More than a year after the end of a controversial SEC self-reporting program, a midsize wealth manager that didn’t participate has settled the regulator’s case against it.

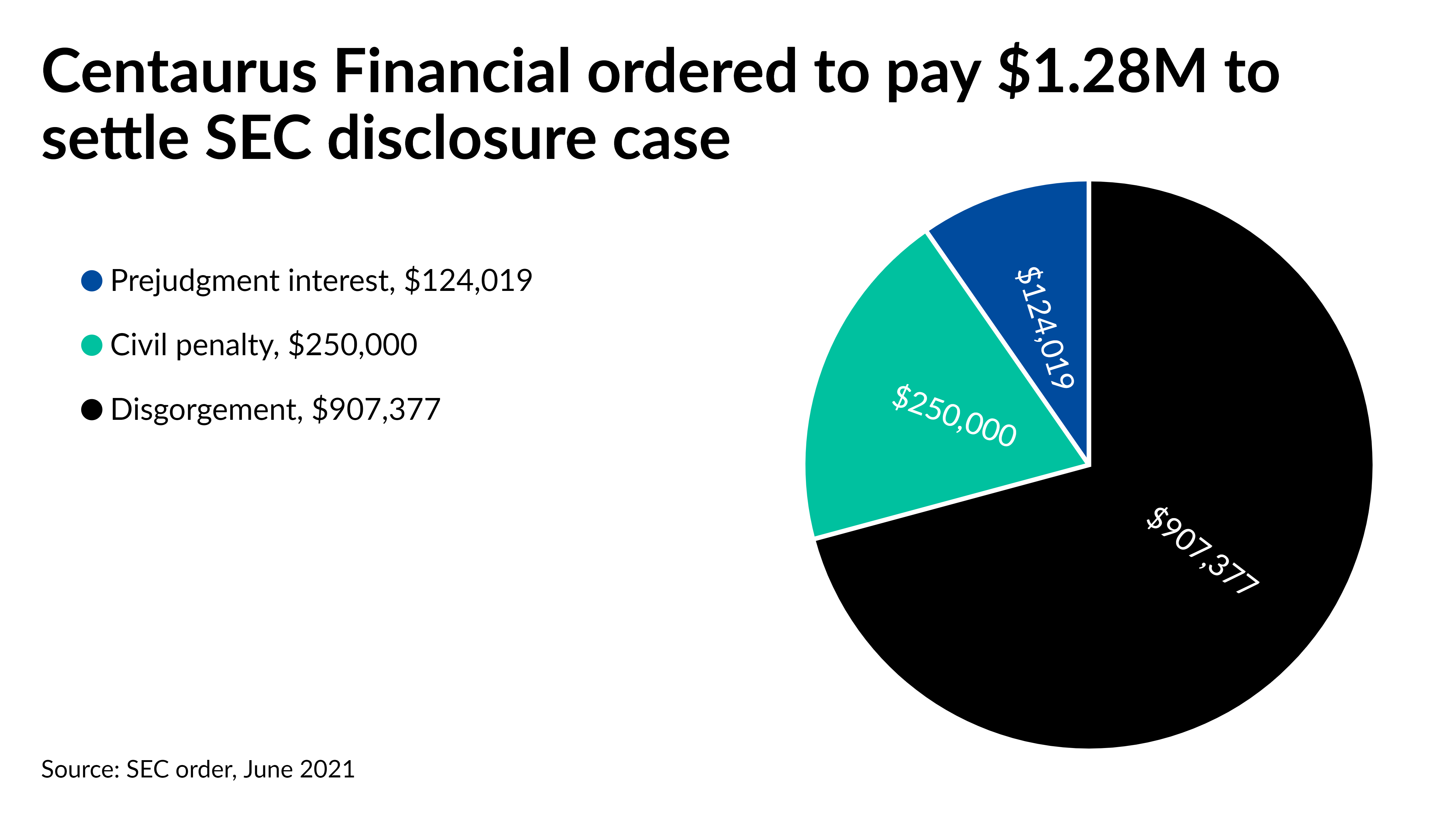

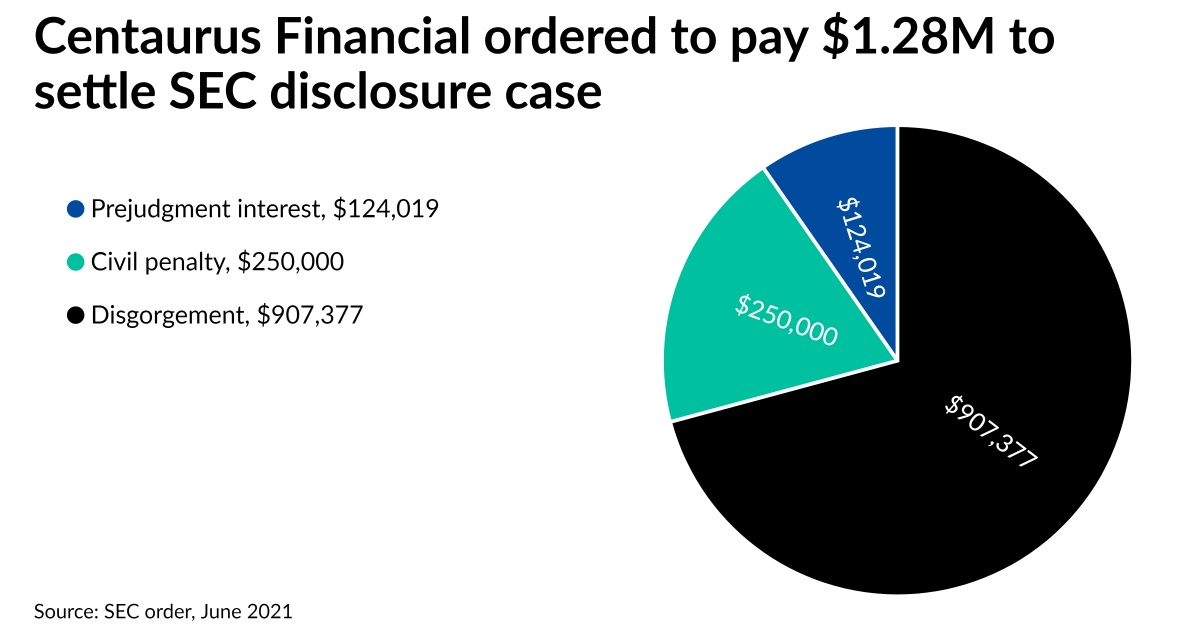

Centaurus Financial agreed to pay $1.3 million in disgorgement, interest and a fine after the SEC alleged the Anaheim, California-based independent broker-dealer failed to adequately disclose conflicts of interest relating to mutual fund 12b-1 fees, no-transaction-fee products and cash sweeps, according to the June 2 order. The SEC’s voluntary share-class disclosure program yielded restitution of $139 million to clients of nearly 100 firms over the past two years.

Although Centaurus is paying much less than many larger wealth managers that did self-report to the SEC, the dispute about what industry trade groups decry as “regulation or rulemaking by enforcement” is being played out in the courts: The SEC has pending cases involving disclosure against Commonwealth Financial Network’s RIA and twoCetera Financial Group firms.

Wealth managers will also be watching recently installed SEC Chairman Gary Gensler’s team closely for an indication of how the Biden administration handles these kinds of enforcement cases, Jennifer Klass, co-chair of Baker McKenzie’s financial regulation and enforcement practice in North America, said in an email.

“The way investment advisers and broker-dealers address conflicts is core to the concept of fiduciary duty (on the investment advisor side) and Regulation Best Interest (on the broker-dealer side),” Klass says. “It will be interesting to see under the new chair how this issue plays out in the context of Reg BI implementation, and how the SEC staff interprets the adequacy of disclosure relating to conflicts of interest.”

She adds that there’s “no question that the SEC will continue to focus on conflicts of interest” in its examinations and enforcement cases.

Just as in the other cases of recent years, the allegations against Centaurus revolve around “its receipt of third-party compensation from client investments without fully and fairly disclosing its conflicts of interest,” according to the SEC’s order.

“In spite of these financial arrangements, CFI provided no disclosure or inadequate disclosure of the multiple conflicts of interest arising from the firm’s receipt of this compensation,” the document states. “CFI, although eligible to do so, did not self-report to the Commission pursuant to the Division of Enforcement’s share class selection disclosure initiative.”

