Executive Summary

Industry media has often noted that gender pay gaps among financial advisors are shockingly large – with gaps observed as high as 40% or more. However, these headline-grabbing numbers don’t tell the full story. In particular, just looking at ‘raw’ pay gaps (i.e., gaps that don’t adjust for other relevant pay-related differences between men and women) can be misleading, because it doesn’t tell us whether the gap results from men and women being paid unequally for doing equal work, from men and women being paid relatively equally but working in different capacities, or from some combination of these factors. In fact, the Bureau of Labor Statistics—the entity that publishes the data most advisor gender pay gap statistics are based on—explicitly cautions that their data does not include the relevant information needed to fully assess a pay gap.

At the same time, many misunderstandings exist with respect to how to interpret and understand pay gap analyses themselves. For instance, just because a gap does not remain after controlling for relevant differences does not suggest that gender discrimination is not an issue within an industry. A proper pay gap analysis will control for relevant differences in worker characteristics (e.g., job role, hours worked, productivity, etc.), but if differences in these characteristics are themselves the result of discrimination (e.g., a ‘glass ceiling’ effect in which equally qualified women are passed up for promotions for discriminatory reasons), then this effect will not be picked up in a pay gap analysis. Such effects are not picked up because a gender pay gap analysis is only examining the very narrow question of whether men and women receive equal pay for equal work, and not the broader question of whether other discriminatory factors may influence the roles that individuals end up in. On the other hand, another common way to misinterpret a pay gap analysis is to conclude that any unexplained gap is evidence of discrimination. Discrimination is one possible explanation, but there are alternative explanations, such as researchers not having access to other relevant variables that should have been controlled for.

In the context of the financial advisory industry—an industry that has long been male-dominated and has struggled to recruit more women into the field—understanding the extent to which we do see evidence of potential discrimination is important, as the common message that women are not paid equally in our field could itself be a factor discouraging women from pursuing a career in financial planning. Accordingly, using data from our 2018 Kitces Research Study, we conducted what was, to our knowledge, the first gender pay gap analysis among financial advisors that examined more than just the ‘raw’ gap between men and women.

Based on highly detailed information provided by over 700 financial advisors, we observed a ‘raw’ gender pay gap of 19% among financial advisors before controlling for a number of factors such as experience, credentials, advisory role, team structure, hours worked, revenue produced, marital status, and psychological motivators around compensation. The gap we observed is likely lower than the ~40% commonly reported in the media because we excluded administrative workers, many of whom would be included in the BLS statistics. However, the factors controlled for in our study (including both revenue and time spent, and the preference for variable vs stable salary income) explained 91% of the gender pay gap observed, leaving an unexplained gap of just 1.8 percentage points. Discrimination is one potential factor that could explain this remaining gap of 1.8 percentage points, although other factors, such as relevant variables that were not included in our study, could also explain the remaining gap. Notably, the biggest driver of the pay gap that we observed was the tendency for men, on average, to be more motivated by income potential (and ostensibly choosing more variable-compensation revenue-sharing roles), while women were, on average, more motivated by stable pay (and thus may tend to choose salaried roles with less long-term upside).

Of course, as noted previously, our findings do not suggest that gender discrimination is not an issue within financial planning. In fact, previous research has found that factors such as ‘performance support bias’ (e.g., the assignment of better accounts to men relative to women when a broker leaves a firm) do contribute to the advisor gender pay gap in a manner that would be missed by our study. Furthermore, a follow-up Kitces Research Study in 2019 that sought to examine relationships between family characteristics and advisor earnings (since the “motherhood penalty”—i.e., systematic biases that working mothers face in the labor market—contributes significantly to the gender pay gap in many fields) and did find gender differences in relationships between income and family-related characteristics among advisors. For example, we found evidence of a ‘marriage premium’ and a ‘stay-at-home spouse premium’ among men but not women, providing support to the notion that factors outside of the workplace may also be influencing earnings differences amongst advisors, and emphasizing that work to further close the gender pay gap should be cognizant of addressing these complicated factors.

