Executive Summary

With the recent market turmoil driven by the coronavirus pandemic, people around the world are understandably worried not only about the safety of their loved ones but also about the status of their life savings. In turn, financial advisors are working hard to help their clients think about (sometimes substantive) mid-course corrections to their plans but, at the same time, avoid panicked emotional reactions that could have even more detrimental effect down the road, and instead try to remain rational about their portfolio decisions. Yet the irony is that, in some circumstances, the process of becoming more emotional may actually play a crucial role in helping us address our irrational beliefs, and therefore the path to more rational decision-making may actually demand that we get more emotional first!

Research has found that emotions can play an important role in influencing decision-making by helping us form predictive models of the world that we are navigating. Our “emotional brains” can associate certain emotions with past memories and experiences that become encoded in our long-term memory (a process referred to as memory “consolidation”). Often this works well (e.g., don’t be mean to my friend, because then they won’t be my friend, and then I’ll be sad), but sometimes our emotional learnings can be triggered even when it is inappropriate for a given context, and this can lead to harmful rather than helpful behavior (e.g., don’t be assertive, because assertive people are rude, and people won’t like me if I’m rude).

In their book, Unlocking the Emotional Brain (UtEB), psychotherapists Bruce Ecker, Robin Ticic, and Laurel Hulley present a model of how emotional learning helps us navigate the world, and, importantly, how we can go about updating our emotional learning when it is leading us astray. According to the authors, we must engage in a process of memory “reconsolidation” in order to modify our emotional beliefs. The key to successful memory reconsolidation is to hold an emotional learning that is harming our decision-making in our consciousness—which involves getting into an emotionally activated state that really brings this emotional experience to the forefront of our mind—while holding some other experiential memory that contradicts the harmful emotional learning in our consciousness simultaneously. While our minds will generally be highly resistant to rationalizing away an emotional learning, the juxtaposition of two experiential memories in our consciousness simultaneously allows us to “unlock” a memory (i.e., deconsolidate a memory) and then change and “re-lock” that memory (i.e., reconsolidate) with some improved predictive model of the world (e.g., assertiveness isn’t always rude; perhaps we should be more assertive in the workplace than we are at a dinner party).

This idea has a lot of overlap with concepts such as Brad Klontz’s “money scripts” (i.e., beliefs about money which are so strong that we just act them out unconsciously). For instance, suppose John believes all rich people are evil (a money script) because some rich landlord wronged his family as a child. While there may be some logical basis for John’s belief in a very narrow context (e.g., perhaps his landlord truly did commit an evil act against his family), he’s currently overgeneralizing and that can be harmful. A key insight of UtEB is that we can’t just point this fact out to John and expect that the emotional learning will go away. Rather, we need to help him both unlock and modify this emotional learning by holding two contradictory experiential memories in his consciousness at the same time. The authors argue that, intentionally or not, many forms of therapy actually facilitate this type of juxtaposition which enables us to change our beliefs.

Similarly, in the current environment of turbulent markets, it may be important to acknowledge that we cannot simply rationalize clients away from their emotional beliefs. If a client is engaging in emotionally-driven investing, that investing may be rooted in some past emotional learning. Logic alone is not necessarily going to be enough to convince clients to stay the course. Rather, advisors may need to be able to help clients reconsolidate their emotional memories, which may require getting more emotional first before clients can update their predictive models of the world to incorporate the wisdom of not jumping ship. This insight may also be useful when we encounter passive non-compliance (e.g., a client who agrees to take action during a meeting, yet fails to ever do so), as passive non-compliance might stem from a client’s ongoing (but perhaps unspoken) struggle with and emotional belief.

Ultimately, the key point is that sometimes more emotion, not less, is first needed to help clients make better financial decisions. Advisors can assist in this process by engaging clients in conversations and exercises which may help both identify the root cause of some problematic behavior (e.g., an emotional learning underlying a money script) as well as lived experiences which contradict this emotional learning and therefore can be used to facilitate a process of updating our predictive models of the world to better align with reality. Advisors who learn to do this well can reap the rewards of truly helping their clients improve their financial decision-making!