Representatives for Centaurus, which has about $3 billion in assets under management, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The firm cooperated with the investigation, according to the SEC, and the regulator’s settlement took into account “other remedial acts promptly undertaken” by Centaurus in 2018, the year the SEC launched the program. The order doesn’t identify the specific time period of the violations. Other settlements of mutual fund disclosure cases covered roughly a five-year span.

Like other dually registered wealth managers, Centaurus collects payments from fund managers and custodians based on the amount of assets invested in a product or type of accounts. The third-party payments cause certain products or services to cost more or yield less.

The SEC is in the crosshairs when it comes to disclosure cases. Brokerage firms criticize regulators for taking a retroactive view of common industry practices they thought were fully legal, while consumer advocates take the SEC and its Regulation Best Interest to task for requiring mere disclosure of conflicts of interest rather than their outright elimination.

Indeed, the conflicts at issue in the Centaurus case are typical of most brokerages: 12b-1 marketing and distribution fees of 25 to 100 basis points on particular mutual fund share classes and agreements with a custodian to share a percentage of the revenue from NTF products and money market funds with the broker-dealer.

In addition to alleging inadequate disclosure of the 12b-1 fees and a failure to inform clients at all about the NTF and cash sweep conflicts, the SEC says the firm didn’t adopt or implement written procedures designed to prevent violations. Furthermore, the regulator alleged that Centaurus breached its fiduciary duty for best execution of client transactions by causing them to invest in more expensive share classes.

Consumer advocates praise the regulator for adding best execution failures to other fund disclosure cases, like those against Voya Financial Advisors and Prudential Financial’s BD late last year. Industry lawyers, on the other hand, view the provisions as confusing and novel applications of best execution rules, suggesting they could be the next area of debate in the ongoing saga of fiduciary standards.

In an address to the industry at FINRA’s annual conference last month, Gensler reminded wealth managers and other broker-dealers that “best interest means best interest” and “best execution means best execution.”

In its enforcement efforts, the regulator will be “following the facts and the law, wherever they may lead, on behalf of investors and working families,” he said. Reeling off a laundry list of the types of misconduct his team is pursuing, including best execution and fiduciary violations, Gensler put the industry on notice.

“We need to do whatever we can to ensure that bad actors aren’t playing with working families’ savings and that the rules are enforced aggressively and consistently,” he said.

Leave a Reply