At the same time, we do believe there are potential reasons to be optimistic about our findings. While we could not examine all potential types of gender bias, at least on this narrow form of potential discrimination (unequal pay for equal work), we did not find evidence of significant gender discrimination. We see this as a positive message for women who otherwise fear that they may not be paid fairly if they pursue a career as a financial advisor. Furthermore, women were represented among all levels of advisor success, including the highest earners bringing in over $1 million in annual personal income. And while it did appear that, on average, women prioritized some career choices over income to a greater extent than men, average income among women was still very high relative to income levels of most Americans ($165,000 for women in 2018 and $197,000 in 2019). So, to the extent that advisors (regardless of gender) may select different pathways within the industry based on personal preferences (e.g., selecting a stable-pay job because of a desire/choice to use that as a foundation to start a family and have more work-life flexibility), it still appears that excellent career opportunities are available regardless of preferences.

Ultimately, the bottom line is that despite widespread reports of large gender pay gaps within the financial advisory industry, we did not find evidence of unequal pay for equal work. And while our studies do identify some differences in income between men and women in the advisory industry, other relevant differences, particularly with respect to work and income preferences, explained most of the gender differences in income that were observed. While our findings should not be interpreted as suggesting that gender discrimination is not an issue within the industry (as there are many forms of potential discrimination that would not show up in a pay gap analysis and other limitations to consider), our findings do suggest that perhaps, at least on the narrow dimension of unequal pay for equal work, the news is not as bad as commonly reported.

The financial industry media often runs stories emphasizing that the financial advisory industry has one of the largest gender pay gaps of all industries. In recent years, websites such as MarketWatch, Fortune, Financial Planning, and ThinkAdvisor have all run stories covering the large gender pay gap for financial advisors. The gender pay observed among financial advisors based on earnings data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has often historically measured around 40% (e.g., 41% in 2017).

However, publicizing the ‘raw’ (i.e., unadjusted) gender pay gap controlling for other relevant differences goes directly against guidance from BLS itself, which cautions that the classifications used in the BLS study “are not sufficiently precise with respect to specific job skills, responsibilities, and specialization” and that income figures “are not simultaneously controlled for differences in important determinants of earnings such as age, educational attainment, and work experience”.

Thus, the gender gaps commonly reported in financial media don’t actually provide insight into whether men and women in the advisory industry are paid unequally for equal work. And this is concerning for several reasons. First, we can’t know the true extent of a problem and how to best address it if we don’t properly measure it. Proper measurement could indicate that the gender pay gap is larger, smaller, or roughly equivalent to figures commonly reported. Second, from the perspective of working towards the goal of building a more inclusive and diverse industry, the current practice of perpetuating a narrative that women are paid unfairly (without true evidence to support that claim) could unintentionally discourage women from entering an industry that has already struggled to achieve greater gender diversity.

A Note About Gender Pay Gap Research

Before we delve into our research on the gender pay gap among financial advisors specifically, it is important to address some common misconceptions regarding what gender pay gap studies are actually examining. So, before we dig deeper into what we’ve found in our Kitces Research studies have found regarding gender pay gaps, it is helpful to clarify what gender pay gap studies are (and are not) actually examining.

Nerd Note: It is common in research to distinguish between sex and gender. Generally speaking, sex is used as a biological classification whereas gender refers to sociocultural roles. Because our past research has asked participants how they identify, we are interested in the self-identified sociocultural classifications rather than biological classifications. Throughout this post, we use the terms man/male and woman/female interchangeably to refer to one’s gender identification.

Misconception #1: A Lack Of A Pay Gap Suggests That Discrimination Is Not An Issue

First and foremost, it is important to understand that a gender pay gap analysis examines whether men and women receive “equal pay for equal work”. In a pay gap analysis, “equal pay for equal work” refers to whether men and women in equal positions, with equal responsibilities, equal experience, equal credentials, etc. earn the same amount. Notably, this is confining the analysis to a more narrow conception of discrimination than many people realize. In the workplace, “equal pay for equal work” is only one of many potential forms of gender discrimination. An industry could actually pay men and women equally for equal work and yet still be rife with discrimination that leads to unequal outcomes (including, confusingly enough, unequal outcomes in pay!).

For instance, the “glass ceiling” effect is commonly used to describe situations in which equally qualified women (relative to men) are passed up for promotions or other career advancements, and this is an example of an effect that would not be picked up by a traditional pay gap analysis. This happens because proper pay gap analyses are going to control for relevant factors which we would expect would influence earnings (e.g., job role, experience, hours worked, etc.), but if discrimination leads to disproportionate outcomes with respect to these relevant factors themselves, then a pay gap analysis that controls for such factors may indicate that men and women are paid equally for equal work while still missing a very important form of discrimination that is leading to unequal outcomes.

