Executive Summary

From February 20th through February 22nd, the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning hosted its third annual Academic Research Colloquium (ARC) for Financial Planning and Related Disciplines in Arlington, VA, to share and discuss research relevant to the financial planning profession.

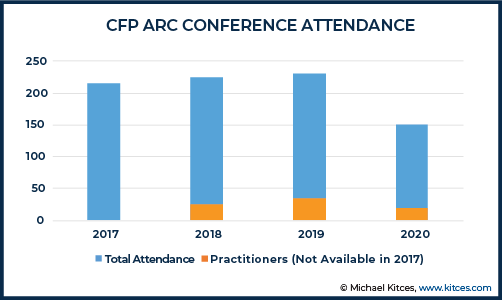

This year’s event saw a sharp decline in attendance, down about 35% from 2019 (150 attendees in 2020, of which about 20 were practitioners), likely attributable to the fact this year’s ARC was held separately from the CFP Board’s Registered Programs Conference (RPC), which is required to be attended by program directors of CFP-registered financial planning education programs. While this decline was unfortunate and definitely impacted the overall atmosphere (fewer practitioners, students, and academics who emphasize teaching were in attendance), the quality of the research remained high, and there were a number of papers presented that had strong implications for financial planners.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – lead researcher at Kitces.com and an assistant professor of finance at the University of Southern Maine – provides a recap of the 2020 CFP Academic Research Colloquium, and highlights a few particular research studies with relevant takeaways for financial planning practitioners.

The 2020 CFP Academic Research Colloquium again had a strong showing from CFP Board Registered Ph.D. programs, with scholars from Missouri, Texas Tech, Georgia, and Kansas State producing nearly 37% of all research (when weighted by type of presentation and authorship rank). Additionally, Ohio State, Alabama, and Morningstar contributed another combined 15% of total research. Despite the concentration among top institutions, the ARC event remains academically diverse, drawing in scholars to present research from a total of 44 different institutions, including Princeton, Carnegie Mellon, and NYU.

This year’s colloquium featured a wide breadth of topics. Some particularly relevant topics for practitioners included:

- A re-examination of the conventional wisdom that small defined-contribution-plan investment menus are better than large menus (instead, research has suggested that bigger menus actually can be better for participants);

- An analysis of U.S. consumers’ willingness to pay for hourly financial planning services (which found that most consumers aren’t willing to pay anywhere near the rates that advisors charge);

- An investigation of whether fintech mobile application nudges can help individuals reduce their spending (yes, they can, but not by very much, and those nudges may drive consumers away from the apps in the future);

- A study examining whether use of a financial advisor among high-investable-asset households is associated with a reduction in financial anxiety or an increase in investment confidence (no to reducing anxiety; yes to increasing confidence); and

- A study exploring whether different types of advisors (advisors at broker-dealers vs. RIAs, CFP professionals vs. non-CFP professionals, etc.) perceive the new “Best Interest” standard differently than a fiduciary standard (yes, they do; advisors at RIAs are more likely to be mistaken or confused about whether Reg B.I. applies to them, although brokers are more likely to mistakenly equivocate the “best interests” and fiduciary standards).

Overall, the fourth Academic Research Colloquium again delivered on bringing together scholars to share high-quality financial planning research. However, this year’s low attendance felt like a step backward for the Center for Financial Planning’s goal to make the ARC the “academic home” of financial planning. Nonetheless, the ARC continues to be a conference worthy of attending for both academics and practitioners who wish to engage in academic research.

From February 20th through February 22nd, the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning hosted its fourth annual Academic Research Colloquium (ARC) in Arlington, VA. The event saw a 35% decrease in attendance, bringing together 150 attendees, of which roughly 20 were practitioners, to share and discuss research relevant to the financial planning profession.

The CFP Academic Research Colloquium is part of a longer-term goal to establish the CFP Board Center for Financial Planning as the “academic home” for the profession. However, the large decrease in attendance this year felt like a minor step back away from that goal. To be clear, the quality of the research presented was still high, and arguably even a continued trend upward despite an attendance set back, but the smaller number of attendees definitely changed the feel of the conference.

This drop-off was likely the result of breaking from prior years’ tradition of holding the CFP Board Registered Programs Conference (RPC) in conjunction with the ARC (the RPC was previously held with some overlap immediately following the ARC). The unfortunate reality for academics on tight budgets is that many universities will not provide funding for multiple trips.

