Executive Summary

The study of behavioral finance has significantly enhanced our understanding of real-world financial behaviors, and (in the process) has given advisors insight into the underlying behavioral biases that cause clients to make not-always-rational decisions. Yet while examining the irrational behavior of individuals in the context of personal finance, behavioral finance focuses mainly on how individuals behave but doesn’t always do a great job explaining why they make the choices and have the biases that they do, nor in particular what financial advisors should actually do about those behaviors. Thus, while academic research on behavioral finance has imparted value to the financial planning industry, it still has a tendency to fall short when it comes to providing effective, practicable applications that advisors can bring back to their firms.

In this guest post, Jay Mooreland – Founder of The Behavioral Finance Network in Saint Paul, Minnesota – examines the challenges financial advisors face in actually implementing behavioral finance concepts effectively with their clients, and how advisors can instead use behavioral coaching not only to help clients stick to their plan but also as a way to differentiate themselves from other advisors.

One of the most common challenges with the actual application of behavioral finance is dealing with the overabundance of ‘noise’ described as ‘behavioral finance’ presented by experts and non-experts alike, which frequently offers little value to the financial advisor who isn’t just trying to understand what biases may be causing their clients to behave the way they do, but who are trying instead to help their clients change their behavior and actually stick to an agreed-upon financial plan by managing the influence of those irrational behavioral biases. As the recent market volatility from the coronavirus pandemic illustrated, simply ‘knowing’ that clients may be exhibiting behavioral biases that make them want to sell at the market bottom didn’t itself do much to talk them off the ledge.

Instead, behavioral coaching can be an effective way to help clients make better choices if done proactively and consistently. And notably, while education is a key factor in behavioral coaching, the best coaching support won’t come from advisors who just provide their clients with facts and rational statements, but will instead be more likely to come from advisors who also understand the importance of message timing (i.e., when a client would most benefit from certain ideas, which depend not just on the economic environment or current legislative landscape, but also on what is happening in the client’s own personal, financial, and emotional life), and how best to deliver the messaging (e.g., crafting messages that are easy, smart, and fun) so as to effectively stick with a client.

Advisors can also employ the principles of behavioral finance to connect and engage with clients and prospects to grow an advisor’s business, as it is critical for financial advisors to use appropriate framing (i.e., advisors can communicate most successfully when they keep the client’s point of view in mind, versus relying only on their own perspective) and understand how clients will perceive and interpret the messages they convey. Furthermore, messaging and communication that incorporate psychological factors (e.g., emotionality and connection) will generally tend to be more impactful in influencing clients’ behaviors than rationality and logic.

Ultimately, the key point is that while behavioral finance research may have limited application for financial advisors looking for practical ways to directly help their clients, advisors can use behavioral finance principles to effectively help their clients make better choices and stick to their plans with a more coaching-oriented approach. Furthermore, principles of behavioral finance that emphasize proper framing and the psychology of communication can help advisors differentiate themselves with value headlines that are personal, impactful, and that connect effectively with clients.

Behavioral finance has become a very popular topic among the investment community. There is a designation, the Behavioral Financial Advisor (BFA), and terms such as “behavioral coach” and “behavioral wealth advisor” have become buzzwords. It is very likely that an investment conference will have at least one educational session on behavioral finance (if not being the subject of the entire event).

Behavioral finance, as a science, begins with theory. Theories are often developed and taught in academia by professors holding PhDs in finance, economics or psychology, who author behavioral finance white papers and may present on their research at advisor conferences.

Yet while academics do a good job identifying and describing the problem and providing basic guidance to improve outcomes, they tend to fall short when it comes to providing effective applications that advisors can actually use in their firms. This shouldn’t be too surprising as academia is one realm, whereas the advisor’s practice and dealings with clients are another. Knowing the engineering mechanics of how a car operates is quite different from actually learning to drive one.

I have been a financial advisor since 1999. I spent nine years at wirehouses, and the last 11 years with an independent broker/dealer. My professional experience has been in financial planning and servicing retail clients. During the financial crisis, I went back to school (while still an advisor) and obtained a master’s degree in Applied Economics.

While I was studying for my thesis, I stumbled upon behavioral finance and decision-making under uncertainty. Applying behavioral finance to improve investor results ended up being the core of my thesis and continues to drive my passion today.

I am indebted to academia for all the things I have learned, but I believe many of its recommended applications are not effective, and in some situations may even result in more harm than good.