To give a more specific example, a study may find that men and women are paid equally for equal work (e.g., female managers are paid the same as male managers; female executives are paid the same as male executives; etc.). However, discrimination could still be problematic if equally qualified men and women were selected for promotion into executive positions at disproportionate rates. Therefore, “equal pay for equal work” does not suggest that there aren’t other discriminatory problems such as “unequal promotion for equal work”. That type of discrimination cannot be picked up by a traditional pay gap analysis, because questions regarding fairness in promotion would need to be analyzed using different methods.

In the context of financial advisors, this is important as it means that, for instance, if discriminatory factors held a highly qualified woman back from reaching a lead financial advisor position and kept her in an associate advisor role, a pay gap analysis examining salary based on job position might not reveal any inequality when examining her salary relative to other associate advisors. However, in terms of equal gender opportunities, a pay gap analysis, in this case, could entirely miss the point. A pay gap analysis will not pick up the gap that would emerge between her and the equally or less qualified male advisor that did receive a promotion for discriminatory reasons.

And the glass ceiling effect is only one possible discriminatory effect that could influence outcomes in the manner described above. Within a financial advisory context specifically, a 2012 study from Janice Madden at the University of Pennsylvania found that when a stockbroker left a firm and the departing broker’s accounts were being reassigned, managers were giving higher-quality accounts disproportionately to male advisors over female advisors, despite the fact that male and female advisors were equally productive when each group was given equal opportunities (an effect Madden refers to as “performance-support bias”).

And this is precisely the type of discriminatory activity that can be missed by a gender pay gap analysis (which might find that the male and female advisors at that branch were being compensated consistently based on the number of clients they were servicing… without recognizing the discriminatory policies that led men to have more opportunities for clients than women in the first place), so it is important to keep in mind the very narrow nature of the question that a gender pay gap analysis is actually exploring.

Misconception #2: An Observed Pay Gap Can Only Be Explained By Discrimination

At the same time, it is also important to acknowledge that there are many misperceptions regarding the size and prevalence of gender pay gaps in the workforce. These misperceptions are commonly driven by reports from the media and elsewhere that look at gender pay gaps without controlling for relevant differences, similar to reports that are common within the financial industry media.

As was mentioned earlier, commonly touted statistics regarding the gender pay gap among financial advisors often do not control for relevant factors such as job role, experience, and productivity. If we want to examine the question of whether men and women in the financial advisory industry receive equal pay for equal work, then it is important to control for all of these factors. As was described above, we may miss other forms of discriminatory behavior, but those questions are outside of the scope of a pay gap analysis.

To our knowledge, there are no previous pay gap analyses that properly examine the pay gap among financial advisors after controlling for relevant factors. However, we can look at meta-analyses (i.e., analyses that combine results from several studies examining gender pay gaps) to provide some broad generalizations about labor market research related to the gender pay gap. In particular, meta-analyses from 1999 and 2004 in the Journal of Human Resources and 2005 in the Journal of Economic Surveys have examined the pay gap in great depth. Looking at these studies, we generally see that in other fields, often about 90% of raw gender pay gaps can be explained by controlling for relevant factors such as education, experience, and job role. Furthermore, high-quality studies (e.g., studies which can control for a greater number of factors) tend to find smaller gaps.

So, to put that in context, if a gender gap of 20 percentage points is observed, typically 90% (or 18 percentage points) of that gap can be explained by differences in education levels, work experience, job role, and other relevant factors assessed, while a 10% of the initial gap (or a 2-percentage-point gap) could not be “explained” by the factors considered.

Another misconception, however, is to assume that any of this remaining gap (e.g., the 2-percentage-point gap in the example above) is necessarily due to discrimination. Discrimination (i.e., unequal pay for equal work) is one potential explanation, but the remaining gap could also be attributable to many other factors, including other relevant differences between men and women that are not captured within a researcher’s dataset (commonly referred to as omitted variable bias).

Unfortunately, the reality is that there is often a large number of important unobserved differences between workers that researchers simply do not have access to. Some recent studies of particularly high-quality have illustrated this point well.

