Executive Summary

When it comes to connecting with strangers in a new relationship, our minds often jump to associating them with a friend or family member who we know well (“you remind me of so-and-so!”)… something we do without even realizing it. The tendency to do this is part of our brain’s natural shortcuts to making sense of the world; if we can associate someone new as being ‘similar’ to someone we already know, it becomes easier to figure out how to interact with and relate to them. Yet while this is often helpful and poses no problems, in some cases our tendency to substitute in another existing relationship can be counterproductive, blinding us to really taking the time to understand the person in front of us, or even causing adverse reactions when it turns out the person we’re actually relating to is not like the one our brains are associating them with! And this is especially relevant for financial advisors and their clients, where failing to really understand the person in front of us can impair the relationship between the advisor and client, and undermine the open lines of communication that are so important to ensure that the advisor is able to obtain the information needed to provide the necessary advice (and deliver it in a way that the client will actually implement it!).

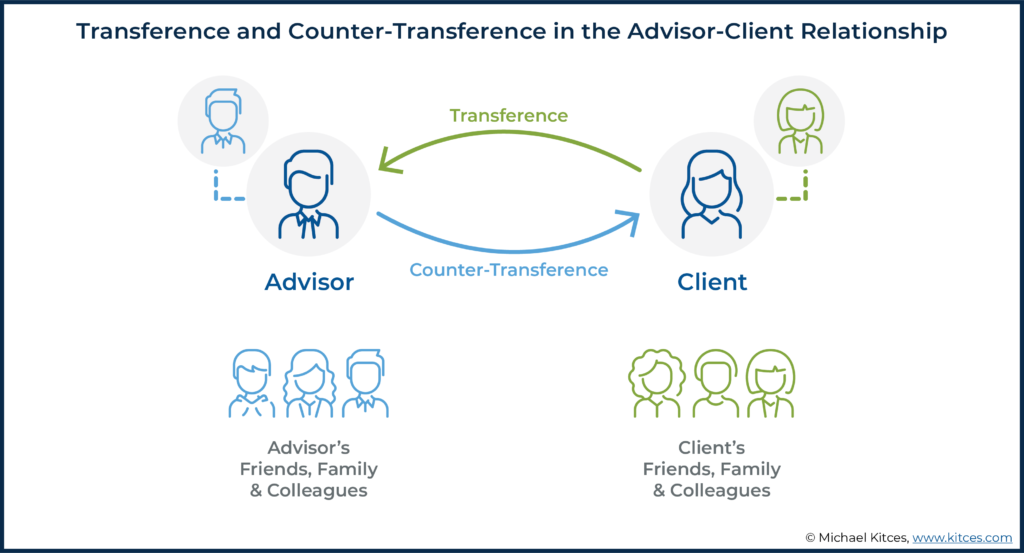

Drawing from the world of therapy and mental health, this phenomenon of a patient projecting the values and characteristics of someone with whom they are very familiar onto the professional they have engaged, but don’t yet know very well, is referred to as “transference”. Similarly, the professional projecting values of someone else onto their patient is referred to as “counter-transference.” For example, a therapist may remind a new patient of the patient’s own brother. If the patient has had a supportive and caring relationship with their brother, they may immediately feel an unfounded trust for their new therapist, based on how the patient feels about the brother. Alternately, if a patient reminds their therapist of an intensely disliked relative with whom they are always fighting, they may experience counter-transference issues and may find it difficult to empathize with compassion toward their patient. And, like therapists and their patients, financial advisors and their clients are just as prone to engaging in transference and counter-transference behaviors during their relationship.

