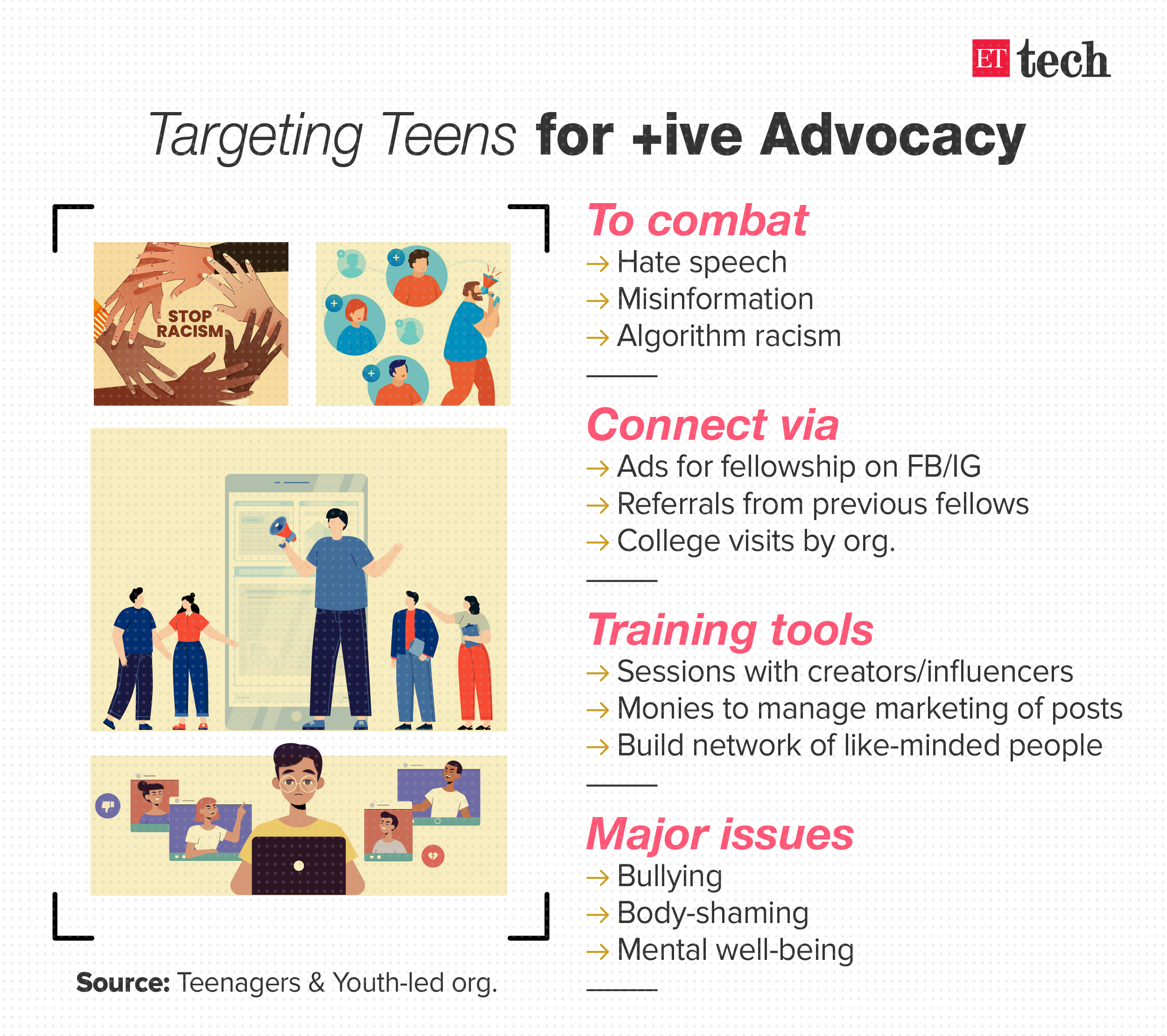

Instagram is working with a group of youth-focused organisations to train teenagers on how to build safe digital spaces to discuss issues like bullying, body-shaming, mental health, loneliness and gender diversity, among other matters that cause stress and anxiety, especially among adolescents.