How Emotions Guide Our Decision Making

It is no surprise to financial advisors that emotions often drive responses. Particularly in light of the recent market volatility and the fear (or greed) that can come with such environments, the role of emotion in influencing client behavior is something many advisors have been recently dealing with directly.

In a 2012 book, Unlocking the Emotional Brain (UtEB), Bruce Ecker, Robin Ticic, and Laurel Hulley present a neuroscientifically grounded account of the role that emotions play in forming memories and, ultimately, guiding our decision making. As their title alludes, emotions play a central role in the UtEB model. In a 2019 review, Kaj Sotala summarized the model as follows:

In a 2012 book, Unlocking the Emotional Brain (UtEB), Bruce Ecker, Robin Ticic, and Laurel Hulley present a neuroscientifically grounded account of the role that emotions play in forming memories and, ultimately, guiding our decision making. As their title alludes, emotions play a central role in the UtEB model. In a 2019 review, Kaj Sotala summarized the model as follows:

UtEB’s premise is that much if not most of our behavior is driven by emotional learning. Intense emotions generate unconscious predictive models of how the world functions and what caused those emotions to occur. The brain then uses those models to guide our future behavior. Emotional issues and seemingly irrational behaviors are generated from implicit world-models (schemas) which have been formed in response to various external challenges. Each schema contains memories relating to times when the challenge has been encountered and mental structures describing both the problem and a solution to it.

According to the authors, the key for updating such schemas involves a process of memory reconsolidation, originally identified in neuroscience. The emotional brain’s learnings are usually locked and not modifiable. However, once an emotional schema is activated, it is possible to simultaneously bring into awareness knowledge contradicting the active schema. When this happens, the information contained in the schema can be overwritten by the new knowledge.

While older models of emotional learning treated emotional learning as something that was fixed once a memory was “consolidated” (i.e., initially formed), more recent research has suggested that emotional learning may be malleable, and can be changed if the brain has been properly emotionally activated. This malleability is illustrated in memory reconsolidation, which plays a key role in the UtEB model, in which the process of activating an emotional memory is referred to as “deconsolidation”, and the process of changing an emotionally activated memory is referred to as “reconsolidation”.

Notably, the theory presented in UtEB has more basis than mere armchair theorizing, as important psychiatric and biochemical research, as well as research using molecular genetic techniques and neuroimaging, has been conducted in the field of memory consolidation. Although preliminary and not necessarily generalizable to humans, neuroscientific research using rats has also found that phobias among the rats can be removed via intervention, but only if the phobia had first been emotionally activated.

What the UtEB model suggests is that merely trying to rationalize away irrational thoughts or behavior would be futile. It is not enough to point out to someone that their views are inconsistent: If the desired result is changing a behavior, the emotional memory which is associated with the predictive model dictating the behavior to be changed must be activated so that the reconsolidation process can happen. And in order to reconsolidate an emotional memory, we must try to hold an irrational emotional memory and contradictory experiential evidence in our consciousness simultaneously.

So, for instance, it is not enough for us to tell a client that they need to start saving more for retirement. At some level, they likely already know that. If it feels like you keep spinning your wheels with a client who listens to your logical argument, seems to agree with it, and yet never implements your advice, there is likely an emotional barrier in the way somewhere.

While one part of a client’s brain understands the importance of saving, something, somewhere else in their brain (likely some emotional memory that is far more salient to the client), is interfering with implementing that behavior. To overcome that emotional memory will take more than mere rationalizing. The client will have to identify and hold that emotional memory in their consciousness while they confront it with contradictory experiential evidence.

This takes work—and it speaks to both why therapeutic approaches are often needed to change such beliefs and why those therapeutic approaches work.

In a 2019 blog post also discussing UtEB, Scott Alexander provides a “mental mountains” analogy which further helps elucidate the UtEB model:

UtEB’s brain is a mountainous landscape, with fertile valleys separated by towering peaks. Some memories (or pieces of your predictive model, or whatever) live in each valley. But they can’t talk to each other. The passes are narrow and treacherous. They go on believing their own thing, unconstrained by conclusions reached elsewhere.