One team of researchers recently examined the gender pay gap among bus and train operators within a unionized environment. What was interesting about this study of bus and train operators was that, despite being in a unionized environment that makes it incredibly difficult for managers to engage in any sort of gender discrimination, a pay gap between men and women in this environment was still observed. Furthermore, an 11-percentage-point gender pay gap remained even after accounting for factors that are commonly available in a pay gap analysis. In many past studies, researchers wouldn’t have been able to go any further. However, because these authors also had access to information on worker characteristics not commonly available in pay gap analyses (e.g., such as work-related choices and preferences made by workers within the study), the authors were able to observe that these choices and preferences were what explained the remainder of the pay gap. Specifically, women in this study took fewer overtime hours and opted for more unpaid time off per week, which resulted in a pay gap even within a unionized environment.

Another recent study examined the gender pay gap among Uber drivers. Similar to a unionized environment, a pay gap among Uber drivers is interesting because researchers can verify that all work is assigned via an algorithm that entirely ignores gender. Nonetheless, a 7-percentage-point gender pay gap was still observed. Similar to the bus and train operator study, in many prior pay gap analyses researchers would have to stop the analysis here by noting a 7-percentage-point pay gap (possibly explained by discrimination or possibly explained by something else). However, because the researchers had access to additional data not typically available, they were able to determine that the observed gap was ultimately explained by differences such as working environment (e.g., the men assessed in the study tended to live closer to more lucrative locations and showed a willingness to drive in higher-crime areas and in locations with more drinking establishments) and the tendency for men to take greater risk by driving faster (and thus covering more distance, which directly results to higher pay).

In summary, prior meta-analyses indicate that about 90% of the ‘raw’ gender pay gap can be explained by factors typically available within pay gap studies (which is a much smaller gap than commonly touted ‘raw’ gender pay gaps). With respect to the 10% portion of the gender pay gap that typically still remains, this could be attributable to discrimination, but it could also be attributable to a lack of relevant data, as has been illustrated in some recent analyses. However, as noted previously (see Misconception #1), a lack of a gender pay gap is not evidence of a lack of gender issues within an industry.

Kitces Research Studies on the Financial Advisor Gender Pay Gap

Thanks to the 1,000+ financial advisors who took the time to provide detailed information about their practices via our Kitces Research Studies, we have been able to conduct some of the first gender pay gap analyses amongst financial advisors that can actually control for other relevant differences.

Gender Pay Gap For Financial Advisors Is Not Statistically Significant Once Adjusted For Relevant Controls

In an article recently published in Financial Planning Review (the CFP Board’s new financial planning research journal), my coauthors (Meghaan Lurtz, Katherine Mielitz, Michael Kitces, and Allen Ammerman) and I analyzed the gender pay gap among a sample of 710 financial planners (584 male; 126 female) from our 2018 Kitces Research Study. Given the highly detailed information we had about respondents, we were able to control for several key factors including experience, credentials, an advisor’s role (i.e., lead advisor vs. support advisor, etc.), team structure (i.e., solo firm vs. ensemble firm, etc.), hours worked, revenue produced, marital status, and psychological motivators related to compensation (e.g., motivation by income potential, performance pay, work-life balance, and stable pay).

Overall, we found a 19-percentage-point raw gender pay gap in favor of men before controlling for other factors (average incomes among men and women, respectively, of roughly $200,000 and $165,000). This gap was likely lower than the ~40% gap observed in the BLS data since one limitation with the BLS data is that many administrative workers who are often licensed as financial advisors but who may not truly work as financial advisors (e.g., registered assistants) could be captured in this classification (and, historically, these employees have been disproportionately female).

By contrast, financial advisors who take our surveys tend to disproportionately be financial advisors, who actually do work as financial advisors; therefore, it is not surprising that our unadjusted pay gap was smaller than the unadjusted pay gap found by the BLS. Furthermore, we excluded the small number of respondents who indicated that they did work in an administrative role.