The scheduling of the RPC on March 16-17, 2020 (which was postponed due to coronavirus and a reschedule date has not yet been announced) forced many attendees to choose one conference or the other, and since the RPC is mandatory for registered program directors of CFP-registered financial planning education programs, many professors—particularly those at smaller and less well-funded programs—were only able to plan on attending the RPC.

While the logic for breaking these conferences apart is not clear, the hope is for the CFP Board to bring these conferences back together in the future. In addition to the many folks who might want to attend all or part of the two conferences in one trip (and can afford to do so with their university or firm travel/conference budgets), the atmosphere felt diminished by the move to separate these conferences.

While it is understandable that fewer students attended this year’s ARC event compared to past years, given that the RPC does offer more content geared to students (including a dedicated student track), this decrease is still an unfortunate missed opportunity for students, especially those who may not realize yet what is involved in academic research, to be exposed to the academic side of financial planning.

Additionally, there were fewer practitioners and more teaching-focused academics in attendance, which limits some great opportunities for discussion and networking at the conference.

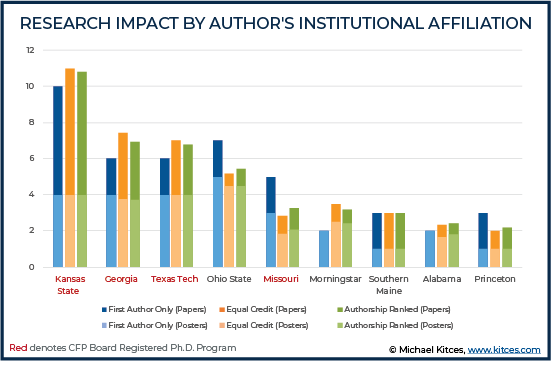

Consistent with the 2017, 2018, and 2019 ARCs, there was a strong showing among some core academic financial planning programs. Not surprisingly, the four universities with CFP Board Registered Ph.D. programs—Kansas State University, University of Georgia, Texas Tech University, and University of Missouri—were among the leaders of universities in terms of papers accepted for an oral or poster presentation.

Other notable attendees included programs with an emphasis on financial planning (although not a CFP Board Registered Ph.D. program) such as Ohio State University and University of Alabama, as well as institutions that put out a lot of financial planning research such as Morningstar.

For the purposes of determining research impact, we have used three different scoring metrics to analyze this year’s ARC. In all cases, oral presentations (breakout sessions where authors present their findings to an audience) were given twice the weight as research selected for a poster session (a less formal presentation of research that takes place within a large meeting space, displaying many posters available for review at one time).

Generally speaking, authorship rank (i.e., which author is listed first, second, etc.) is an indication of how involved each author was in the project. Therefore, three different scoring methods were used as an attempt to capture different ways of assessing how involved authors were in producing the research.

The first method was to assign equal credit to all authors. An oral presentation of a sole-authored research paper would earn an institution a score of 2.0 (1.0 for a poster session), whereas an oral presentation of a paper with five coauthors would earn the institution of each respective author a score of 0.4 (0.2 for a poster session). By this metric, Kansas State ranked first, followed by Georgia, Texas Tech, and Ohio State.

An alternative approach was also used, awarding all points to the institution of the first author listed on a paper, regardless of the number of coauthors. Using this approach, a paper presented at an oral session would earn the first author’s institution a score of 2.0 (1.0 for a poster session) regardless of how many coauthors were on a paper or what their affiliations were. By this metric, Kansas State ranked first, followed by Ohio State and then a tie between Georgia and Texas Tech.

A “middle of the road” approach is to award a higher share of credit to institutions with authors ranking higher on a paper, while still awarding some credit to institutions of lower-ranking authors on a paper (see more scoring details here). By this metric, Kansas State still ranked first, followed by Georgia, Texas Tech, and then Ohio State.

From an institutional perspective, it is also worth noting that there are many other ways in which financial planning programs are involved that are not measured here. For instance, among the top financial planning programs, Missouri, Ohio State, and Georgia all had representatives on the steering committee (among other universities), and individuals from Kansas State, Georgia, and Missouri (which alone had three individuals), served as additional paper reviewers. Across many different metrics, the influence of top programs on financial planning research was apparent at the 2020 ARC.

