanted to do something to address the situation. His advisor was able to redirect the feelings of needing to do something to behaviors that are not only non-damaging, but also that proactively speak to Charles’ deeper need – protecting his identity as a good businessman who cares about his employees.

As we face the surmounting importance of “social distancing” during the coronavirus pandemic, there are two important considerations to make in order to avoid overwhelming feelings of isolation during quarantine periods.

First, as isolating as it physically is, we are together in spirit. Despite being in quarantine, people are inherently part of the greater, collective good. These quarantine periods are serving to tamp down the spread and growth of the coronanvirus – and each individual is a valued member of that effort.

Second, be social where you can. Be with your family (especially after you stop work for the day at 7:30pm or your time of choice after a long day), use your social networks (but maybe not your scary-news-ridden social media platforms!), and call your mom (or other adults, long-lost loves, and siblings). It is not often that we really get to need each other, so take advantage of the opportunity and do it. Need and love the people around you. As mentioned above, an often overlooked response to stress is to flock (not just fight, flight, and freeze). And so when we experience pain, suffering, setback, and trauma, we can greatly improve our health and our mental state by connecting with those around us.

Leave a Reply