For example, academia often suggests that advisors talk about various behavioral finance biases with their clients. The very word “bias” has a negative connotation, and talking to clients about how they are overconfident, anchor, or exhibit loss aversion is not a positive discussion, and can even potentially serve to offend the client. After all, simply “explaining” to clients that they were panicking in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic market volatility, and were engaging in recency bias by overextrapolating the recent market decline, didn’t itself make any clients suddenly ‘stop panicking’. Instead, advisors can be more effective by focusing on proactive mitigation of the biases rather than merely identifying them for clients.

I founded The Behavioral Finance Network to combine what I’ve learned from academia with my own practice as a financial advisor to provide other advisors with instructional content and coaching services to help them develop effective and on-going behavioral finance applications for their business.

What is Behavioral Finance?

Behavioral finance examines irrational behavior in the context of personal finance, and examines how individuals may irrationally react to markets, market behavior, portfolios, and investing. It recognizes that we are not rational agents, which goes against one of the principal tenets of traditional economic theory positing that all people are rational.

The truth is that we are emotional and make mistakes in our judgements because we are influenced by behavioral biases. These biases can encourage emotional and hasty decision-making, which can lead to costly mistakes and is not always beneficial in an investment context. Though while emotions can indeed lead to costly mistakes, the merit in understanding how emotions play a role in rational decision-making cannot be overlooked as a means of dealing with irrational behaviors. The study of evolutionary psychology has even highlighted the value of examining emotions and applying psychological principles to personal finance.

DALBAR, Inc., JP Morgan, and Morningstar each have performed separate studies to quantify the cost of our biased (human) decisions. While each study’s methodology and results differ, they each found a so-called “behavior gap” between what the markets deliver, and the returns investors achieve for themselves, where behavioral biases resulted in actions that caused an unnecessary drag on performance. And for some, that drag can be substantial.

For example, if an investor cashes out during a period of volatility, undesirable news, or a market forecast (Q1 2018, Q4 2018, Q1 2020), then the failure to participate in the rebounds that have followed may greatly reduce the chance of reaching their performance and financial planning goals. The value in applying behavioral finance is not in identifying a particular behavioral bias, nor is it simply educating our clients… it’s about what we do to improve the investor experience and results and help them to earn what the markets can provide.

In other words, drafting a financial plan or investment strategy is not the major challenge for advisors. Rather, the challenge is finding ways to help the client adhere to the plan. As while every market move and every news story can serve as a temptation for a client to abandon their plan, the effective application of behavioral finance can be a significant value to our clients.

Challenges of Applying Behavioral Finance – Dealing With Behavioral Finance ‘Noise’

There are various challenges to applying behavioral finance effectively in an advisor’s practice, and behavioral finance ‘noise’ is one of the most prevalent. As while there are a lot of ideas about how to apply behavioral finance in an advisor’s practice, some of which are valuable and effective, much of it is nothing more than distracting noise.

Due to the popularity of behavioral finance, many firms now have behavioral finance ‘experts’ that speak and write on the topic. The scope of these ‘experts’ is far-reaching, from salespeople who have simply read a book on behavioral finance, to bona fide professors with PhDs in economics and/or finance. As far as PhD’s go, their research is valuable and eye opening. However, they often miss the mark when it comes to extrapolating research findings into how a practitioner can apply them.

For instance, in academia there is a significant focus on trying to identify what the behavioral biases are and when they’re occurring in practice with a client. But while identifying a bias may be useful for an exam, just identifying the bias isn’t actually a solution to the bias in the real world. Furthermore, seldom do biases work independently of each other.

As an example, let’s say the market is going down in the face of a global pandemic, news has turned negative, and your client wants to abandon their plan and go to cash. Which bias are they displaying? Let’s see, certainly you may identify the bias of loss aversion. Other biases in play here may also be regret aversion, recency, availability, representativeness, anchoring, overconfidence, and perhaps others such as framing.

Yet the key point isn’t just that it’s hard to know which is occurring… it’s also that it doesn’t necessarily matter. Even if you could nail down the bias (or mix of biases), that information alone is not helpful. Rather, we should be spending our time and energy in mitigating the influences that behavioral biases exert on the investor (some strategies are discussed in a later section, below).

In turn, some white papers on applying behavioral finance do suggest that the advisor “reinforce to the client the important goal of managing behavioral biases” or “dampen behavioral tendencies in difficult markets”. Still, though, these statements provide goals, but lack real application. How are we to dampen these tendencies? How do you actually manage behavioral biases?