Consciousness is a capital city on a wide plain. When it needs the information stored in a particular valley, it sends messengers over the passes. These messengers are good enough, but they carry letters, not weighty tomes. Their bandwidth is atrocious; often they can only convey what the valley-dwellers think, and not why. And if a valley gets something wrong, lapses into heresy, as often as not the messengers can’t bring the kind of information that might change their mind.

Links between the capital and the valleys may be tenuous, but valley-to-valley trade is almost non-existent. You can have two valleys full of people working on the same problem, for years, and they will basically never talk.

Sometimes, when it’s very important, the king can order a road built. The passes get cleared out, high-bandwidth communication to a particular valley becomes possible. If he does this to two valleys at once, then they may even be able to share notes directly, each passing through the capital to get to each other. But it isn’t the norm. You have to really be trying.

What the mental mountains analogy helps make clear is the ways in which we can compartmentalize contradictory information. To expand on Alexander’s analogy (though he alludes to this later in his post), mountains can vary in their height and other factors, which may influence how difficult it is for information to move freely between valleys. A mountain founded on emotional childhood trauma is likely to be much more difficult to pass than a more minor emotional belief that arose due to a lack of any other lived experiences to help formulate a predictive model of the world.

Alexander also draws connections to another seemingly complementary theoretical perspective put forward in Friston and Carhart-Harris (2019). Their paper is a bit more technical, but ultimately also comes down to how our brain holds predictive models of the world we operate in, and particularly in the context of the ways in which psychedelic drugs relax the beliefs embedded within our existing models of the world (they call their model the REBUS model, short for RElaxed Beliefs Under pSychedelics).

Interestingly, while the UtEB model focuses on consciously working towards forging paths through mountains, Friston and Carhart-Harris take an alternative approach to memory reconsolidation, noting that psychedelic drugs can be useful in psychotherapy because they are a means to reduce our strong priors that we often hold about the world. This can effectively accomplish the same goal, so long as the client can ultimately come to see the disconnect between their emotional beliefs and contradictory knowledge of the world they already possess. As Alexander puts it, “UtEB is trying to laboriously build roads through mountains; [Friston and Carhart-Harris] are trying to cast a magic spell that makes the mountains temporarily vanish.”

In either case, the essential goal of reconsolidation is to get different areas of our brain talking to one another in an emotionally activated manner that allows for updating otherwise contradictory beliefs.

While the goal of reconsolidation involves restructuring emotionally-based predictive models, it should be acknowledged that not all predictive models generated by emotional learning are bad. To some degree, we want to generalize and compartmentalize information in a manner that helps us navigate our environment. And oftentimes, these models are vital for making good decisions. If we didn’t generalize at all, then we would constantly be adrift and lost, struggling to take in an overwhelming amount of information without any ‘mental shortcuts’ to make even simple and seemingly mundane decisions.

For example, perhaps we once embarrassed ourselves with a social faux pas that violated norms among some corporate executives. The embarrassment we feel helps consolidate a memory that may help us be more acutely aware of not making a similar faux pas in the future. However that same behavior may be perfectly acceptable—even beneficial or appreciated—among friends on a golf course, and unfortunately our minds do not always limit the application of emotional learning to their specific context.

If we didn’t have mental mountains which help compartmentalize when a behavior is or is not appropriate, we would be forced to either overgeneralize and avoid a possibly beneficial behavior in the right context, or wander aimlessly and constantly relearn that a behavior is or is not broadly acceptable without putting it in its proper situational context.

How Financial Therapy (And Planning) Can Engage Our “Emotional Brains”

A 2015 review article published in Behavioral and Brain Sciences (Lane et al.) argued that different therapeutic approaches activate and modify memory structures in different ways. Sotala’s 2019 review also summarizes Lane et al.’s model well:

