A gnawing fear of being caught up in the wrong place, a neighbourhood where protests have erupted or where police are pursuing aggressive curbs, prompted food delivery agent Afzal Afzi to wear his company T-shirt at all times.

“I wore it even when I was off duty. I hoped people or authorities would see that I am just a normal worker,” said the 23-year-old, who lives with his family in Warzipur, Delhi. “The T-shirt and the motorcycle painted in company colours gave me a sense of safety.”

But such small steps could not completely shield him and thousands of other gig workers from the emotional and financial toll linked to the widespread anger over the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, and to subsequent crackdowns by authorities.

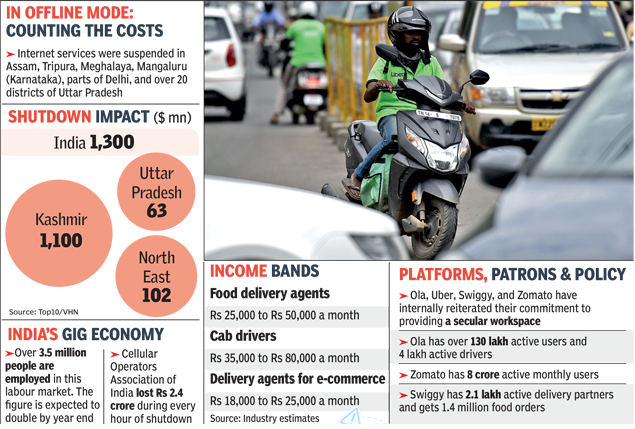

Internet shutdowns, curfew-like situations, and overall tensions about violence and police’s much criticised methods severely hurt demand and incomes in December, a usually festive period when online companies and gig workers expect brisk business. Internet blackouts cost India $1.3 billion in economic activity in 2019, according to a report.

“December turned out to be the worst period for us,” Afzal said. Videos and images of police clamping down on protesters left his family deeply worried about his safety. “Finally, my mother snatched my bike keys and didn’t return them for 10 days. When I rejoined work later, orders had still not picked up, and I struggled to cover household expenses and pay the EMI of Rs 6,500 for the bike.” Recently, his mother pledged her gold, so he can make the loan payment.

There have been similar stories of business disruption and hardship in Assam, Uttar Pradesh and other parts of the country. While internet blackouts generally affect industries, the effects are thought to be severe for sectors dominated by companies such as Ola, Uber, Flipkart, Amazon, Swiggy, and Zomato. And for the gig economy that supplies foot soldiers for drives and deliveries.

Food delivery agents earn between Rs 25,000 and Rs 50,000 a month, depending on the number of orders they complete, hours on the road, and distance covered, among other factors. Cab drivers can earn Rs 35,000 to Rs 80,000 a month, a chunk of which goes towards fuel, loans, and vehicle maintenance. A few years ago, when incentive packages were higher, they earned up to Rs 1.5 lakh for the same number of trips and hours.

Of all the stints at online businesses, delivering for ecommerce companies is the least rewarding: agents are paid Rs 18,000 to Rs 25,000 a month, according to industry sources. If one factors in rent, daily expenses and healthcare, gig workers in general are left with very little cash on hand or in their accounts.

India’s gig economy currently hires over 3.5 million people, a figure which is expected to double by year end. According to a study by the Indian Staffing Federation, India is the fifth-largest country in flexi-staffing after US, China, Brazil, and Japan. Analysts say for India to become a $5-trillion economy by 2025, it must grow at 10.8% CAGR (compound annual growth rate).

IT services and startups are expected to contribute significantly to the growth story. Since 2014, Indians startups have collectively raised $50 billion in 3,700 deals. In 2019 alone, tech startups raised $14.5 billion, up 37% from $10.6 in 2018, according to data intelligence platform Tracxn.

Uninterrupted access to internet is crucial to the success of this ecosystem. In Assam, internet services were suspended from December 11 to 19. “We were lucky that the high court intervened and ordered restoration of the services,” said Ismail Ali, who drives a cab in Guwahati, Assam. He heads the All Assam Cab Owners’ Association, which has 8,000 members.

“Even after internet was restored, it was not safe to take vehicles out as we feared protesters would smash our windscreens. We have monthly EMIs of Rs 10,000 to 15,000, and most of us have defaulted this month,” he said.

An estimated 12,000 cabbies work for both Ola and Uber in Guwahati, whereas about 8,000 agents deliver for Zomato and Swiggy. “We can’t afford to be associated with only one platform as we would not get that many orders. When internet was shut, everything came to a halt. I had to borrow money from relatives and a pawn broker to pay EMI of Rs 12,500,” said another cab driver in Guwahati, Jeet Thakur. He also pays rent of Rs 7,000. Thankfully, the landlord has allowed him to make partial payments towards dues of two months.

The trouble in Assam has a ripple effect on neighbouring states that rely on it for fuel supply. In Imphal, Manipur, long lines were reported at petrol stations. Food-delivery apps Zomato, Hummingbird and Foodwifi and e-commerce majors Flipkart and Amazon have operations in the city. “Many of us lined up from early morning. Even after waiting for hours, there was no fuel and we were asked to come back later,” said delivery agent Biswanath N. “Other people can perhaps leave and return, but delivery agents can’t go. If we do, we would lose our spot in the queue.”

He said the situation brought back memories from when he was a child and there were frequent bandhs. Any form of disruption means online businesses cannot complete orders in time. Imphal resident Premika Thockcham got her new sofa after 45 days. The seller apologised profusely, saying transportation had become a nightmare because of the protests and restrictions.

In Uttar Pradesh, where 19 people have died in CAA-related violence, 925 have been arrested and 5,000 detained, the tension is palpable. In Ghazipur, a manager at Flipkart-run Ekart, said delivery agents were reluctant to work because of safety fears.

“Attendance is low. They are reluctant to visit even areas which have not faced internet shutdowns. Right now, delivery boys don’t like the idea of venturing out,” he said. Underlining the challenges they face, he added: “Often, they have to travel to unknown neighbourhoods and find the right address. It can be difficult if the situation on the ground is tense.”

In Mangaluru, Karnataka, anti-CAA protests turned violence in December and police opened fire, which left two men dead. The incidents have shocked the coastal city, and the state government has ordered an inquiry into the violence and the firing.

“We have same-day alcohol delivery, food apps, a vibrant pub culture — all of it ground to a halt. It’s fear more than anything else,” said Manohar Shetty, who owns a restaurant in Mangaluru. “After the violence, it took some time for the business to pick up. Still, Christmas and New Year’s Eve were not the way they generally are. Definitely, not our best days this time; the crowd, in fact, was so thin that we wind up by 8pm.”

Leave a Reply