Some suggest you talk to clients about their biases, and educate them. I strongly disagree. Want to upset your client and sound elitist? Tell them they have a bias, or better yet go ahead and define several of them. “Mr. Client, I am constantly educating myself to be a better advisor, and I have been learning a lot about behavioral biases. What I have learned is that you exhibit the overconfidence bias, in addition to the availability and anchoring bias. But the good news is that you have me to identify these biases!”

I hope no advisor would actually say that, but you get the idea that talking about biases, miscalculations, errors, and emotions is a sensitive endeavor. And just being able to identify them and point them out doesn’t necessarily help a client change their behavior for the better. You may be well intentioned, but it can damage your relationship. Remember that how you say something is just as important as what you say.

Behavioral Coaching As Effective Application Of Behavioral Finance Research

Educating others with facts is seldom an effective motivator or catalyst for behavior change – even when the education clearly demonstrates we would be better off doing A than B.

Take losing weight as an example. We all know the solution is straightforward – burn more calories than you consume. Simple in theory, yet incredibly difficult in practice. Same thing with working out. It is fairly easy to understand how to lift weights safely, yet many people hire personal trainers. If it were as easy as simple education, personal training would be one meeting and done. Or everyone would solely watch a series of YouTube videos.

Still, personal training is a booming industry because people have a hard time doing it, despite knowing what they should do. Some can watch a video and do it themselves. The rest pay for, and value, the coaching and accountability a personal trainer offers.

Effective behavioral coaching is becoming your clients’ personal financial trainer – making sure they don’t hurt themselves. If we want to help investors make better choices, we need to teach correct perceptions and realistic expectations. And to be effective, it needs to be done proactively and consistently.

Unfortunately, behavioral coaching is an ambiguous term. It has become a buzzword and is often misapplied. Anyone can call themselves a behavioral coach, but what does that mean? One advisor may have a few conversations about biases with clients, and call himself a behavioral coach. Another advisor may define biases she sees in clients, and provide a white paper on how to behave better.

What really matters is how effective you are in coaching your clients. The message is one thing, how you frame it is another. Effective coaching influences better financial decisions and improves the investor experience. Talking a client off the ledge is good; making sure they never get there is better.

Examples Of Effective Behavioral Coaching

An element of behavioral coaching is educating, but not with factual and rational statements, or a white paper defining and explaining behavioral biases.

Instead, we consistently and proactively teach correct perceptions, and reinforce realistic expectations using timely examples. These messages go beyond volatility and performance. It’s about how clients may feel at different times, and temptations that clients are likely to face. You may have created a great plan for your client, but the media, in conjunction with our behavioral biases, are powerful temptations for investors to abandon their plan.

Once you know what perceptions and expectations to share, the next step is to figure out how to share them. Just because you send your client an email doesn’t mean they are reading it or find value in it.

In my years of producing behavioral finance content, I have found that content that is easy, smart, and fun, works very well to retain clients’ attention. Additionally, messages that are timely can also be very effective at reinforcing a valuable perception. In my experience, advisors report increased open rates, and clients are actually engaging with them – responding back with comments. Some advisors have also reaped the benefits of their clients sharing the content with others. Clients may not feel comfortable talking about finances with their friends, but they are happy to share novel content with the very people you want to get in front of.

Example #1: In July 2019, an advisor from Morgan Stanley shared this fun and impactful behavioral article with a client and landed a $1.6 million referral because his client shared the message with one of his friends. It was different and a bit humorous, and most importantly, the message was spot on!

Last month, a single bet on Tiger Woods winning the Masters resulted in a $1.2 million payout.

This was not a bet made by a wealthy individual or professional gambler. Rather, the bettor was a self-employed day trader saddled with a mortgage, two student loans and two car loans. He describes himself having a background in finance and considers himself “a responsible guy”.

I don’t know how responsible it is when someone in significant debt places an $85,000 bet on a single outcome. What would cause “a responsible guy” to do something so risky?

How Reliable is a Hunch?

He got lucky. Plain and simple. But that isn’t the way he sees it. “I just thought it was pre-destined for him to win.” It was a “feeling I had that led me to bet on Tiger in the first place.”

It was a feeling, a hunch. And because of the positive outcome, he may overestimate his ability to identify future “pre-destined” outcomes. Or he may allow his feelings to override logic and reason when making future financial decisions.

Skill Versus Luck

Luck happens in life. Sometimes it goes our way, sometimes it doesn’t. Outcomes, especially in the short term, are seldom evidence of skill or even wise decision making. They are more likely driven by luck or chance than skill. The same is true with investing.

