Working as a financial planner all of my adult life — the first 20 years as a corporate financial planner and the second half working with individuals — I’ve seen some big changes in the industry, some foreseeable and others, many in fact, that have been so counterintuitive or just plain out of left field that they shocked me.

Below I’m sharing my top seven top surprises in hopes that being forearmed will give my fellow advisors the edge in building your practice and in helping your clients attain their financial goals.

1. Pessimists prevail

Some clients are extremely optimistic about their financial situation while others are certain they’ll never have the funds they will need to retire. To my surprise, it was those clients who believed they were in great shape who were generally in far worse shape than the fatalistic ones.

In hindsight, this makes perfect sense. The optimists have gone through life thinking things will take care of themselves and so never learned to defer immediate gratification. Pessimists feel more pain from an active insula — the part of our brain that gives unpleasant feedback such as the pain of paying — when spending money and are deathly afraid of ending up living under a bridge.

These two types would be exemplified by a 63-year-old doctor earning high six figures with a net worth of about $200,000 who thought he was in great shape as opposed to a client worth $10 million living a frugal lifestyle thinking he’d never be able to retire.

The lesson here is to give the frugal saver client some validation that their pessimism led to building wealth and, if appropriate, teach them that dying the richest person in the graveyard is a lousy goal and that they should enjoy their money to do whatever brings them happiness. For those that need to cut back, have them go through some exercises of tracking expenses and getting feedback on how much they are spending.

2. Those that are the surest of their behavior are the most wrong.

I’m not a fan of risk profile questionnaires but to engage a new client on behavior, I do ask what they would do if their stock portfolio lost 50%. The vast majority say they would rebalance and buy more stocks. But some say something like, “Of course I would buy more stocks because they are on sale,” while others say “I hope I’d be able to buy more stocks — I know it will be very painful.”

In market plunges, including the brief Covid plunge in March, I spent the most time talking to those clients who were sure they would buy more stocks off a cliff to prevent them from panic selling. Buying more stocks to rebalance was off the table.

These clients hadn’t thought through the pain they would be feeling when their financial independence was pushed back significantly and often went to protect what was left by selling stocks when they were on sale.

On the other hand, those that said they hoped they could have the courage to buy more stocks actually did. They embraced the pain and followed through.

The lesson here is to push back and let the overconfident client know just how hard it is to buy the asset class that has caused so much pain. If you think we advisors don’t fall prey to poor market timing, think again. Here’s some statistical data on thousands of advisors who as a whole got the timing wrong.

3. Consumers are getting it — indexing grabbed far more market share than I ever imagined

I started indexing in the late 80s. The logic made so much sense to me and I helped the corporations I then worked for invest pension money in index funds and offer low-cost index funds in their 401(k)s. In fact, one key reason I became a personal financial planner is I felt bad for the individual investor’s money being invested so differently than corporate assets — and missing out on higher returns.

When I started my practice in 2002, I had to explain to people what an index fund was and why they bested most active funds with higher fees. Today, there is more money in U.S. stock index funds than active funds. As a result, I can concentrate on analyzing the tax consequences of selling expensive investments to move to low cost and more tax-efficient index funds.

I’m not just surprised, I’m totally shocked, but in a very pleasant way, that consumers are getting it. I give the late Vanguard founder, John C. Bogle, most of the credit. But also journalists like Jason Zweig and Jonathan Clements for reaching millions of people with well-written and compelling logic. Morningstar also deserves kudos for making it easy to compare performance and showing the stronger performance of low-cost index funds.

The lesson is that consumers will eventually understand compelling logic. Sure, there will be more fads based on indexing like smart beta, but those are active strategies with merely an indexing label.