This involves teaching teens how to create catchy content for positive advocacy, giving them advertising budgets to amplify their content’s reach, tutoring them on the usage of hashtags, instructing them about the art of tagging the right people for their post to travel the farthest, and most importantly, preparing them to deal with trolls and hate-mongers online.

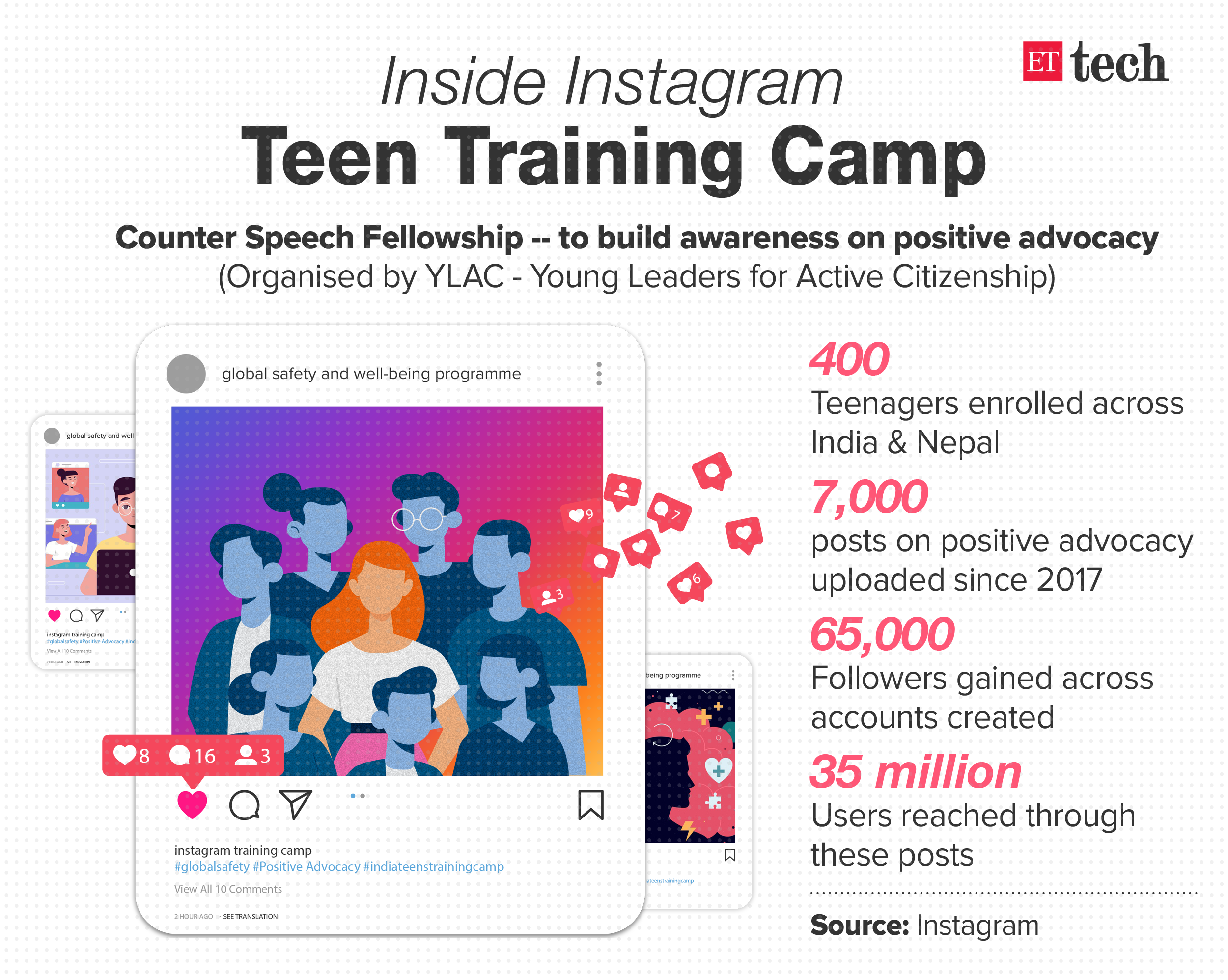

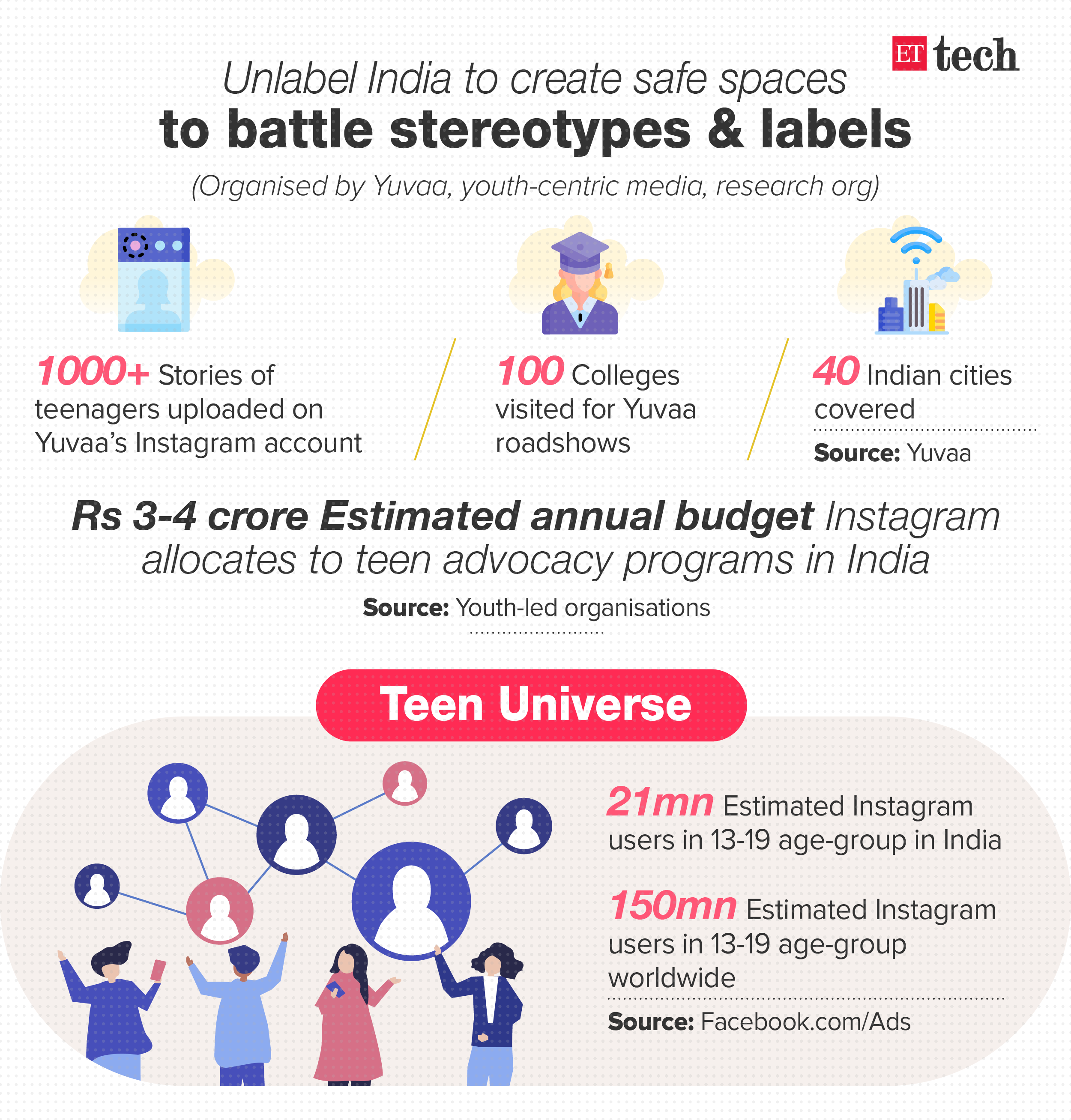

The photo-and-video-sharing platform from Facebook spends Rs 3-4 crore annually to push these initiatives in India as part of its global safety and well-being programme, said people aware of the initiatives. Besides collaborating with external youth-focused companies, they also roll out ads across Facebook and Instagram accounts of parents and teenagers promoting these programmes that teens can enrol themselves in for free.

Instagram started these initiatives in several countries, including the US, India, Nepal, Brazil and Australia, three years ago. Around that time, reports of online hate speech leading to violence had begun to surface in different parts of the world. As of today, there have been 500,000 sightings of hate speech in online conversations in 97 different languages across 178 countries, as per data from online-hate-speech-tracking company Hatebase.org.

For the longest time, Instagram steered clear of issues regarding online hate speech what with its image of a platform that was only meant for all things aesthetic-looking. However, in the last couple of years, hate speech has infiltrated Instagram, too, with users resorting to visual means to present misinformation, even as its parent company, Facebook, and its other sister concern, WhatsApp, came under the scanner for spreading fake news and hate speech.

