What would you say was the most disruptive trend of the 2010’s decade ending today?

The iPhone? Facebook and Twitter? Cloud computing? Okay, they were extremely disruptive, but I’d throw out another trend into the ring – the shale oil boom. For me, it’s been the hidden disruptive trend – the one we don’t talk about as much because investors have not made money as a direct result of it…

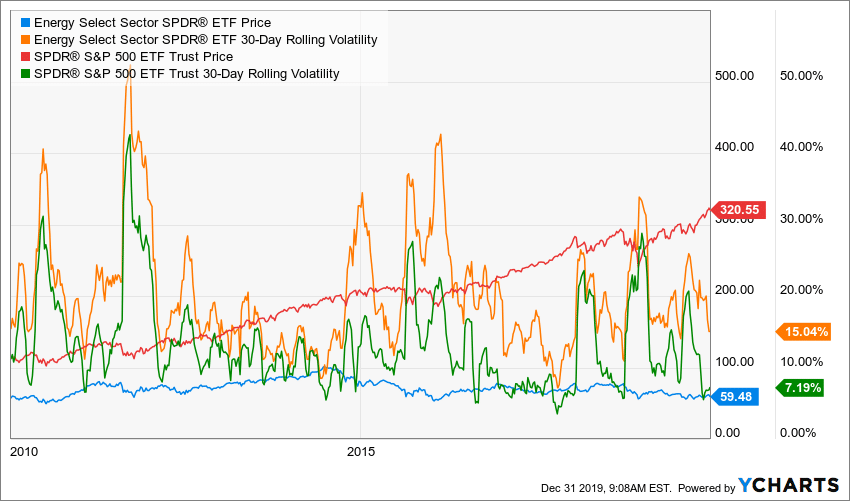

Take a look at the chart above. That’s the growth of $10,000 invested at the start of this decade. The orange line in the S&P 500 ETF (SPY), where every $10,000 invested turned into $28,500 by this week. The blue line is a disaster, that’s $10,000 invested into the XLE ETF, which owns the energy sector of the S&P 500. $10,000 invested barely grew into anything at all, but you certainly got every bit of the volatility of the stock market. Actually, you got double the volatility – 15% rolling 30-day volatility for the XLE versus half that – 7% – for the SPY.

Thanks for playing.

So what happened? By 2010, the Fed had gotten down to zero percent interest rates and was actively adding massive liquidity to the markets via several rounds of quantitative easing – buying bonds on the open market in exchange for dollars that it hoped would be put to work in the economy. And put to work it was. Money sought out projects with which to earn a return, and not all of them earned anything at all.

The shale energy boom has fundamentally changed the supply-demand dynamics for oil and gas around the world over the last ten years.

By the end of the decade, the coal industry is in complete liquidation, as dirt cheap natural gas from the shale boom upends an entire way of life in the Appalachian region, even as it has created massive amounts of jobs elsewhere, in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana.

By the end of the decade, Russia had become a global aggressor once again, partially in response to the pressure cheaper energy prices and more plentiful supply has put on its economy. This manifested itself in the form of election tampering / influencing across Europe and, a few years ago, right here in the United States – not to mention an ongoing hot war with Ukraine, which is a rival energy supplier to the Continent.

By the end of this decade, the US consumer had become not only the dominant economic growth engine at home, but also the preeminent source of economic growth on earth. The consumer now accounts for between 70 and 80% of the US economy.

And over in Saudi Arabia, the Kingdom is now desperate to modernize itself (economically), having brought Aramco – the state-run oil company – public (air quotes) at the end of this decade as it seeks to invite the world’s money into the country’s coffers. Saudi doesn’t just sell off a chunk of its energy dynasty for fun.

Investors in the energy sector have had a rough go of it because of all this new capacity in energy supplies. At first, it was a boom, but then it became a bust. Here’s a great explanation of how this all went down from James West at Evercore ISI (via Barron’s):

I think that there were a few things that conspired in 2010 to create what people term the oil-shale revolution. And that was low interest rates, high oil prices, wide-open debt markets and wide-open equity markets for energy companies to raise capital and chase oil shale. Since that time, energy companies spent well over $1 trillion in capex [capital expenditures], and have returned somewhere around $700 billion in cash flow to the [energy exploration-and-production companies]. Very little if almost zero of that went to shareholders, for a nice juicy negative 38% cash-on-cash return [cash flow divided by total cash invested]. So we clearly have an economic problem with the model. Now, three years ago, our team here at Evercore started to focus on some of the corporate-governance issues because we noticed this trend of negative returns and value destruction.

We’ve continued to focus on that, but as we’ve also peeled the onion back further and further on shale, what we’ve found is the technological advances, the efficiency gains that have come through have really not produced any kind of return profile that’s competitive with the S&P. And as a result, energy’s dropped from 15% or so of the S&P 500 to less than 5%. And if you take out Exxon and Chevron, you probably get to about 2%, if not less.

The plunging price of first natural gas and then crude oil has been the most disruptive force in the global economy over the last ten years, and the irony is that energy stock investors have nothing to show for it. The US consumer, having had more disposable income, has been freed up to spend more on data services, wifi, smartphones, vacationing, second homes, luxury pickups and SUVs, upscale fast food, yoga clothes, video games, celebrity cosmetics and $500 pairs of Yeezy’s and limited edition Air Jordans. Globally, energy producing nations have reacted with varying degrees of bellicosity (Russia), pragmatism (Saudi Arabia) and magnanimity (Norway).

I think, on balance, the endless supply of US shale energy throughout the 2010’s decade has changed the world order in a more profound way than anything else we’ve seen.

Leave a Reply