For instance, when difficult relationships (not with the advisor) in a client’s life remind the client of their advisor, unhealthy transference tendencies can cause the client to have trouble communicating openly with their advisor about important financial affairs, or make them unwilling to accept the advisor’s advice. Similarly, problems can arise for advisors if a client were to remind them subconsciously of a person with whom the advisor has an unhealthy relationship, such as the advisor who struggles to give hard advice to an elderly client that reminds them of their own mother. This difficulty to communicate becomes problematic, not only because it can prevent information crucial to the financial planning engagement from being shared, but can also eventually lead to feelings of frustration and burnout – for both advisor and client.

To address the situation and prevent counter-transference-based tendencies from harming relationships with clients, advisors can use various techniques to practice awareness of any counter-transference behaviors they may be impacted by. As a first step, advisors can identify any of their own personal triggers that may be impacting their client relationships. Recognizing and understanding the differences between the client and the other person being mentally associated with the client, who may be the actual cause of the advisor’s personal triggers, can be helpful for the advisor to see the client clearly as the unique individual that they are. A self-analysis tool that can be helpful for the advisor to work through counter-transference issues is the Money Script Inventory, which helps to identify subconscious beliefs about money (which can itself be a springboard for further investigation into the actual causes of those beliefs, which can often provide clues to identify counter-transference causes). Another technique is for the advisor to assess their own money history by reflecting on their own personal relationship with money and the challenges they have faced around money.

While self-analysis can be sufficient for some advisors to work through counter-transference issues, others may prefer the support and guidance of a mental health professional themselves. Therapists understand and know how to help their patients work through transference issues, and are themselves trained to work through their own counter-transference habits.

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors have access to tools that can help them recognize their own counter-transference tendencies, which can help them maintain healthy relationships with their clients, and that are key to open communication and good financial planning!

How Transference And Counter-Transference Are Used By Financial Advisors And Clients To Categorize Relationships By Association To Others

Transference and counter-transference are terms that come from the world of therapy and psychology, and describe one way that human brains categorize new information pertaining to relationships, in which an individual associates a newer relationship with old or familiar information.

For instance, financial advisors are probably very familiar with mental accounting – the way clients categorize money in order to make decisions simpler and faster, even if it is not always in their best interest. In turn, we also tend to apply transference to categorize people, almost always unconsciously, which can make the process of getting to know someone simpler and faster.

Example 1: Tim and Sarah recently met and have become fast friends. Tim reminds Sarah a lot of her brother, Bob, and Sarah and her brother Bob are very close.

Sarah may feel, in part, closer to Tim because of the feeling and thoughts that Sarah transfers onto Tim from her relationship with Bob.

Specifically, in a patient-therapist relationship, transference is how the patient associates their therapist with someone other than the therapist, by ‘transferring’ aspects of that other person’s identity on to the therapist.

For example, a patient may associate their therapist with her mother. In a meeting between the therapist and the patient, the patient worries that the therapist may think that they are needy if she asks to attend meetings more often, as when the patient was a young child, her own mother often accused her of being emotionally needy. The therapist likely does not think the client is needy and may even think more meetings would be great. Yet, the client, because of the transference, may not ask for more meetings because she is fearful that the therapist will view her like her mother viewed her – needy.

Similarly, transference can (and often does!) take place in a client-advisor relationship. For instance, if the advisor reminds the client of their father, or perhaps a spouse, they may, in turn, relate to their advisor in similar ways that they relate to that reminded-of family member.

While this may not have negative implications on the client-advisor relationship if the client had a healthy, trusting relationship with their father or spouse, but it isn’t so great if that wasn’t the case.

Example 2a: Lydia’s father always told her that he felt she was careless with money. Lydia is meeting with her financial advisor, Bob, who reminds her of her father.

During the meeting, they are having a conversation about new budgets, and Lydia feels emotionally flooded as Bob suggests that she cut down on some of her expenses.

Lydia fears that her advisor Bob is judging her spending habits, too, the way her father always did, and that he will also think Lydia is careless with money.

Example 2b: Donna’s late husband always managed their finances and made her feel very safe when it came to money.

