The 2020 presidential campaign could mark a turning point in resolving Social Security’s long term financial stability.

It comes down to simple math: Some 73 million baby boomers will be at least 65 years old by the end of the decade. The coronavirus pandemic could deplete the program’s $3-trillion trust fund as early as 2028, seven years ahead of the current insolvency date. Neither of the major-party candidates are proposing any cuts to the program, which remains broadly popular.

“The next president is going to be faced with dealing with that,” says Mary Johnson, a Social Security and Medicare policy analyst with a nonpartisan advocacy group called The Senior Citizens League. “We need to be talking about the plans, what the parties’ plans are and what they propose going forward.”

Beyond pledging to protect Social Security, President Trump hasn’t released comprehensive proposals like the ones found on former Vice President Joe Biden’s campaign website. Biden’s plans follow a primary fight in which he had to repeatedly address criticism that he’d tried to cut benefits for 40 years.

Representatives for the president’s reelection campaign referred Financial Planning’s request for Trump’s ideas for Social Security reforms to the White House, which didn’t respond to requests for comment. Representatives for Biden’s campaign didn’t respond to inquiries, either.

Interest groups that have studied the issue over decades were not eager to discuss the prospects for Social Security reform after the 2020 election: The Bipartisan Policy Center, the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation didn’t respond to emails. Representatives for AARP said no one was available for an interview.

“We don’t want to get in the business of critiquing candidates’ proposals,” AARP spokesman Colby Nelson said in an email. He added that AARP focuses on ensuring that candidates are clear to voters about their stances.

Both parties are acknowledging the stakes and the increasing urgency due to the impact of the coronavirus on payroll tax revenues and other factors. The program is poised for “a real reckoning,” Rep. John Larson (D-Conn.), the chairman of the House Ways and Means Social Security Subcommittee, told Politico in May.

In an interview with the same publication, Rep. Steve Womack (R-Ark.), the ranking Republican on the House Budget Committee, referred to Social Security’s finances as “a train wreck that’s going to happen and you can see it coming.”

The modest proposals

President Trump has never hewed closely to plans calling for long term changes to entitlements, like proposals by former House Speaker Paul Ryan. Last month, the Trump administration reportedly weighed an idea floated by conservative scholars to pre-pay Social Security benefits to workers hard hit by the pandemic. Trump’s team has rejected the proposal, though.

“President Trump has been clear that while he is in office, the American people can feel secure without a shadow of a doubt that he will completely protect Social Security and Medicare — end of story, full stop,” the administration told The Washington Post, which first reported that the White House considered the idea.

Biden has called for raising the benefits of the oldest Americans in danger of outliving their savings and boosting minimum payments to retirees who spent 30 years in the workforce to 125% of the federal poverty level. Critics charge that such plans would push benefits beyond what the government already cannot pay in full after 2035.

At the same time, Biden’s plan would apply the payroll taxes, which finance the program, to wages above $400,000. The current 12.4% tax on workers and employers only touches the first $137,700.

“The Biden plan will put the program on a path to long-term solvency by asking Americans with especially high wages to pay the same taxes on those earnings that middle-class families pay,” according to the former vice president’s campaign website.

A way forward?

While increasing taxes rarely garners much support in Washington from either party, it may be gaining steam. The Senior Citizens League found widespread support among its members. The advocacy group has grown to an independent organization of 1.2 million people since it started as an offshoot to a professional organization for enlisted military personnel and their families.

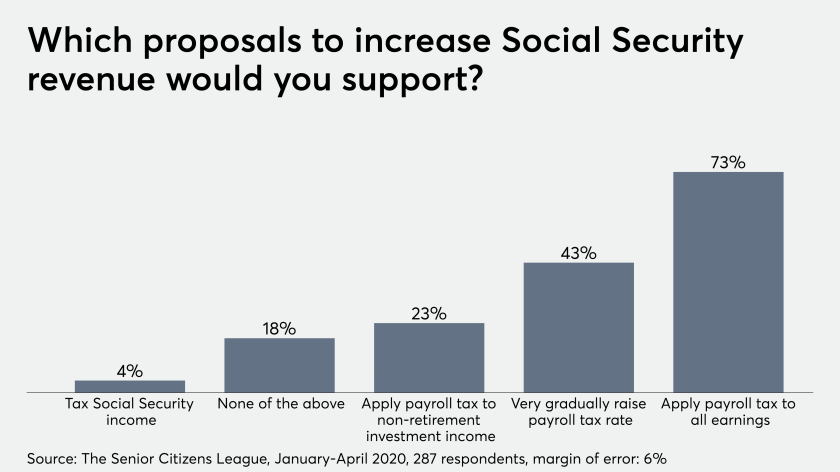

In a small sample of 287 older adults who chose to participate in an email survey released in January, 209 said they would support expanding the taxes to all payroll earnings in order to raise revenue for the program. The results look similar to other polls by the group in recent years that surveyed older adults from both parties and across all political ideologies, Johnson says.

“They favor approaches that do not cut benefits to resolve the financial imbalance,” she says. “They would much prefer to see people pay a little bit more while they’re working than to cut benefits later.”

The White House and Congress could find themselves in the awkward position of presiding over benefit payments cuts of up to 25% when the trust fund runs out, Johnson adds.

“Doing nothing is not an option because, by law, the revenues would adjust and that would be like an automatic cut,” she says. “We don’t want that to happen and I don’t think Congress would allow that.”

Leave a Reply