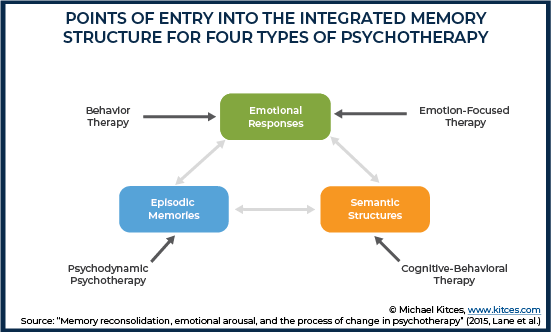

In their model, the schemas form memory structures with three mutually integrated components: emotional responses, episodic/autobiographical memories, and semantic structures (e.g. abstract beliefs which generalize over the various incidents, such as the claim that “people are untrustworthy”). Any of these components can be used as an entry point to the memory structure, and can potentially update the other components through reconsolidation. They hypothesize that different forms of therapy work by accessing different types of components: e.g., behavior therapy and emotion-focused therapy access emotional responses, conventional psychoanalysis uses access to biographical memories, and cognitive behavioral therapy accesses semantic structures.

If all of these models – the UtEB model (proposed by Ecker et al.), the REBUS model (proposed by Carhart-Harris and Friston), and the multi-therapeutic model (proposed by Lane et al.) – are pointing in the right direction, then they provide a basis for understanding why there is no one “best” form of therapy.

From the financial planning (and financial therapy) context, though, these models also help us understand that, in order for clients to make less “emotional” decisions, more emotion may be needed in the first place!

Notably, all of the therapeutic approaches in the graphic above have been proposed as useful within a financial therapy context being increasingly adopted by some financial advisors already. In thinking about the ways in which emotion influences financial behavior, Brad Klontz’s “money scripts” (and the various ways of dealing with them) seem to be of particular relevance.

Money scripts refer to unconscious beliefs we hold about money that influence our behavior. They are “scripts” because, like an actor or actress who knows their lines so well they can speak them without even thinking about it, they guide our behavior automatically. We don’t actively set out to employ money scripts, but, nonetheless, they influence our behavior. For instance, an individual may have the money script that “rich people are evil”, and, as a result, unwittingly engage in self-sabotaging behavior (e.g., a business owner subconsciously limiting the growth of their own business) because they never want to be, or at least been seen as, rich (and risk putting themselves in a position that they view as ‘evil’).

Interestingly, thinking of the mind as generating predictive models and formulating those models based on life experience is consistent with the notion put forward by Brad Klontz, Rick Kahler, and Ted Klontz in their textbook, Facilitating Financial Health, that many money scripts are formed early in life or from traumatic events.

According to UtEB, the outsized impact of early life experiences makes sense, since children have relatively few memories or experiences with which to evaluate the world and, therefore, are more prone to adopting a money script such as “rich people are evil”. And arguably, if children are going to successfully navigate the world, they need to formulate strong mental models quickly in their early years.

The key point, though, is that despite the fact that individuals will go about life with many contradictory experiences to their early-life money scripts, it doesn’t change those unconscious money scripts guiding their actions since emotional activation needs to occur before reconsolidation can happen. And individuals are unlikely to simultaneously hold money scripts and contradictory experiences in their consciousness simultaneously – necessary to break the hold – without some focused effort to do so.

Notably, similar emotional influences appear to be at play in the recently published “Sentimental Savings Study” in the Journal of Financial Planning. Led by Brad Klontz, this study was a double-blind random controlled trial comparing a traditional financial-educational seminar (e.g., covering topics such as time value of money, compound interest, etc.) to a financial psychology seminar which was designed to emotionally engage participants.

Results from the study indicated that individuals in the seminar which engaged them emotionally (e.g., participants brought a sentimental item with them that they engaged with to facilitate emotional activation, and once in that emotionally-activated state participants were asked to identify how similar feelings and values could be applied to their motivation to save) were more likely to report better outcomes following the study, such as a 73% increase in personal savings rates in the financial psychology group compared to only 22% in the financial education group.

From a financial education perspective, there may be at least two different processes at work with respect to consolidating emotional memories. First, in the event that individuals are learning something for the first time, it is possible the more activated emotional state was helping to facilitate consolidation (i.e., emotional learning for the first time). In the event that individuals may have come to the seminar with irrational financial beliefs related to savings, it is possible that emotional activation helped facilitate reconsolidation.