Donna, now sitting across the table from her financial advisor, Luke, is having a conversation about portfolio withdrawals, and thinks of how much Luke sounds like her late husband talking about finances.

Donna feels pretty calm and very safe about her financial future because someone like Luke is in charge.

On the flip side of transference is counter-transference, which is how the therapist (or advisor) relates to their patient (clients). And similar to transference (only in reverse), the advisor associates the client with someone other than the client by ‘transferring’ aspects of their own other relationships onto the client.

For instance, perhaps a client reminds the advisor of a grandparent or a close friend. Again, this may not turn out to affect the client-advisor relationship negatively (grandmothers and friends are generally pretty wonderful!), yet it can certainly color the way we perhaps share (or don’t share) information.

Example 3: Gordon, 57, is the financial advisor to Hellen, 92. Hellen is the same age as Gordon’s own mother, and Hellen actually reminds Gordon a bit of his mom when he thinks about it.

Gordon recognizes that this is why he has been putting off calling Hellen to talk about her estate plan; he does not have good news, and hurting Hellen by having a hard conversation about death feels about as awful as hurting and facing the mortality of his own mom.

In Example 3 above, Gordon recognized that he felt bad about needing to call Hellen because it reminded him of telling his mom bad news, even though Hellen isn’t really his mom, but his client. What is more, counter-transference might even change the way we deliver information.

Example 4: Hellen, Gordon’s elderly client, has been spending a bit erratically. She has been giving a lot of money to her grandkids and friends lately – much more than she normally does.

Gordon decides to call and find out what is going on. Once he is on the phone with Hellen, instead of taking a harder stance about the spending, Gordon lets it all slide under the rug.

Talking with Hellen reminds Gordon too much of talking with his own mother, and he realizes he cannot tell either one of them ‘no’ – which is what Hellen actually needed to hear!

In Example 4, Gordon’s underlying connection between his mother and Hellen is prohibiting him from giving Hellen the advice that she really needed to hear – that she can’t just keep giving away her money – but he could not say ‘no’. Just as he would not have said ‘no’ to his mom.

The significance of transference and counter-transference in the advisor context, though, is that financial advisors are not taught that these concepts/behaviors even exist (let alone how to handle them). Even though it is probably often a larger part of their work than they realize, because of how advisors typically work with their clients.

For instance, finding a niche to specialize in can be a great thing, but consider the following example.

Example 5: John became interested in working with doctors because his father is a doctor. Therefore, John understands the life of the doctor, and some of the personal and business challenges they face.

Yet, John did not necessarily think about the fact that, although he really respects his dad’s work, his dad worked really long hours and that because of the work schedule, John missed his dad a lot when he was younger.

Fast forward 25 years, and John is now giving ‘unbiased’ advice to 30 people that remind him of his father!

In a recent meeting with a new doctor client, John and the doctor were discussing plans to open a new clinic. John was comfortable discussing the numbers and agreed, on paper, that it made sense. During this meeting, though, John also spent a lot of time talking about and reminding the doctor of what opening the clinic could do to his home life. John never crossed the line and said the doctor should not go for it, but John recognized he was pushing back and maybe taking the plans a bit too personally.

Counter-transference is not necessarily limited to those advisors using a niche. Many advisors have the luxury of choosing to work only with clients who they like personally; some financial advisors are even advisors to their friends. If this is the case, will your other clients who came as referrals from one friend also remind you of that friend?

And, similar to Gordon and Hellen in Examples 3 and 4, might counter-transference impact your ability to dispense advice in the best interest of your client? Remember, Gordon could not say ‘no’ to Hellen, even though it was what she needed to hear. It is not unthinkable that an advisor who feels they are friends with their clients may really struggle to give the advice that the client needs to hear.

Moreover, as discussed in the next section, advisors may actually bring more opportunity for transference and counter-transference to impact their relationships simply by the way they choose to build their client base or plan out their client work.