Notwithstanding the strong presence from top financial planning programs—as the four doctoral programs accounted for a combined 37% of all research, plus another combined 15% from Ohio State, Alabama, and Morningstar—the diversity of research by institution was again apparent. Compared to the 2019 ARC, though, which saw representation from a total of 69 institutions among authors at all ranks (and 42 at the first-author rank), there were only a total of 44 institutions represented among authors at all ranks, with first authors from 31 different institutions.

Industry sponsorship of the 2020 ARC appeared to be roughly on par with the 2019 ARC. Although there was again no named event sponsor (consistent with 2019, but not 2017 and 2018), three firms—T.D. Ameritrade Institutional, Northwestern Mutual, and Lincoln Financial—sponsored $2,500 best paper awards, which was an increase from two firms in 2019.

However, additional sponsorship seemed to be down, with only Zahn (lanyards) listed as an additional sponsor. Exhibitors were down considerably from 2019 (12 exhibitors) with the only named exhibitors including CFP Board, CFP Board Center for Financial Planning, PlanPlus Global, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Institute for Behavioral and Household Finance at Cornell University, and the National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE).

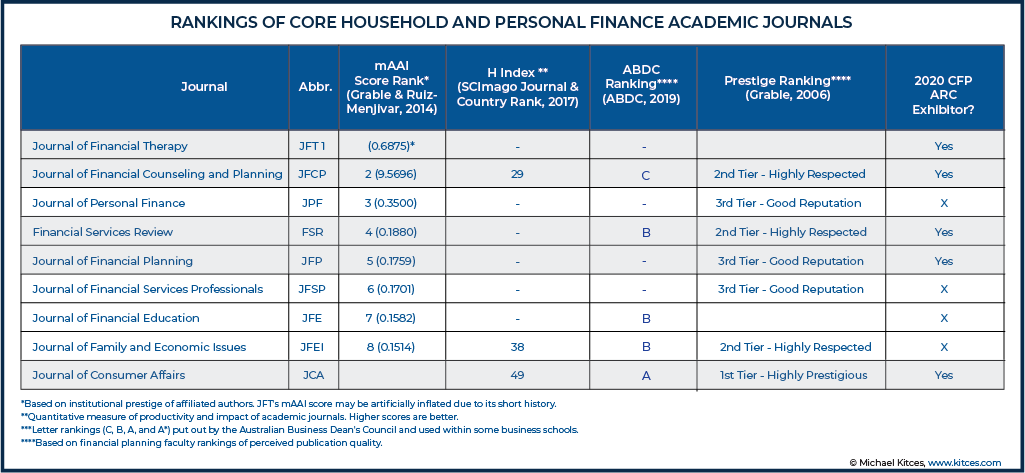

Journal exhibitors were consistent with prior years, included four of the top five core household and personal finance journals identified by John Grable and Jorge Ruiz-Menjivar in 2014:

Additionally, although not included among the “core” household and personal finance journals identified by Grable & Ruiz-Menjivar, the Journal of Consumer Affairs (American Council on Consumer Interests) was again also an exhibitor, which is one of the highest-ranking journals that regularly publishes content relevant to personal and household finance.

An Update on the Center for Financial Planning’s New Journal: “Financial Planning Review”

The ARC is a great opportunity to hear from the leadership of the Center for Financial Planning’s new journal, Financial Planning Review (FPR). Co-Editors of the journal include Dr. Vicki Bogan (SC Johnson College of Business, Cornell University), Dr. Chris Geczy (Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania), and Dr. John Grable (University of Georgia). Additionally, Dr. Charles Chaffin (CFP Board Center for Financial Planning) serves as the Executive Editor of the FPR.

In 2018, Financial Planning Review formally launched as a journal, and in the most recent year published the following articles:

Volume 2 (2019), Issue 1

Volume 2, Issue 2

Volume 2, Issue 3-4

A continued goal of FPR is to provide quality and timely peer reviews (FPR’s first readership report indicates an average time from submission to final decision of under 8 weeks), with the hopes that FPR will be a place that financial planning researchers think about submitting their highest quality work. So far, the journal has been quite competitive, with an acceptance rate of less than 10% of submitted articles.