Notably, this interpretation is highly speculative, and the evidence from a single study in a financial context doesn’t really allow for any generalization, but it is some preliminary evidence that points in the direction of needing to engage our emotional minds before we can engage our rational minds to change our minds.

We can also look to some other models of financial therapy and find some consistency with the underlying process described in UtEB. For instance, solution-focused financial therapy commonly involves having clients first answer a “miracle question”, in which the client is asked to envision their life without some problem interfering. It is possible this type of reflection could fulfill the emotional activation needed by getting a client to (indirectly) think about a problem, albeit while maintaining a positive focus by thinking their life without that problem. Another common technique is to then ask clients to think about “exceptions” to their problem—i.e., circumstances in which the problem doesn’t seem to arise. In this context, exceptions will consist of experiential memories that do not align with the problematic emotional memories that may be underlying some behavior. Whether intentional or not, solution-focused brief therapeutic methods could be facilitating the process of simultaneously holding an emotional memory in consciousness along with a contradictory experiential memory, ultimately allowing for reconsolidation of the emotional learning and a corresponding update to a client’s predictive model of the world.

Practical Emotional Reconsolidation Strategies For Advisors To Use With Clients

So what does this all mean for financial advisors in practice? If the advisor has reason to believe that an irrational behavior, rooted in emotional learning, is keeping their client from following recommendations made as part of their financial plan, the advisor likely won’t be able to rely on purely logical arguments to change the clients’ beliefs. In fact, research implies that the best approach may be to not try to just talk clients away from their emotions and towards rationality, but instead specifically to engage a client’s emotions before rational discussion can occur (with the caveat of acknowledging that if advisors have reason to believe their clients may be experiencing more deeply seated psychological challenges, they should not attempt to engage in psychotherapy, unless they are qualified to do so, and should instead refer the client to a mental health professional.)

Identifying Clients’ Emotional Learning Blocks

According to the UtEB model, your clients may need to be emotionally activated before reconsolidation necessary for behavior change can happen, which means that it’s important to pay attention to possible emotional events that might underlie such beliefs. These events may not often be revealed from a normal financial conversation, but having clients go through exercises such as examining their money scripts may help bring some of these potential events.

Of course, this implies that one of the challenges for advisors is identifying whether beliefs are rooted in emotional learning. One important cue for identifying beliefs that may be rooted in emotional learning is resistance. As Klontz et al. note, “Resistance can take many forms, ranging from passive non-compliance . . . to more overt arguments against change.”

Some forms of resistance noted by Klontz et al. to look out for include arguing, interrupting, negating (e.g., “Yes, but…”), ignoring, and body language. In any case, resistance can be an important cue that emotional learning is interfering with client decision-making.

In practice, given the outsized role that traumatic events and events that occur early in childhood presumably have from the perspective of formulating predictive models of the world, advisors should be particularly mindful of money scripts grounded in trauma or early childhood experiences. (Of course, anything grounded in trauma warrants intervention from a properly trained therapist and goes beyond an advisor’s role, but merely identifying the need to potentially address some issues with a therapist could be a valuable observation, as well as being able to provide referrals to a mental health professional should there be a need to do so.)

As an example, suppose that, during a meeting with a client, an advisor presents a recommendation to purchase $1M in term life insurance, and the client agrees. Yet, by the time your next meeting comes around, the client hasn’t even started the application process.

Perhaps this process repeats itself a few times, with the client continually telling you, “Yes, I know, I need to get around to that,” but nothing ever happens. This would be an example of passive non-compliance. The client isn’t outright challenging the advisor, but they are passively doing so by repeatedly failing to take action.

Many advisors have had some experiences like this where they feel like they are just banging their heads against a wall. Passive non-compliance is arguably the most challenging (and frustrating) form of resistance to deal with, because at least with overt resistance (e.g., when the client specifically says, “I don’t think I need life insurance”) the advisor knows that their message isn’t resonating with the client.

With passive non-compliance, though, advisors think they are making progress and clients give you normal cues to affirm that the advisor is, indeed, making progress, but really aren’t. Advisors may think their logical argument (e.g., comparing the costs and benefits of term life insurance) is having an impact, because the client affirms that it is, but it’s really not, perhaps because there is some underlying emotional learning that is getting in the way.