How Transference And Counter-Transference May Impact Advisor-Client Relationships – What Advisors Should Know To Protect Themselves From Burnout And Giving Inappropriate Advice

As exemplified in the prior section, when clients or advisors associate each other with an unrelated person, transference and counter-transference that ties the traits and aspects of that unrelated third party onto the advisor or client can have the potential to break down advisor-client communication, especially when the associated relationship was unhealthy or unpleasant.

For instance, in Example 4 above, Gordon was unable to tell his client Hellen, who reminded him of his mother, what she really needed to hear, essentially acting out the conversation as though it was with his mother (who he wanted to protect and not have hard conversations with).

Said another way, communication breaks down under these conditions because, instead of talking to or giving advice to the actual individual, the advisor or the client is really acting out a conversation with an archetype or template of someone else.

Example 6: Lydia is meeting with her financial advisor Bob to talk about her budget. She can’t help but think of her dad, who often accused her of being careless with money.

As they review Lydia’s budget, Lydia notes that she likes to treat herself to 3-4 nice vacations a year. Bob suggests that Lydia could reduce her expenses by cutting back on her traveling expenses, and asks Lydia to consider a ‘stay-cation’ for one of her outings instead, to save a little more toward one of her other goals.

Lydia recoils at this suggestion and says, “Why would you even consider that? My vacations are important to me. You think my vacations are frivolous, don’t you?”

Bob, a bit stunned, responds, “No, I did not think that at all. I know you work hard and deserve your vacations.”

Lydia replies, still angry, “I do work really hard, and I do well for myself. I am not flippant about my spending decisions!”

Bob, “I hear you saying that a lot of these expenses are rewards for your hard work, and I don’t want to take that away from you. Please let me know if there is something else on this list that you would feel comfortable removing. If not, let’s go back to the drawing board together – I want to set up something that works for you.”

Bob realizes that he has clearly hit a nerve with Lydia, but has no idea why or where it came from. He has no idea that Lydia is experiencing feelings and emotions based on her relationship with her father, and that friction point with Lydia’s father about her spending habits is now being transferred onto the conversation with Bob. He just knows he is receiving push back and instead of getting frustrated, he pulls back. This isn’t the first time he has experienced pushback like this from Lydia – working with her is often a bit difficult… not coincidentally, just as Lydia’s relationship with her father was.

Bob may become burned out over time in his relationship with Lydia. Or even worse, the relationship with Lydia might further deteriorate to the point where Lydia actively resists any of the suggestions Bob makes related to her plan, mirroring a similar unfortunate deterioration that Lydia had in her relationship with her father over time. And the important thing is, it isn’t Bob’s fault!

Bob cares about Lydia and is not sure what went so wrong, but it can also be legally unsafe to keep a client that outright refuses and maybe even reacts in rebellion to a proposed plan.

Moreover, while the example of Bob and Lydia may be extreme, it is not uncommon to have clients react in perhaps odd ways to the advice given; this may be related to a client transferring and acting out repressed emotions of a past relationship onto the relationship with their advisor.

However, just as telling clients they’re behaving ‘irrationally’ due to cognitive biases is not actually a good way to help them change their behavior for the better, it is not advisable for the advisor to just blindly probe the issue to figure out what is happening (e.g., Bob saying to Lydia, “I think that perhaps you are acting out past issues with your father when you do not follow my financial advice” or anything like it!). Transference is one of those things that, although advisors are going to see it and likely be impacted by it, takes serious therapeutic skill to confront.

Moreover, if this is happening (e.g., getting strong pushback from a client), consider making a mental health referral. There very well may be, as is the case with the average person, a lot of emotional stuff the client needs to work out regarding their money and a therapist’s office is often the best place to work through that stuff – not necessarily the advisors’ office.

Nerd Note:

Giving a referral does not have to be difficult! Check out our blog article on when and how to give a referral and start implementing a mental health referral practice now. For instance, COVID-19 is a great reason to suggest that all clients talk to someone. Use this time to implement a non-biased, broadly advertised mental health referral practice.