FPR currently has a special issue call for papers on the topic of household finance and health. The submission deadline for this special issue is December 31st of 2020.

Practical Research Insights From The 2020 ARC

Consistent with past ARCs, there were many compelling research insights presented. From whether a bigger 401(k) investment menu offers more value than smaller menus to participants, to how much consumers are actually willing to pay for financial advice, and whether fintech ‘nudges’ can actually help clients by keeping them from overspending. Other topics of interest included whether financial advisors are effective at reducing client anxiety and whether brokers can comply with Regulation Best Interest (Reg B.I.) without actually being a Fiduciary.

Is A Bigger 401(k) Menu Actually Better?

In recent years, conventional wisdom regarding 401(k) investment option menus has emerged, which suggests that smaller investment menus within Defined Contribution (D.C.) plans are better than larger menus. However, in their paper, Bigger Is Better: Defined Contribution Menu Choices With Plan Defaults, David Blanchett and Michael Finke present compelling evidence challenging this conventional wisdom.

Like much conventional wisdom, there was some validity of the initial findings that smaller plan menus were better for participants. Initial studies found that having too many options led to “choice overload”, which could reduce plan participation if participants felt overwhelmed by having too many choices and would simply result in the participants choosing to do nothing as a result.

For instance, Iyengar, Huberman, and Jiang (2004) found that for each additional 10 funds added to a D.C. plan menu, employee participation rates declined by 1.5%. This was particularly problematic in a world in which default investment options were low-risk investment options that, while unlikely to decrease in value, were unlikely to provide the level of investment growth needed to help fund one’s retirement.

However, as Blanchett and Finke note, the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) brought about considerable changes to D.C. plans, including the option to place employees, by default, into target-date funds more suitable for providing the type of investment growth individuals need to fund retirement.

So, while the pre-PPA default option (generally a money market fund or similar product that would not lose value) was a very poor choice for most investors, the default post-PPA is actually a very good choice for most investors, and the dynamics are, therefore, now much different. Furthermore, for investors who do want to move away from the default option, it is not clear that fewer choices were ever a benefit for them.

Blanchett and Finke sought to test how plan size influences decision-making for investors in a post-PPA world. They used a dataset that included over 500 401(k) plans with roughly 500,000 participants. The plans included in that dataset had core investment menus that ranged from about 10 to 30 investment options.

What the researchers wanted to know was whether (a) default acceptance rates varied between plans with larger core menus (i.e., did the number of options available on the plan’s investment menu influence participants to accept or reject the default investment allocation?) and (b) whether investors who move away from the default plan option earn higher risk-adjusted returns with access to a larger number of fund options.

Blanchett and Finke found that larger core menus (e.g., 30 funds rather than 10) actually provided dual benefits. First, the larger core menus—presumably still inducing a sort of choice overload—pushed investors towards the default option at greater rates. This was a beneficial outcome because investors who use the plan default tend to outperform those who move away from the default option on a risk-adjusted basis. Second, those who did decide to move away from the default option also saw increased risk-adjusted returns (albeit still lower returns than those who just stuck with the default).

The authors’ findings have considerable implications for advisors who are consulting on 401(k) plan design. Rather than discourage employers from providing a large menu of funds which may be desirable to individuals who want to customize their portfolios, employers can provide the choice that is desirable to those who want to customize while also nudging most employees in what is likely a beneficial direction (to simply accept the target-date fund).

Specifically, the authors found that increasing the core menu from 10 to 30 funds increased the acceptance of the default target-date fund from 73.6% to 87.1%. The corresponding performance benefit to those who accepted the target-date fund was an average risk-adjusted alpha of about 54 basis points. At the same time, the expected alpha among self-directing investors was about 11 basis points higher.

It is worth noting that this study only considered 401(k) plans from a single recordkeeper. Future studies will be useful in confirming and extending these findings. For instance, it’s not clear whether these same findings would apply to other plan types, such as 403(b) plans. Furthermore, we don’t know how big might be too big (e.g., 100 funds may not be better than 30 funds). The composition of funds is also worth considering. Merely adding 10 large-growth funds would presumably not add the same value as adding a quality mix of funds to help participants build better portfolios.