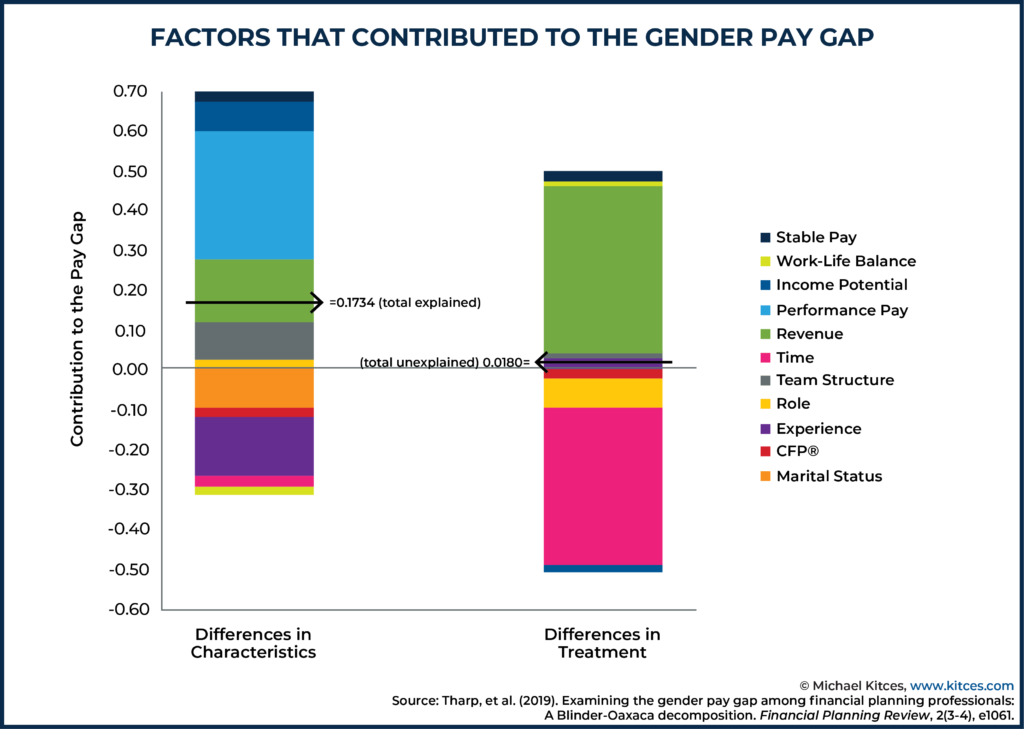

Using Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis (a method most commonly used in pay gap studies), we found that 91% of the 19-percentage-point unadjusted pay gap (i.e., 17.2 percentage points) could be explained by the factors included within our model, leaving an unexplained gender pay gap of just 1.8 percentage points (which was no longer a statistically significant gap).

Nerd Note: We also examined a number of other model specifications and robustness tests, which indicated that anywhere from 74% to 148% of the pay gap was explained. Estimates of greater than 100% would indicate a pay gap that may actually favor women after accounting for factors within our model, however, all of the previously mentioned caveats would still apply.

When looking at individual factors that contributed to (but then also helped to explain) the pay gap, the largest factors, in order, were motivation by performance pay, revenue production, team structure, and motivation by income potential.

In the graphic below, the key area to focus on in understanding what “explained” the pay gap in our analysis is the relative size of the different factors above zero in the “differences in characteristics” column (larger factors explained more). As the chart indicates, motivations regarding preferences for performance pay contributed the most towards the pay gap, followed by revenue production and team structure.

Not surprisingly, advisors who were more strongly motivated by performance pay and income potential tended to earn more than advisors who were less motivated by these factors. This factor alone explained the largest portion of the pay gap. Similarly, advisors who produce more revenue were paid more, and advisors who utilize team structures that provide operational leverage (e.g., a solo advisor with support staff or ensemble teams) earned more than advisors who do not (e.g., a solo advisor without support staff or silo teams). Which means, in essence, that male financial advisors may not receive significantly more pay than female financial advisors on an all-else-equal basis, but they are more likely to have some combination of the above factors (more motivated by performance pay and income potential, producing more revenue, and/or more likely to have a team supporting team), which then results in higher average incomes for men.

Family Characteristics Impact Income Of Men And Women (Financial Advisors) Differently

In follow-up work using our 2019 Kitces Research Study (which currently has not yet undergone peer review), my coauthors (Elizabeth Parks-Stamm, Meghaan Lurtz, and Michael Kitces) and I explore gender differences in marital and parental income premiums for financial advisors.

While we do find a similar unadjusted pay gap of 17-percentage-points (average income amongst men and women lead advisors of roughly $236,000 and $197,000, respectively), in this study, only 51% of the gap was explained by the variables included in the model. However, in this follow-up study we were not able to include the psychological variables related to income motivation (which were not collected in this iteration of the Kitces Research Study) that were found to be most important in our first study.