Also, although not a great answer, please recognize that sometimes, it is enough that the advisor is simply aware of the possibility that this could be the reason a client displays surprising behavior, and can rest easier (and hopefully avoid burnout) when a client doesn’t listen (or when the client actively goes against the plan). Basically, sometimes it is not you… it is them.

But… there can also be times when it is you!

As while it sounds simple, advisors must see their clients as the individuals who they are, not as someone else who might remind them of the client, in order to serve them properly.

There is nothing wrong with seeing similarities between a client and someone else from your life, but it is important to draw the line between seeing the similarities, and – potentially unwittingly – acting on them by allowing counter-transference to affect the relationship.

In fact, to combat this, highlighting in the advisor’s mind the differences between the client and the other person may be helpful for the advisor to maintain a view of the client as their own unique individual.

Example 7: Gordon is a financial advisor and regularly reads the Kitces blog. He learned about Transference and Counter-Transference from a recent article and recognizes immediately this is what he sometimes does with his elderly client, Hellen, who reminds Gordon of his mother.

As such, to stop this from affecting the relationship and the advice he gives to Hellen, Gordon gets out a pen and paper and makes a list of all of the ways in which Hellen is nothing like his mom.

Gordon can make an active decision to bring the unconscious association he has made between his client and mother into his conscious awareness. By doing so, he will actually find it easier to deliver advice truly in Hellen’s best interest and not let it be overshadowed by the advice he may (or may not) have given his mother in a similar situation.

Gordon, in Example 7 above, was quickly able to put two-and-two together. Yet, it is not always that simple in practice. In fact, it can also look like Lydia and Bob in reverse. As we will discuss, advisors too (and I think possibly commonly) will act out their own unfinished business, similar to that of Lydia acting out her own unfinished business with her father, with Bob her advisor. Acting out unfinished business does not necessarily translate to harming the client, but it is absolutely something to be aware of and own.

Moreover, the bigger point is that if you find you are holding back advice, changing advice, or running into a wall with your advice, it might be due to how you are relating to the client at a subconscious level.

And notably, we all do it; it is totally normal for transference and counter-transference to happen (again, it’s part of how our brains are wired to deal efficiently with the world in the first place!). However, when we are not aware of it, it can have more control over our behavior (and the effectiveness of the advice we give) than we would really want.

Practicing Awareness Of Counter-Transference Effects Can Help Advisors Improve Client Relationships

Similar to the advice for clients to find a therapist to work out deeper emotional and relational issues played out in the advisor’s office, advisors, too, will want to work out their own emotional and relational issues. And advisors can start by working to bring their own, perhaps currently unconscious, counter-transference to the surface.

A big first step for advisors is to understand their personal triggers and where they come from. Knowing your triggers will help you understand why certain client relationships may be more challenging or more fun, while others are the exact opposite.

For instance, in Example 5, above, John’s chosen niche included doctor clients because he was familiar with his father’s work as a doctor. Furthermore, John remembers missing his father a lot in his youth because of his father’s long work hours. Thus, John sometimes inadvertently gives advice to doctors that places a disproportionate emphasis on the importance of family. John is working out his own unfinished business in his relationship with clients.

Now, not that family isn’t important, but John is not doing this because the client asked for such advice about how to prioritize more time with family. Rather, John is giving this advice because of his experience with his own father when he was younger – which means the family advice may not necessarily be relevant to the client’s situation, nor in their best interest. John isn’t seeing the client objectively.

And John is just one example. In my work with advisors, I do not know how many times I have personally heard stories about a tough financial situation in childhood, a tough divorce, or how they knew someone who received bad financial advice and, as such, they have vowed to right that wrong.

Furthermore, these stories and connections are not bad, per se. They brought you to where you are today. However, not realizing or understanding the impact of the past playing out in real-time may certainly, as we have seen in many examples, impact the advice given (and not).