But ultimately, as the authors conclude, contrary to conventional wisdom, it appears that bigger truly may be better (at least up to a point) when it comes to 401(k) plan core menus!

How Much Are Consumers Willing To Pay For Financial Advice?

As financial advisors try to reach new markets with innovative service models, the fee-for-service approach has obvious advantages in terms of not restricting access based on criteria such as the size of an individual’s portfolio.

However, the ability (and willingness) to pay are still important factors to consider, as prior Kitces Research has found that even hourly financial advisors are still working with highly affluent clientele, with average client incomes around $169,000 (right near the 90th percentile of U.S. household income). In fact, only 5% of hourly advisors surveyed reported serving clients with average levels of household income (and advisors in B/D or insurance environments were much more likely to be serving clientele with household incomes of less than $61,000 per year).

While little research exists to inform willingness to pay from a more typical consumer’s perspective, Wookjae Heo, Ja Min Lee, and Narang Park set out to explore this topic in their paper, Estimating Willingness-To-Pay for Financial Planning Services.

Heo et al. surveyed 997 U.S. respondents to examine how much they would be willing to pay for hourly, fee-only financial planning services. To explore this question, the researchers informed participants that typical hourly fees for fee-only financial planners in the U.S. are between $150 to $300 per hour. Next, they asked respondents if they would be willing to pay one of three initial prices to consult a financial advisor ($150, $225, or $300). From there, depending on initial responses to this question, individuals would be branched to follow-up questions inquiring about willingness to pay higher or lower hourly fees. Ultimately, hourly fees evaluated ranged anywhere from $105 per hour to $390 per hour.

Among the individuals initially assigned an hourly fee of $150, only 24% of respondents (94 out of 391 respondents) were willing to pay this hourly fee. As would be expected, the initial acceptance rate decreased as the initial offered fee increased, with only 16% of respondents indicating a willingness to pay $225 and 14% of respondents indicating a willingness to pay $300.

Of those who indicated they would not pay $150 per hour, only 11% indicated a willingness to pay $105 per hour, which suggests that even a rate as low as $105 per hour may be considered “too high” by a very significant portion of the U.S. population. In fact, around 73% of respondents indicated they were not willing to pay any of the prices offered to them during the survey, which again suggests there may be significant challenges for trying to reach less affluent Americans using an hourly fee strategy.

Because the sample surveyed by Heo et al. varied across different demographic characteristics (e.g., income, net worth, employment status, and gender), the researchers could evaluate how different factors were associated with willingness to pay. Individuals with higher income and positive net worth were willing to pay more for hourly financial planning services. Additionally, men and younger respondents were also willing to pay more.

As the authors note, future research can certainly expand on these findings by evaluating factors such as how perceived quality of services influences willingness to pay. It would also be interesting to see what price point entices a larger number of Americans (e.g., is $50 per hour still too much?), as the answer may have significant implications for structuring business models aimed at serving broader segments of Americans.

Furthermore, future research may identify that where a fee is paid from (e.g., a client’s bank account versus their retirement account) also influences willingness to pay, so perhaps regulatory policies that allow for financial planning fees to be paid from retirement accounts could help broaden access.

Can FinTech Nudges Help Prevent Overspending?

As clients are more connected to technology than ever before, there are many opportunities to use technology to help promote good financial behavior. In a paper titled, Fintech Nudges: Overspending Messages and Personal Financial Management, Sung Lee of New York University examines how messaging from a mobile application can influence spending behavior.

Lee was able to obtain data on users from a major Canadian bank with a mobile application that sent users various messages related to their financial behavior. For this particular app, users would log into their app and receive a message ‘nudge’ to indicate if their spending was above a certain level compared to their historical average. For instance, if a user had spent more than normal on groceries over a given time period, they may log in and be prompted with a nudge indicating that they spent well over their typical spending over that time period.

Spending categories included normal budget areas such as shopping, groceries, dining out, home, entertainment, travel, cash, and fees. Within the app, individuals could also see spending levels relative to their typical spending both overall and within certain categories.

Applying various types of statistical analysis to the user data, Lee found that the nudges from the application do appear to influence spending behavior. Specifically, Lee found that the day after receiving a nudge, users reduced their spending by about C$8.15 (or about 5.4% of their rolling daily average spending over the past 365 days). Additionally, Lee found evidence that users purchased fewer goods after receiving a notification and spent less per good purchased.

