A virus has upended the world as we know it. It has emptied out entire cities. It has cleared out schools and shopping places. It has transformed the way we live and work. Now, will it change what we have always believed is the unchangeable feature of Indian democracy: how its Parliament, the supreme law-making body of the land, functions? Will parliamentarians attend remotely for the first time ever instead of huddling in Sansad Bhavan?

The budget session ended abruptly on March 23, 11 days ahead of schedule, due to the looming Covid-19 threat. According to rules, there should not be a gap of more than six months between two parliament sessions, which means the next session can be convened on September 23.

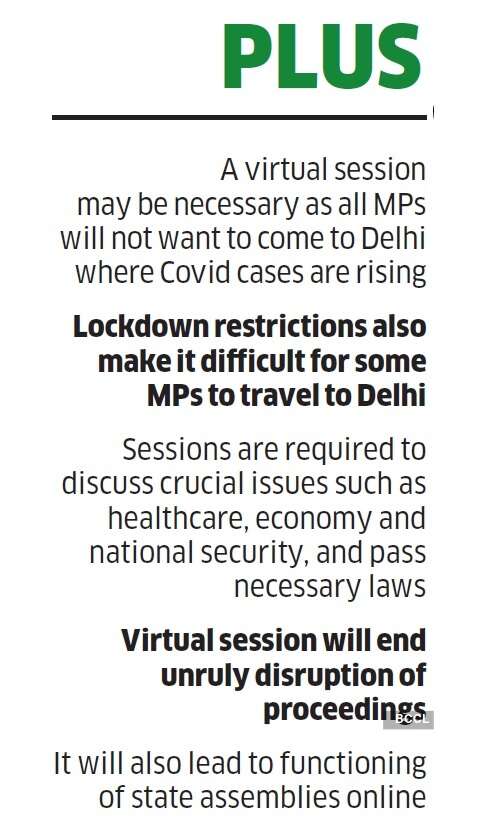

The Opposition, however, has asked the government to stick to the calendar and hold the monsoon session in the last week of July, as the country is facing challenges on multiple fronts: the pandemic, which has created an unprecedented twinning of health and financial crises, and the grave confrontation with China in the Galwan valley, with economic and strategic ramifications. A prolonged absence of House proceedings does away with the legislature’s checks on and oversight of the executive.

Meanwhile, several MPs have expressed their inability to come to Delhi, where Covid-19 cases are touching 1 lakh.

The government is now mulling the option of holding a virtual session or a hybrid session where some lawmakers are physically present while others join online. For a fully virtual Parliament session, arrangements will have to be made by the National Informatics Centre to connect 542 Lok Sabha members as well as 242 Rajya Sabha MPs through video-conferencing.

Even a hybrid session of the Lower House — with half of the members seated in Vigyan Bhawan, Central Hall and the Lok Sabha chamber, following social distancing norms, and the rest connected online — will be an extraordinary technological challenge.

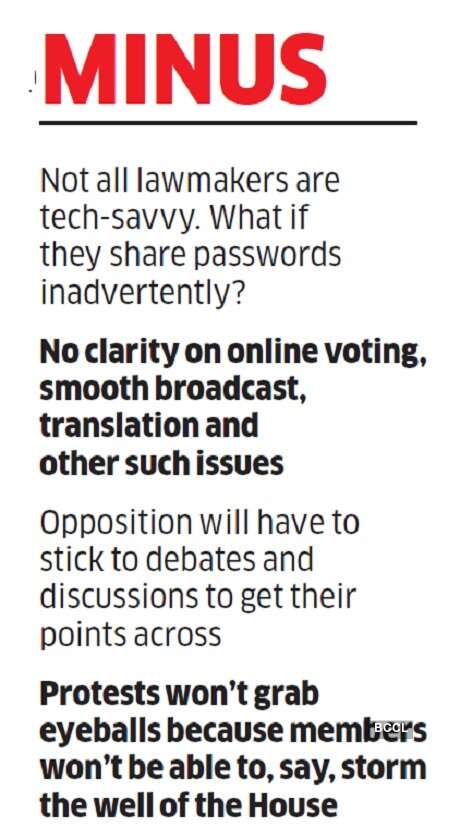

While supreme powers are vested in Parliament, there should be uninterrupted power supply and a secure broadband connection wherever parliamentarians are located, including in remote parts of the country, to ensure that they take part in virtual proceedings securely and uninterruptedly. While UK’s House of Commons, that has gone for a hybrid sitting, is using Zoom, which is unlikely to be accepted as a platform in India.

About two dozen countries, including the US, Germany, France, Australia, Argentina, Brazil and Denmark, are holding virtual sessions. In the US, Senate panels have gone for virtual hearings. Before Indian Parliament goes virtual, there has to be clarity on online procedures and a few mock sessions. The first question will be about the quorum itself: Will it be enough if one-tenth of members log in? Are all members tech-savvy to effectively participate in a virtual session?

In an e-Parliament, the chair will have a tough job keeping an eye on all members to ascertain who wants to intervene or speak. Will the chair need to scan multiple screens for that? Will the assistance of the staff be required? Will there be a buzzer system where the first member pressing the button will get the chance to speak? There are enough queries to fill a few Question Hours.

Another big challenge in India will be in translating the proceedings in real time for everyone who is connected online. Even for those physically present, Vigyan Bhawan and Central Hall do not have access to the translation facility available in the two chambers of Parliament.

If Parliament moves on to conducting other businesses of the House, like passing legislation, too, virtually, it will bring in a fresh set of challenges on how to conduct voting and prevent hacking.

Virtual Parliament will also fundamentally change how the Opposition opposes in the House. The Opposition MPs will not be able to force adjournments or cause disruptions by rushing into the well of the House, holding placards, interrupting speakers, shouting slogans, or staging a walkout. “We will be encountering a new normal as walking out of the House or walking into the well will not be possible. Any protest or attempt to disrupt could be controlled remotely,” says Bhartruhari Mahtab, BJD MP from Cuttack.

In the absence of aggressive tactics, the Opposition will have to bank on effective debates to put their points across. It would be difficult to enforce a washout of a virtual or a hybrid Parliament session, but the Opposition’s main worry will be whether an enforced orderliness online will be perceived as a lack of aggression on their part and give the government a leg up in the proceedings.

SP’s Rajya Sabha MP Javed Ali Khan describes this as an “odd situation” where the Opposition may have to think of innovative ways of protest. “New ways of protest may be found. If some members are physically present (in a hybrid sitting), they can register a protest. As for forcing adjournments, let us first wait and see in what form the session is held,” he says.

If virtual becomes the new reality in Parliament, it will give a signal for state assemblies and councils across the country to go online.

Leave a Reply