Counter-Transference Self-Analysis Tools For Advisors

A great place to work out counter-transference issues is in therapy, as this is actually what therapists work on! As part of a therapist’s work to become a therapist (and even ongoing if they are working with a client that perhaps confuses them or they find challenging), they are required to work with another therapist to confront their own counter-transference habits. And advisors can do the same!

Consider the following. John, from Example 5, recognizes that his past colors the advice that he gives and that sometimes, when he gets home after a long day of meetings, he feels emotionally worn out. He decides to see a therapist. John wants to get to the bottom of the relationship with his father and understand how his past is playing out in the present with clients. Moreover, after making a few phone calls and talking with a few therapists about their specialities, he makes an appointment with someone he feels can help him and he feels he can talk to and open up with about his life. John meets with the therapist every other week for an hour. In the beginning, it is a bit awkward, John has never seen a therapist before. Yet, after a couple of sessions John feels they are actually getting into his work, how he sees clients, his father, his home life as a kid – it is all starting to come together. After a few months, John sees things much more clearly and has even worked out with his therapist some ways to help separate the clients from his father (keep reading for some ideas on how to do this yourself). John stops seeing the therapist at regular intervals, but trusts that if a difficult client entered his life that he could call the therapist again to discuss.

However, if meeting with your own therapist doesn’t sound like something you want to try, that is perfectly okay. There are other options that don’t involve seeing a therapist, such as simply taking the time on your own to explore how you feel before and after client calls and meetings. Which clients get your heart-racing, which clients put you at ease? And why do you think you feel that way with those particular clients?

Now, while even this might all sound a bit ‘different’, consider this. Advisors cannot control their clients, but they can control how they let their clients impact them. And if advisors understand what it is that is eating at them, they have more control over it.

So here are some suggested steps on how advisors can practice their own self-analysis to address their counter-transference issues.

- Explore your subconscious beliefs about money by taking the Money Script Inventory or by reviewing your own Money History.

The Money Script Inventory is a great tool because it can teach advisors about their own subconscious beliefs about money. Advisors can even take this a step further and, after learning their money script, investigate where it came from, learn about their family history, and use that to give greater context to their beliefs.

In order to transform subconscious thoughts into conscious ones, think about what you have learned in your past, who taught it to you, and how those things currently impact your present. This not only builds empathy – we can see how easy it is for clients to do the same thing – it also gives so much more context for the next step in which we actually think about the clients.

So, go ahead. Take 10 minutes and complete the Klontz Money Script Inventory here.

- Review client relationships with new eyes.

Advisors will do well by themselves to sit down and think through the following list of questions.

- Are there current clients that make you feel angry?

- Are there current clients that make you feel stressed?

- Are there current clients that make you feel inadequate?

- Are there current clients that make you feel joy?

- Are there current clients that make you feel excited?

- Are there current clients that make you feel fulfilled?

After you ask yourself these questions, consider how they may relate back to your own personal relationship history. Are you able to come up with any examples as to how these emotions perhaps colored advice you gave or did not give to a client?

- Identify the connections between your personal money beliefs and your client relationships.

Ask yourself what connections there are between your own money history and money beliefs that may be reflected in your client relationships.

Again, the goal of this is to create self-awareness. Advisors may find that they have given advice colored by counter-transference. If this happens, it is okay. It happens all the time subconsciously; now that you are aware of its effect, you can work to make changes.

Example 8: Lilly, a planner, grew up with two parents who were horrible with money and vowed, as an adult herself, to be great with her own money and to help others to be good with theirs, as well.

In going through the Money Script Inventory, she realized she is ‘money vigilant’ and really becomes overwhelmed with anxiety and frustration when she works with clients that do not want to dive into the numbers.

However, she realizes now that this has more to do with her own issues with money than it does with the idea that the clients just don’t care.