4. Plunging — and now zero — fees

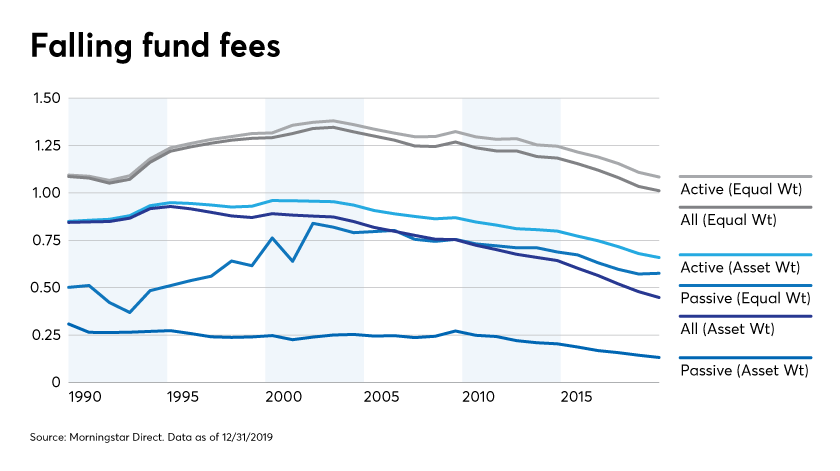

I bought my first stock as a kid and paid a 5% commission. Fund fees had an asset-weighted fee average of 0.87% annually only 20 years ago, according to a Morningstar fee report. Today, zero-cost trades prevail and the fund fees are averaging 0.45% annually on an asset weighted basis.

It isn’t about indexing alone — fees have fallen in active funds as well. But only on an asset- weighted basis, showing that consumers are moving their money from high-cost funds to low- cost. Additionally, fee wars have pushed expense ratios down to 0.03% at Vanguard and to 0% at Fidelity. Because funds return some or all of the profits from securities lending, it can now be argued that, net fees, some funds have slightly negative net cost, meaning investors are being paid to own some funds.

The lesson learned here is that fees matter and clients want low fees. I agree with Morningstar Managing Director Don Phillips that the debate isn’t about active vs. indexing; it’s about high cost vs. low cost funds.

But this is also about more than fund fees or trading commissions: Clients want low fees from their financial planners as well. Make sure you don’t become a commodity as you will lose out to robo advisors. Differentiate yourself by adding value in what is often referred to as advisor’s alpha by doing real planning, improving tax-efficiency, behavioral coaching, and insurance analysis. Then keep your clients in low-cost and diversified investment vehicles.

5. The bond bull market is nearly 40 and real interest rates are negative

Wharton professor Jeremy Seigel believes the bull market for bonds is coming to an end. In 1981, the 10-year Treasury yielded 16% and today, just 0.87%. Falling rates created a raging bull market for bonds that experts have been predicting for years would end.

Now, I’ve long known what a fool’s errand it is to try to predict interest rates so the fact that economists have correctly forecasted the direction of the 10-year T-bond well under 50% — less accurate than a coin toss — isn’t the surprise.

The shocker for me is that bonds are now yielding less than inflation expectations, giving a negative real return. I was taught that there is a time value to money, meaning that one should expect a real positive return, at least before taxes. But now, lending money for a decade is projected to buy less than it can today.

Could we go to negative nominal interest rates? A few years back I would have said no but Europe has proven me wrong. In Germany, long-term nominal interest rates are negative 0.58% annually. For every $100 invested over a decade, expect to get back a tad over $94. This is absolutely counterintuitive. Burying the money in the back yard has a higher return, though perhaps not as safe.

Lessons learned are twofold. First, understand that intermediate to long-term interest rates are unpredictable. If we all knew rates were going up, then when the government has its regular auctions people would bid less for the bonds and rates would have already gone up. But more important is to understand that markets fool us. Yes, negative nominal rates are counterintuitive but markets really don’t care about our intuition.

