Gallup is out with some new data on American views toward investment markets that I think is worth discussing.

Overall, about 55% of US households have some investment in the stock market (through either individual equities or mutual funds), which is unchanged from two years ago but below the peak of 63% from shortly after the turn of the millennium. The fall from 63% to 55% doesn’t sound like much, until you remember that there are 128 million households, so we’re talking about approximately 10 million less families involved in stock investments than there were 20 years ago.

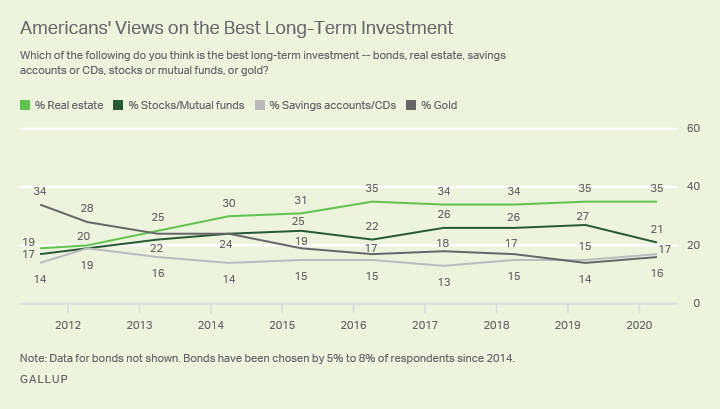

Americans have become less likely to view stocks or mutual funds as the best long-term investment after U.S. markets dropped by more than a third as the economic implications of the coronavirus outbreak set in last month. The current 21% naming stocks as the best investment is down six percentage points from last year and is the lowest Gallup has recorded since 2012. Real estate continues to rank first, while gold and savings accounts trail stocks.

Gallup asks whether respondents prefer real estate to stocks for the long-term and, of course, they do. But to me, this is a confusing question because, for most of the people being surveyed, the only real estate they have any experience with is their own home. The value of their own home doesn’t fluctuate each day because there is no ticker. And they have emotional bonds to their homes – it’s where their children have grown up and where their fondest memories are made. You can’t throw an eighth birthday party for your daughter in an IRA account.

Real estate, at 35%, remains the most favored investment to Americans, as has been the case since 2013, when the housing market was on the rebound. More than a third of Americans have named real estate as the top investment since 2016.

I think what’s most interesting about the new survey is the fact that the affinity for stocks has never really recovered among Americans dating back to the twin bear markets of the aught’s decade. They watched the S&P 500 get cut in half twice within seven years and they never forgot it, despite the massive gains since then, with the Dow Jones rising from 6500 to almost 30,000 between 2009 and early 2020. They remember living through the economic recessions that accompanied those two stock market crashes, and those experiences stuck with them.

Another variable involved is that not everyone who participated on the way down was able to participate on the way back up, which would be enough to sour people on investing for the rest of their lives in many individual cases. This is the kind of fateful cruelty that gives rise to the idea that things are rigged and that someone else benefited from their own misfortune.

And now, the percentage of households that believe investing in stocks for the long term is a good idea versus a bad idea is precisely split down the middle, with wealthier households more likely to say yes and lower income households more likely to say no. There’s a lot to unpack inside of this distinction, but suffice it to say that life experience plays a big role – if you’ve never had excess wealth to invest, and have never had the experience of benefiting from a rising stock portfolio, it’s hard to have the perspective that doing so would be more attractive than, say, owning a home and not having to pay rent to someone.

Now imagine asking this question of people right after they watch the stock market fall 30% in three weeks while having a home to shelter in has never been important to their survival! What do you think they would say?

Something else worth pointing out is that when you see a wealthy person in your own community, it’s impossible to know how much that person has invested in the stock market. But your can see their house and their property with your own two eyes. Cars and houses and boats are more evocative of wealth than mutual funds. They are tangible evidence of success, so it makes sense that people who haven’t yet arrived at success would be covetous of the type of wealth they can see and touch and walk around inside of.

Home prices in the United States have returned something like one percent over the long, long term on an inflation adjusted basis while stocks have returned something like seven times that. Of course, there are many regional differences over the decades. Homeowners may understand conceptually that the value of their home rises and falls through the years, but they don’t feel this “volatility” until they go to sell or buy. Additionally, the cost of owning a home is not just what you pay for it. Maintenance, taxes, remodeling, repairing damage, etc are rarely factored in when someone brags about how cheap their house was when they bought it 30 years prior.

This is not to say that owning a home is either a good or a poor investment, especially when we drag back in all of the emotional aspects of having a place of your own to live in. It’s an individual choice, regardless of whether or not the price appreciation can compare to a portfolio of stocks. Which is why it’s so hard to get survey respondents to answer the real estate versus stock portfolio question objectively.

There is a segment of America that has the luxury to do both, but unfortunately, it’s not large enough.

Source:

Stock Investments Lose Some Luster After COVID-19 Sell-Off (Gallup)

Leave a Reply