Over the last few weeks, this has culminated to a host of big-league advertisers like Unilever and Starbucks boycotting advertising on Facebook.

Guiding Impressionable Minds

Late last year, global publications suggested that Instagram is fast becoming the new home for the proliferation of racist memes and screenshots of fake news.

Organisations working with school-and-college students said these developments affect young adolescents the most. “Because teenagers often don’t have a safe space to process this kind of violence and rage,” says Ruth Mohapatra, communications manager of The YP Foundation, a Delhi-based youth-led organisation.

Compared with social media platforms Twitter and Facebook, Instagram has a relatively larger population of teenagers on board, second only to TikTok.

According to data available on Facebook.com/Ads, the parent company’s advertising vertical, there are 21 million users in the 13-19 age group on Instagram in India and approximately 150 million such users globally.

“We feel it is our responsibility to ensure that they have a safe and comfortable experience while expressing themselves and sharing their passions and interests,” says Tara Bedi, public policy and community outreach manager, Instagram India.

If spreading hate and misinformation online requires creativity and strategy, countering it requires it even more. When working with teens to help counter said issues, it also requires listening to their voices that are often snubbed because “they’re just kids”.

Hands-On Training

Through one of Instagram’s programmes, Counter Speech Fellowship, teenagers from urban India get to interact with politicians — like BJP’s Poonam Mahajan and Shashi Tharoor from the Congress party — and get to run their Instagram accounts for a day to spread their message of positive advocacy to a wider audience.

“A lot of issues teenagers face are not on influencers’ or policymakers’ radar. We bridge the gap between the two and guide teenagers on how to bring up their issues like online bullying with policymakers,” says Aparajita Bharti, cofounder of Young Leaders for Active Citizenship (YLAC), a Delhi-based organisation that conducts this three-month free fellowship for a batch of 30-40 teens in eight cities in India and in Kathmandu. These include New Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Guwahati, Chennai and Ahmedabad.

In the last three years, over 400 teenagers across India and Nepal have uploaded close to 7,000 posts on positive advocacy, garnering a following of 65,000 users. “Their content has reached over 35 million Instagrammers,” said Bedi from Instagram India.

For 15-year-old Arunav Ghosh from Kolkata, these numbers are very encouraging. “In school and college, caring about anything was considered uncool. It chips away at your desire to do something meaningful about the issues you deeply care about,” he says.