6. Markets and the economy change drastically

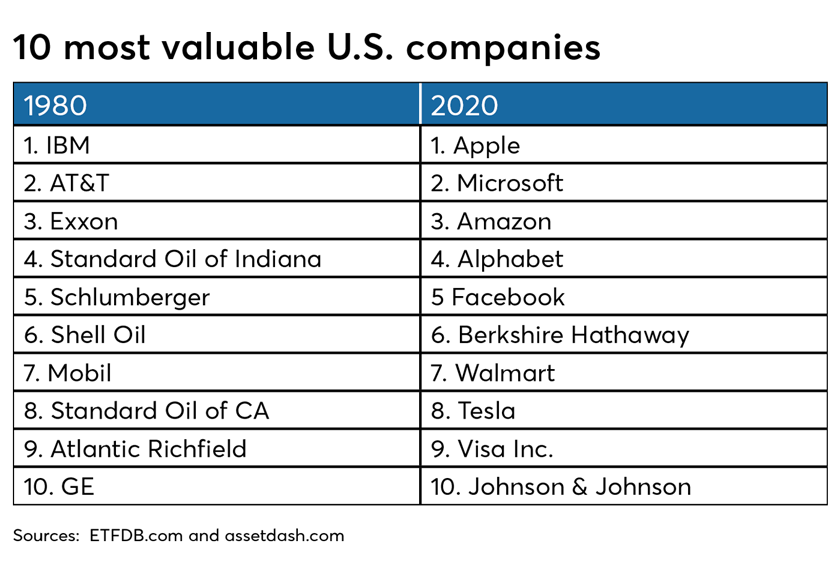

As I was graduating college over 40 years ago, Big Blue, AT&T and the oil industry were the dominant U.S. companies with the largest market cap. Today, not a single top 10 company of four decades ago is on that list. In fact, many of today’s top 10 didn’t exist back then. AT&T was purchased by SBC (which changed the name back to AT&T) and GE is fighting for survival. Tech dominates and energy has suffered.

I really shouldn’t have been surprised. After all, the railroad industry was over half of the U.S. market cap in 1900 and is a rounding error today.

The lesson is to know that radical change is coming and it’s really hard to predict the winners of tomorrow — yet another argument for owning everything according to market capitalization. You can tell your clients that they own the winners and not to buy the argument that a cap-weighted fund overweights those obviously overvalued large cap growth companies.

7. The CFP Board isn’t benefiting the public

This may be my largest single surprise in my decades in the industry. I got my certification thinking the CFP Board would walk the talk when it came to a higher standard and enforcing fiduciary duty. As I have written before in these pages, I was wrong.

My first awakening came in 2008 when I assisted a client in filing a complaint against a CFP who double-dipped selling an annuity, taking both commission and ongoing AUM fees. The CFP board found the client paying 5.29% annually was consistent with fiduciary duty. Even the insurance company and broker-dealer settled, arguably because they had a higher standard.

Sure that’s ancient history but for the next dozen years journalists like Jason Zweig at The Wall Street Journal and Ann Marsh at Financial Planning have written about the CFP board having a lower standard than regulators. The CFP Board looked the other way. Then, last year, a series of articles in The Wall Street Journal including a page one article about the thousands of CFPs with no disclosures by the CFP Board where regulators noted complaints including felony charges.

The stated mission of the CFP Board is to “benefit the public by granting the CFP certification and upholding it as the recognized standard of excellence for competent and ethical personal financial planning.” Did the CFP Board learn a lesson from its massive failures to support the mission? Executive compensation at a nonprofit should be based on fulfilling the mission and last year’s public revelations proved massive failures.

So I asked Jack Brod, the current chair, to disclose CEO Kevin Keller’s 2019 compensation. Even though it must eventually be disclosed when the 2019 IRS form 990 is released, the CFP Board again decided against transparency.

The lesson here: If financial planning is serious about being perceived as a profession, it is up to us to put the client first.

The one constant in financial planning (and just about everything else) is that things will change radically and we will always be surprised. My chief lesson I have to impart: Be humble and embrace change.

Leave a Reply