Not surprisingly, users were most responsive to messages related to their “shopping” budget category, presumably because discretionary spending is easier to cut that non-discretionary spending. Lee also found that the reduction in spending was not merely a short-term effect (e.g., avoiding a purchase the day after the notification but making up for it down the road), but instead resulted in a cumulative reduction that persisted over time.

Lee found that not all types of users were equally influenced by the app. He found that the nudges had a greater influence on users who were older, had higher levels of liquid wealth, were savvier with their finances, were new to the app experience, and who lived in more educated cities.

However, not all of Lee’s findings were necessarily positive. In particular, Lee found that individuals who received messages were 2.3 percentage points less likely to log into their accounts over the next 7 days, and 1.6 percentage points less likely to log in over the following 30 days. Lee attributes this behavior to the “ostrich effect”, which refers to a form of self-deception where individuals try to avoid exposing themselves to information that could provide discomfort.

Notably, while Lee finds lots of interesting examples of ways in which fintech can influence our lives, the magnitude of most effects is quite small. Certainly small benefits can accumulate and result in larger benefits in the long run but, at least for now, it does not appear that robo-nudges will radically alter client spending behavior.

While outside of the scope of Lee’s paper, advisors may also want to consider the ways in which advisor technology may unintentionally lead to ostrich effect behavior. Tools that provide too much information that clients do not perceive in a positive manner (e.g., declining portfolio balances during the recent downturn) could unintentionally lead to less engagement if they lead to clients trying to avoid negative information.

Do Financial Advisors Reduce Client Anxiety and Increase Confidence?

While much of the research on the use and benefits of financial advisors has focused on quantifying different ways in which advisors add value, often a significant portion of the value added is assumed to be attributable to behavioral coaching. Yet, there is still much we don’t know about the ways in which advisors actually influence their clients.

A team of researchers from Kansas State University—Matt Sommer, HanNa Lim, and Maurice MacDonald—sought to examine whether working with an advisor would help reduce anxiety and increase a client’s confidence in their ability to accomplish their goals.

To conduct their study, the researchers administered an online survey of 1,005 households through Research Now SSI (now Dynata), which specifically targeted 800 individuals (400 men and 400 women) with investable assets between $250,000 and $1M, and 200 individuals (100 men and 100 women) with investable assets in excess of $1M.

The researchers asked individuals questions about both their levels of financial anxiety and investment confidence. They also asked about whether the household works with a professional financial advisor, which they defined as “a paid professional who provides ongoing customized advice and service to you about your investments – not just a one-time transaction.” They also asked for information about how respondents divvy up financial decision-making within their household and demographic characteristics such as education, employment status, age, and ethnicity.

Interestingly, Sommer et al. did not find a relationship between financial anxiety and the use of a financial advisor. The authors speculate that those who do not use the services of a financial advisor may already have low levels of financial anxiety. They did find that those who reported using a “research-oriented” investment style were less anxious, those who were employed full-time were more anxious, those who had a professional life event (e.g., losing a job) in the past year were more anxious, and those with more assets were less anxious.

The researchers did find that individuals who worked with a financial advisor reported a higher level of investor confidence. Additionally, they found that couples who make decisions together had a higher level of confidence, self-employed individuals had higher levels of investor confidence, and that age was negatively associated with investor confidence below age 48, and then positively associated with investor confidence above age 48.

From a practical perspective, we likely need to know more about the factors leading to the use of a financial advisor (or not) before we know how to interpret the finding regarding advisors not reducing client anxiety. As the authors note, it is quite likely that financial anxiety is itself a precursor to the use of a financial advisor, so there is a selection issue with respect to who ends up in the “uses an advisor” and “does not use an advisor” categories.

In future studies, it will be helpful to try and determine whether the use of an advisor influences financial anxiety among those who choose to use an advisor, to more specifically identify the actual causal relationship between advisor use and anxiety. Similarly, it would be interesting to see whether the use of an advisor causes any change in investor confidence, either in the short- or long-run.

Nonetheless, it is nice to see research that is beginning to empirically explore many of the value-adds of working with an advisor that are generally just assumed, and it is particularly nice to see a study using a sample of households with high levels of investable assets to better represent the population that financial advisors in the U.S. are working with.