As investors, we sometimes confuse luck with skill. Skill in investing is rarely demonstrated by short-term outcomes; luck and chance rule that time period.

Investment skill is often demonstrated by discipline to a strategy and patience. Constant fluctuations in asset prices and the role of luck make this very difficult. We want instant feedback, and sometimes we get impatient. But that is what separates the skillful investor from all the rest – staying the course.

© 2019 The Behavioral Finance Network

And while using messages that are easy, smart, and fun is certainly a good way to get clients’ attention, topics that are pressing and timely are also very effective, and can be used to educate and inform clients – especially when headlines can lead clients astray.

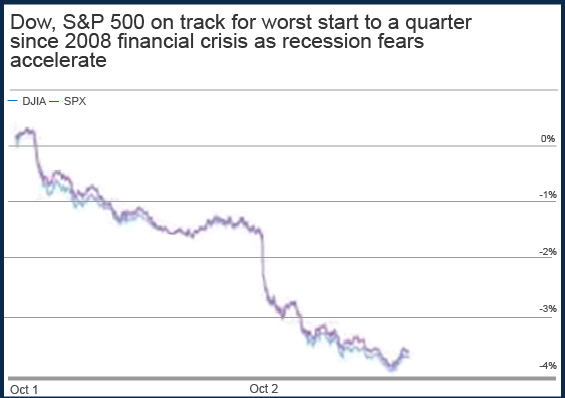

Example #2: October 2019. A popular financial news website led with a headline that the start of Q4 was the worst start to any quarter since the 2008 financial crisis, due to recession fears. This propaganda hit the trifecta: compare to the 2008 crisis, mention recession fears, and show a chart that makes it appear that markets are falling off a cliff.

In order to pull off this lunacy, the media had to show a chart of less than two trading days.

This was so good that I created a one-page article for advisors to send out to their clients and prospects. The article contained the same graphic above, and after a short intro, said:

The market ended up being positive in October, but even if it had been negative, it would have been a grave mistake to make investment decisions based on headlines and fear mongering. Allowing the media to influence financial decisions is one of the gravest errors an investor can make.

The financial media exists to get your eyeballs (so they can sell ads and make money). The media could care less about your values, feelings, or aspirations. In fact, they will often employ fear (which influences investors to make poor decisions) for their own pocketbooks.

I know how alluring these emotional headlines can be. The media is a master at getting our attention/eyeballs. My job is to help you overcome emotional impulses, and make thoughtful decisions that are in line with your plan.

This is just another example (among many) of why we need to ignore the media.

© 2019 The Behavioral Finance Network

You can see that there is definitely an opportunity for education here. But it’s how advisors are delivering the education. It is proactive, and this main theme of “ignore the media” was repeated several times in the course of a year by advisors with different examples.

Timely content helps us reinforce core perceptions and expectations, without sounding like a broken record. And these stories can be told in an email (as in the previous examples), or in a video shared with clients.

Example #3: In late October, this video, called “Beware of Hype” about the WeWork debacle, showed several pictures and graphs illustrating how the company was valued at $47 billion at the beginning of 2019, and investment banks were telling the company they could be worth as much as $100 billion.

WeWork tried to go public at $16 billion in September and ended up getting a cash infusion from Softbank at an $8 billion valuation. How can a company lose all that value when fundamentals did not change?The hype wore off. That was the central message. Hype is very alluring and exciting, but it can cause us to be blind to fundamentals and asking essential questions before making an investment.

The message ends with, “And that’s why it is always best to make decisions based on your plan rather than the hype of the day.” This is likely a message you have shared with your clients. But when coupled with a timely story, its ability to influence perception, and ultimately decision making, is enhanced.

Effective behavioral coaching is not a dry, boring statement about what a client should do. The messaging is empathetic, yet direct. The messaging is easy, smart, fun, and ideally timely to something that already has relevance to the client (e.g., from the current news cycle).

Behavioral Finance in Other Parts of Your Business

Behavioral finance is using psychological principles in the business of finance and economics. But the application of psychology doesn’t have to be reserved to improving our financial decision making. We can take the same principles to improve many aspects of our business, especially the way we communicate.

The need to connect and engage clients is very important these days. Connecting and engaging is psychologically deeper than contacting or talking to someone. It’s not so much what we say, but how we say things that matters. In psychology they call this “framing”. The way we frame a message can have a significant impact on how the other person perceives us and interprets the message. What you say isn’t always what the other person hears. And this is especially true in the financial realm.