How Advisors Can Use Emotional Reconsolidation Strategies With Clients

If advisors are going to try and assist clients in reconsolidation – recognizing that clients must be engaged emotionally – then they should be on the lookout for potential experiences/events occurring in the client’s life which contradict a client’s money scripts… as these lived experiences are crucial for the reconsolidation process.

Within the UtEB framework, a financial advisor may start the reconsolidation process by activating a client’s money script (i.e., bringing a client’s money script fully into consciousness by talking about the emotional experience underlying it). Different strategies could work here, but it is important that a emotional belief is given an opportunity to effectively “state its case” without an initial attempt to reject the belief.

Emotional activation is needed to bring the belief(s) underlying the money script to the forefront in all of its glory—after all, the script likely does have some underlying truth to it (e.g., perhaps an individual’s family was taken advantage of by a rich person), but it has simply been overgeneralized.

Example 1A. Suppose your client, John, is having a hard time following through with purchasing life insurance. In each meeting with John, you make a case for life insurance, and in each meeting, John tells you he realizes it is important and needs to get around to it, but it never gets done.

You realize you are encountering resistance, and you are curious about whether emotional learning might be getting in the way of this behavior. You have John complete an exercise you picked up from Klontz et al. to identify John’s money scripts, in which he completes a series of sentences (e.g., Wealthy people got that way by…, Only the rich can…) with the first thoughts that come to mind.

This exercise reveals an experience with a nasty landlord from John’s childhood. You probe a bit deeper using good interviewing techniques (active listening, pausing, etc.), and John reflects on how his family was kicked out of his childhood home after their landlord died, the landlord’s child inherited the property plus significant proceeds from a life insurance policy, and wanted to use those proceeds to renovate the property and turn it into a bed and breakfast (and evicting John’s family in order to do so).

Growing up, John’s parents could never afford life insurance, and he associated it as something that only rich people have. He overheard his parents often complaining about the life insurance proceeds their new landlord received (e.g., “If he didn’t have that life insurance money, he wouldn’t be kicking us out of our house to turn this place into a stupid bed and breakfast”).

Therefore, John internalized the message that not only is life insurance something for rich people (an identity he fights to avoid despite his own affluence because of his negative childhood perceptions of the rich), but specifically the type of rich jerks that would force his family out of their home to turn it into a bed and breakfast.

Based on this information, you engage John in another activity, where you ask him to bring that childhood memory of being kicked out of their home into his memory as vividly as possible. In order to “activate” this memory, you need to let John get back into it without any resistance.

You aren’t fighting it at this stage. You aren’t saying, “Aha, but see, not all rich people are jerks!”

You are just trying to get the memory in John’s consciousness as vividly as possible.

Your next challenge, as an advisor, is to guide your client to also bringing a contradictory experiential memory into view at the same time. Note that the experiential element is important here, as this isn’t merely an attempt to rationalize since rationalizing will not have the emotional salience needed to elicit the desired effect.

The individual needs to hold the money script (e.g., rich people are evil) in consciousness at the same time as some emotional experience (e.g., Susan is rich, she’s not evil, and the time she helped pay off our medical bills brought relief to my whole family). This tension between two emotionally activated predictive models can potentially allow for the reconsolidation process to eliminate (or modify) a harmful money script.

Example 1B. Unrelated to the money script exploration you have been doing with John, you also recall that he had a good friend, Mike, who nearly passed away after being in a traumatic accident.

The doctors initially did not expect Mike to live, but fortunately, he was able to pull through. The experience really shook John, and as you were discussing the situation before the outcome was known, he said, “I don’t know how they are going to make things work financially, but Mike’s wife, Sarah, says that they have life insurance and they’ll be fine.”

You identify this past memory as a potential piece of counterevidence that you can use to help Mike overcome his existing emotional memory.

With the memory of John’s evil, rich, life-insurance-benefiting-landlord in consciousness, you then ask John to recall Mike’s ordeal and the financial situation his family was in before his fate was known.