Moreover, while this may be a large lift the first time you do it – advisors can start a practice of checking in and regulating in real-time moving forward. This may be done by taking time in between meetings, and maybe even during meetings to check-in briefly with themselves when they feel stressed, overwhelmed, angry, tired, sad, or any one of a host of other emotions.

Once a meeting is over, and the advisor has time to debrief and review the client’s plan, they can also check-in with how they are feeling.

Counter-Transference Check-Ins After Client Meetings

Some questions that you can ask yourself after a client meeting:

- Am I stressed or happy?

- What connections are being made in my mind about the client?

- What did I learn from stopping and thinking about these connections?

- After considering the answers to the questions above, how can I prepare for the next meeting or follow-up with that client?

In addition to the ‘post-meeting’ personal diagnostic, advisors can try checking in with themselves during meetings, as the meeting is really where counter-transference is taking place with the client.

Counter-Transference Check-Ins During Client Meetings

Here are some steps that can be used for check-ins during a client meeting, particularly if you notice anxiety, stress, or other uncomfortable feelings, maybe even sadness, arising in the middle of the meeting:

- Check-in on your breathing:

- Ask yourself, “How is my breathing right now?”

- If it feels faster than normal, ask yourself, “What am I responding to?”

- Check-in with your emotions (but don’t judge them!):

- It is okay to be stressed (just as it is also okay to feel joyful!).

- Acknowledge and accept what you feel; recognizing your feelings without judgment will help you process them in real-time.

- Understanding how we feel in the moment can help us decide how to react (or not react) in order to build trust in the meeting.

Last but not least, consider getting a teammate to join you in meetings. Teammates can help us stay objective and can provide objective advice if we start to counter-transfer. Teammates can also help us check-in after meetings to make sure we didn’t miss anything, and give us feedback about whether we actually delivered objective advice.

Teammates might even offer an opportunity for more self-exploration by actually discussing whether something did come up for you, what it was, and where it came from (assuming, of course, that you and your teammate are both comfortable doing so).

Recognizing Differences Between Clients And Associated Archetypes

If you cannot work in a team, another practice that advisors can use to stay objective is to recognize differences between clients and the person or archetype that you may be associating the client with – which may not be perfectly easy to do.

It is not always easy to uncover the unconscious when it comes to the way that counter-transference may be showing up in advisor-client relationships; however, the following two steps can provide guidance.

- Ask yourself, “Who does this client remind me of?”

- Going through your own money scripts and money stories will help you cultivate awareness of your own triggers and will give you a clear idea of why certain clients get to you.

- Start thinking about how your client not like X. (e.g., How are they not like your grandmother? How are they not like your parents?)

Learning to separate the client from others who we have associated them with helps us to individualize the client. This does not necessarily cause the effects of counter-transference to cease altogether, but it can be a good way to alleviate some of the issues.

Transference and counter-transference are required subjects studied in therapy and psychology, but they are not taught to advisors. Yet, there are many similarities between the relationships that advisors have with their clients and those that therapists have with their patients. Advisors, like therapists, guide and support their clients through change, work toward goals, and enter into very personal aspects of the client relationship. And because financial advice, like therapy, is so relationship-based, financial advisors can also benefit from understanding the effects of transference and counter-transference that show up in professional-client relationships, and what they may do to one’s ability to communicate actionable advice to clients.

And in the end it’s important to recognize that while advisors can’t change their clients, they can change themselves. Even relatively ‘simple’ things, like being aware of how certain clients may be more or less easy to work with and reflecting on why (and how counter-transference may be playing a role) are valuable. Though ideally, advisors who really want to strengthen their advisor-client relationships will decide to go deeper and actually set out, like therapists are trained to do to better work with clients and communicate, to do their own internal work to bring the subconscious conscious so it doesn’t accidentally cloud their advice and their advisor-client relationship!

Leave a Reply