Think of the ambiguous terms we throw around all the time as if they had one universal definition. For example, advisors will often state (either verbally or in written material) that they work with high-net-worth individuals. What is “high net worth”? Is it $1 million, $5 million, $25 million…? And would the prospective client know what the advisor’s definition was intended to be? For many clients, “high” net worth is something they evaluate relative to where they already are, which means “high net worth” is never actually about them, and is always about someone else who has more than they do!?

How about “risk”? That is ambiguous, too. Some people define risk as opportunity, others view it as loss potential, and others may interpret risk as simply uncertainty or the unknown. What do you mean by “risk”, and more importantly how does the person you are communicating with define it?

Perhaps this is the greatest lesson about communication. It’s not about you. It’s about your audience. You need to get out of your perspective, and see things through your clients’ lens. And remember, most humans are more influenced by psychological factors than then are by rationality/logic. Be sure your communications reflect that fact.

Differentiating Yourself

We work in a commoditized industry. Just about everyone offers a plan, a portfolio, and access to a human advisor, for some price. That price can differ drastically from full-service advisors to highly-scaled virtual advisory services that charge next to nothing. Unfortunately, because price is often the only clear differentiator, it has a lot of power to influence the investor’s decision.

I can’t tell you how many financial advisors’ websites say something about how they are different. Then I look at what makes them different, and they talk about a plan, a process, and caring about their client. Umm… that’s not different. That is what every advisor offers and says. Just because you say you are different, doesn’t make it true. This is one of the hardest truths for advisors to understand – their processes and deliverables really aren’t that different from one another. Those that ignore that truth may miss the opportunity to progress and increase their value. Those that face it head on and do something about it may be able to improve their game, and ultimately their business.

Do you actually offer something different? I would say that effective application of behavioral finance is different, but you still have a challenge. Most advisors don’t know how to effectively apply behavioral finance. And how do you frame such to a client or prospect? How do you ensure that the client perceives whatever you offer as different and superior to your competition?

This is where proper framing, and the psychology of communication come in. And it all starts with your value headline. Notice, I did not say “value statement” or “mission statement”. People don’t read these days; they skim and scan. You need to figure out what you want to highlight, and make it pithy and personal to you.

This is not an easy exercise. I work with advisors to come up with unique headlines that represent what they most want to say. This is often done through strategy calls, brainstorming sessions and back and forth emails. But with each one, we eventually find it. And then we build on it, ensuring that we frame every message in a way that supports the value headline and adds the personality of the advisor – because you are what is unique. You are what the client is buying. The mental energy required is different from the numbers you crunch; that is why most advisors don’t do it. It isn’t easy, but it often results in significant dividends.

Perhaps my favorite example of creating a value headline came from initial brainstorming sessions with an advisor who wasn’t getting anywhere. Two calls and several emails resulted in lots of ideas, but nothing that really clicked. Finally, we were on a call and out of desperation he said, “Look Jay, I’m just not a salesperson, I’m not good at this marketing stuff. But I’m a really good advisor.”

At that point it hit me – his passion came out. For me, it was a no brainer because I finally saw him for who he is and how he wants to be portrayed. Within a week, his value headline was prominently displayed on his website after his company name, “Terrible Salesman, Pretty Good Advisor” with a subheading, “Just Facts, No Fluff”.

This was funny and it was very true. It captured the essence of who this advisor is, and he got excellent feedback from clients and others in the industry. A great value headline is one that shows your prospects, in less than two seconds, who you are and what you will do for them in a unique and compelling way.

Behavioral finance in applied practice with clients is somewhat ambiguous. There is no one book or formula on how to apply behavioral finance. Academia and many white papers encourage advisors to learn the biases, identify the biases, and then educate the client. Empirical evidence, and perhaps your own experience, tells us these are not effective. They may make you feel like you are doing something different; but that doesn’t mean it is effective.

The effectiveness of behavioral finance application can only be judged by your clients. Does it engage them, and do they reply to the messages? Do they find value in the messages? Do they share the messages with others? Does it improve both investor behavior and experience?

Application of behavioral finance is something new, and may require trial and error to figure out what works best for you and your practice. There are a few ideas outlined in this article to help you, but they are by no means inclusive.

And “behavioral coaching” is not a Holy Grail. I have learned through many years that there are people that cannot be helped. In most cases, those clients need to be fired. It means they don’t see you as a trusted advisor.

Still, for many investors, behavioral coaching can help move the needle along the continuum of emotions and rationality. And isn’t that our job? Give each client the best odds at reaching their goals, despite any biases they may have.

Leave a Reply