Post his fellowship stint in 2019, Ghosh has been able to use Instagram to talk about issues like domestic violence and sexual harassment at home by converting information into eye-catching graphics and incorporating his knack for poetry in captions. He even managed to raise funds to donate in May 2020 when Amphan cyclone hit West Bengal, severely damaging areas in his neighbourhood in Kolkata. “Earlier I felt frustrated if my friends couldn’t care about political and societal issues. Now I actively strike up conversations, including talking about menstrual cups with my female friends.”

In Nepal’s Kathmandu city, Saramsha Pokhrel, 17, has just concluded her Counter Speech Fellowship in June. Learning a few tricks about using videos to create an impact, he recently created one to spread awareness on schizophrenia in Nepal. “I saw it in my YouTube recommendations recently,” says a chuffed Pokhrel. Untouchability is another big issue in Nepal and he plans to address that through audio-visual content next. “I think this is the best way to spent time during this lockdown. I’m able to explore myself and think of how best to portray issues through content.”

Back home in Mumbai, 18-year-old Divija Samria is harnessing all the lessons learnt during her fellowship while dealing with haters on her Instagram account. “I now counter it by understanding where they’re coming from as opposed to thinking “how dare they say this”. I try to discuss and not debate,” she says.

Siddhant Talwar, 19, did his Counter Speech Fellowship with YLAC in Delhi two years ago. “We met people with different ideologies, some even had misogynistic views. It taught me how to foster conversations even in an environment of resistance,” he says.

Tackling opposing views is just one part of the battle. In matters of public policy, for instance, their training also involves how to communicate with policymakers. “Government officials speak a different language so you can’t talk to them like you would to your school or college principal,” says Mohapatra of YP Foundation. “You often can’t, for instance, use the “S” word while talking about sex education or they’ll cringe. Many refer to it as “life-skills education”. We also tell the teens to tone down their language and avoid passionately disagreeing with policymakers at once.”

Speaking of sex-education, through another programme called Unlabel India, several college students have shared stories of sexual harassment and sexual identity crisis in conversations with Yuvaa.

Based in Mumbai, Yuvaa is a youth-centric media, research and impact firm that organised a roadshow to visit hundreds of colleges across 40 Indian cities in collaboration with Instagram last year. “Thousands of these stories have made it to our Instagram page which has helped these teenagers find support for their stories online,” says cofounder Nikhil Taneja. “Across these colleges, we asked students to write a message of kindness for a stranger that we would pass along to a different college on our next trip. As of date, 5,000 such postcards of kindness have found a receiver across the country,” he adds.

While appreciative of these efforts, some teenagers highlight why they were needed in the first place.

“The platform is far from perfect,” says Talwar, who identifies as genderqueer, a term used to refer to people who don’t subscribe to gender norms.

“In the past, one of my posts has been flagged for showing skin and my account was taken down thereafter,” says Talwar, who attributes this to algorithmic racism, but adds that he has seen instances of algorithm racism against brown queer creators go down significantly over the last couple of years.

He now runs an Instagram page called ‘Mardaangi’, which brings out stories of toxic masculinity and male victims of sexual assault, and shares content on navigating sex education as a teenager in the current times. It has over 4,000 followers at present. “Earlier, I wanted to make a change to the world but never thought I had the authority or the tools. I was just a stupid 17-year-old,” he says.

Taneja, meanwhile, is overwhelmed at the impact that sharing stories have generated among a section of Indian youth. During his visit to a college in Ahmedabad, a boy spoke about his bisexuality in front of his class for the first time. He said he had been abandoned by his family when he tried to confide in them. When his story went live on Yuvaa’s Instagram account, he received overwhelming support from both the LGBTQIA community and folks who were learning more about gender diversity. He collated all the comments in a scrapbook and took it to his parents. “You were worried about what people will say, right?” he recalled. “See, this is what people are saying,” he said.

Soon after, the college student’s mother moved in with him to support her son.

(Illustrations By Rahul Awasthi)

Leave a Reply