As a reminder, you also redirect his thoughts back to his belief that only evil, rich people own life insurance. And then you ask John to re-live the conversation he had with Mike’s wife about their financial situation.

The dialogue played out as follows:

John: Mike was in the hospital. He was in a coma. It didn’t look good. We didn’t think he would survive.

I really didn’t know how they would make it work financially; Sarah had been staying at home with their kids and didn’t have an income. I didn’t want to say anything, but without asking, she told me he had life insurance, so they would be fine.

I guess that’s interesting to reflect on now. Mike’s not evil, but he had life insurance. The life insurance might have actually done a lot of good for his family.

You: Keep going with that thought – on the one hand, your old landlord had life insurance proceeds and used those funds to do something that was painful to your family. On the other hand, Mike had life insurance, and he is not evil.

So, how does it feel to reflect on both of these things that you know to be true?

John: It’s an odd feeling, I guess. I’ve never really thought of it this way.

Ultimately, the key here is for you just to guide John towards holding both of these beliefs in his consciousness simultaneoulsy; now is not the time to argue, for instance, about whether or not the landlord had a right to use the property as he saw fit.

In the present context of high market volatility, there may be many opportunities to assist clients struggling with emotional decision-making as well.

Example 2. Suppose you have a 35-year old client, Chris, who calls you continually fearful about the the latest 5% drop in the S&P 500. On multiple occasions, you have led Chris through the usual logical discussion of why it makes sense to stay the course (e.g., he has a very long time horizon, even if he times the market down it’s hard to time the market up, etc.). Logically, Chris always seems to come away from the conversation understand, yet your phone keeps ringing. Intentionally or not, Chris is engaging in a form of passive non-compliance. He knows what you are going to say, he’s had the logical conversation time and time again, but yet he still calls.

This passive non-compliance is likely a sign that there’s some underlying emotional learning that is influencing his behavior. So, no matter how much logic you throw at him, it simply is not going to work. You decide to engage Chris in some exercises to uncover his money scripts and general beliefs about finances. Through this discussion, it is revealed that Chris’ father, who took very little risk in his own investments (at least risk he was aware of) and relied fully on his pension for retirement, used to talk about all the greedy idiots who lost money being invested in the stock market. Chris internalized the message, “If I lose money investing in the stock market, I will become the type of greedy idiot my Dad dislikes.”

Having identified the belief you think could be underlying Chris’ reluctance to stay in the market, you recall that his boss, Jeff, is someone he looks up to and has encouraged him to save diligently for his retirement, just as he did himself. At this point, you have Chris recall his Dad’s views about people who invest in the market. While maintaining that thought in his mind, you also have Chris begin to reflect on his relationship with Jeff. You ask questions which bring into focus the fact Jeff is not a greedy idiot despite his own investing in the market—with corresponding paper losses that always occur—and Chris will hopefully be able to update his emotional beliefs to acknowledge that just being invested in the market does not make him a greedy idiot.

Now, in practice, conversations won’t necessarily play out as smoothly as examples above. The examples are simply an attempt to illustrate the process of getting a client to hold onto an emotional belief in their consciousness while simultaneously reflecting on contradictory information (based on a lived experience and not just an advisor’s logical argument) that they also know to be true.

In UtEB, the authors provide additional detailed dialogues with more conversational strategies that could help facilitate this practice (e.g., lots of repetition, specific phrasing of repeated questions, verification processes to see if a memory has been reconsolidated, follow-up tasks intended to affirm the learning, etc.). Financial therapy books – such as Facilitating Financial Health by Rick Kahler and Ted Klontz, Financial Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice by Brad Klontz, Sonya Britt, and Kristy Archuleta, and Communication Essentials for Financial Planners by John Grable and Joseph Goetz – also have many communication tips that can be helpful for facilitating a reflective conversation, such as the example above.

Of course, advisors will always need to be careful to maintain appropriate boundaries, but the key point is that the desire to get clients to engage more “rationally” may actually need to start by engaging emotionally.

In other words, in order to help clients to stop making irrational decisions driven by emotion, advisors (or therapists) may, ironically, need to get clients more engaged emotionally first!

Leave a Reply