Can A Broker Comply With Regulation Best Interest (Reg B.I.) Without Being A Fiduciary?

With the passage of Regulation Best Interest (Reg B.I.), there has been a considerable increase in the amount of attention directed at what a “best interest” should mean, how it is perceived by consumers, and what duties professionals must meet to fulfill the obligations to clients.

In a forthcoming paper titled Can a Broker Comply with Regulation Best Interest without being a Fiduciary, Jim Pasztor, Aman Sunder, and Rebecca Henderson explore financial advisors of perceptions regarding what a “best interest” means, and particularly how a best interest standard compares to a fiduciary standard.

Using a sample of 130 alumni from the College for Financial Planning, the authors examined whether different types of advisors (e.g., representatives of RIAs versus broker-dealers, CFPs versus non-CFPs, etc.) had different ways of understanding the best interest standard and how it compares to a fiduciary standard. Notably, their sample was skewed towards more experienced professionals, with 64% of respondents having 15 years or more of experience within the financial services industry.

First, the researchers asked individuals to provide their understanding of whether Reg B.I. applied to them. Notably, advisors at pure RIAs (compared to those at broker-dealers or dually-registered RIAs) were more likely to be mistaken or confused about whether Reg B.I. applied to them. Additionally, CFP professional and more experienced financial advisors were less likely to be mistaken or confused about whether Reg B.I. applied to them.

Interestingly, these relationships were observed despite the fact none of the same comparison groups exhibited statistically significant differences in their confidence of their knowledge regarding Reg B.I. or a fiduciary standard, suggesting that advisors in pure RIAs, non-CFPs, and less experienced advisors may be somewhat overconfident in their knowledge regarding Reg B.I.

Advisors participating in the study were then asked additional questions regarding their perceptions of Reg B.I., including the following:

- Is a fiduciary duty a higher standard than Regulation B.I.?

- Will Regulation B.I. have any positive impact on the financial services profession?

- Does the Fiduciary standard do a better job of looking after clients’ best interests?

- Does Regulation B.I. provide more clarity to clients?

Again, significant differences between groups were observed. For instance, advisors at broker-dealers and more experienced advisors were less likely to believe that a fiduciary standard is stronger than Reg B.I., women were more likely than men to believe that Reg B.I. would not have a positive impact on the financial services profession, CFP professionals and advisors at RIAs were more likely to believe that a fiduciary standard does a better job than Reg B.I. in looking out for a clients’ best interest, and CFP professionals were more likely to believe that Reg B.I. does not provide more clarity to clients (although more than two-thirds of all advisors felt that Reg B.I. would not provide greater clarity, so even though CFP professionals measured higher, there was a strong majority belief in favor of this position amongst all advisors in the study).

While the CFP professionals and advisors at pure RIAs are correct to perceive Reg B.I. as a lower standard than a fiduciary duty, it is perhaps not surprising that advisors at B.D.s are more likely to believe they are being held to an equal standard. Brokers may naturally want to be able to tell their clients they are held to the same standard, and, although there are some differences, Reg B.I. does get very close to a traditional fiduciary duty.

On the other hand, pure RIAs may also be more attuned to the nuanced differences between the standards, since they may continue to use the distinction between the two standards as a selling point when meeting with consumers.

It is also noteworthy that, despite the potential benefit of brokers being able to claim they must act in a client’s best interest, a strong majority of all respondents agreed that the new standards would not provide greater consumer clarity. This finding is consistent with continued consumer confusion observed in consumer testing.

One practical takeaway for all advisors is a reminder of the importance of being up to date on Reg B.I. and understanding its implications for you as an advisor. Across all comparison categories evaluated in this study, a minimum of 19.5% of advisors within a group was confused or mistaken about whether Reg B.I. applied to them, suggesting that many advisors still need to get up to speed with the new rules before they take effect on June 30th, 2020!

Overall, the fourth CFP Board Academic Research Colloquium once again brought together a strong mix of academics and practitioners to present and discuss financial planning research.

Given the steep decline in attendance after the conference was separated from the Registered Programs Conference, it will be interesting to see how the CFP Board responds and whether these conferences can be brought back together in the future.

Regardless, the ARC continues to be a conference worthy of attending for both academics and practitioners who wish to engage in academic research.

Leave a Reply