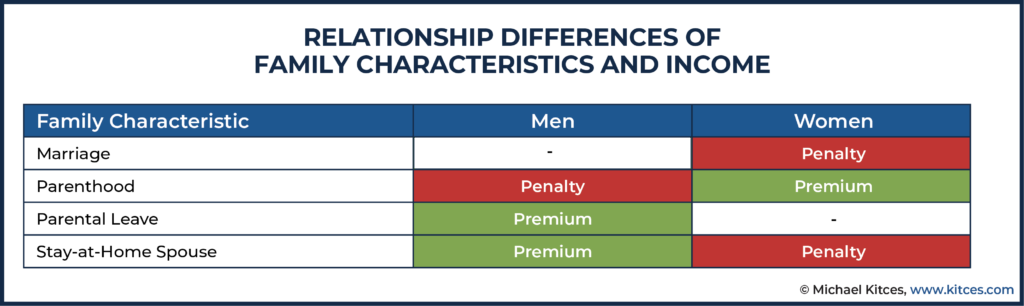

The primary interest of our follow-up study was not the gender pay gap, per se. Instead, we were looking at how family characteristics (e.g., marriage, children, etc.) may differently influence earnings among male and female advisors, and we did observe important differences in the relationships between family characteristics and income.

For instance, we found that a marriage penalty was observed among women but not men (i.e., marriage was negatively associated with income among women but not men), a parenthood premium was observed among women while a parenthood penalty was observed among men (i.e., parenthood was negatively associated with income among women but positively associated with income among men), a parental leave premium was observed among men but not women (i.e., having taken parental leave was positively associated with income among men but not among women), and a stay-at-home spouse premium was observed among men while a stay-at-home spouse penalty was observed among women (i.e., having a stay-at-home spouse was positively associated with income among men but negatively associated with income among women).

There is some nuance to our findings regarding exactly how we specify our models and what control variables we include, but the high-level takeaway is that family characteristics seem to be related to income differently among men and women. This is notable given that past research has found that the division of household labor and other considerations can influence career opportunities.

It is fairly common in the family economics literature to find relationships such as a marriage income premium among men and a marriage income penalty among women. After the birth of a first child, fathers tend to work more and take on more labor market responsibilities, while mothers tend to take on more household labor responsibilities. There’s disagreement as to why these differences emerge–and clearly, men not taking on an equal share of household responsibilities is one potential explanation, although there’s also some evidence that, at least among some couples, men and women both prefer taking on increased responsibility within each domain–but these relationships are commonly observed nonetheless.

It is also fairly common in the family economics literature to observe that men tend to disproportionately benefit from having a stay-at-home spouse. Again there is disagreement as to why this is, but this general finding is consistent with our study.

Within a financial advisory context specifically, this may be particularly relevant given that fields such as finance, business, and law tend to have non-linear earnings such that one spouse working 60 hours per week might be able to earn more than both spouses working 40 hours per week in the same field. This tends to be true in fields like financial planning, where employees are not easily substitutable, but it is less true in fields like pharmacy and health sciences where employees are highly substitutable.

Our findings related to different outcomes associated with having taken parental leave are also interesting, although we express some skepticism of these findings given how long ago many advisors in our sample took leave (e.g., an advisor in their fifties may have taken leave 20 or 30 years prior) and the likelihood that other factors may be driving this.

Nonetheless, we again observe many similar relationships as found in our first pay gap study, such as higher earnings among advisors bringing in more revenue and working in environments that allow them to better leverage their time.

One additional interesting finding within this study was that education was generally not a predictor of income among advisors. Furthermore, within some models used in our study, lower levels of education (e.g., less than a college degree) were predictive of lower income among women, but higher levels of education (e.g., a graduate degree) were not predictive of higher or lower income among women. And among men, education level was not predictive of income at all. In other words, male advisors with less than a college degree did not earn any less than male advisors with an undergraduate or graduate degree.

Practical Takeaways From Our Gender Pay Gap Research

It is important to note that our two studies do not speak definitively about the gender pay gap in the financial planning industry. Our studies also have a number of limitations, such as a lower than ideal number of female participants and using a sample of Nerd’s Eye View readers that certainly does not generalize to the entire industry. Nonetheless, we believe our studies do still have some practical takeaways for advisors.

First, it is important to acknowledge that while we do see some material differences in income by gender, those differences, for the most part, do not seem to stem from unequal pay for equal work. Rather, we believe our studies provide some initial evidence suggesting that men and women are paid relatively equally in the industry when relevant factors are considered. Nonetheless, we cannot speak to whether men and women may not have equal participation in or access to those factors in their career journeys as financial advisors, so that is an entirely different dimension of discrimination that still needs to be examined.

Because we do not find evidence of unequal pay for equal work, we hope our studies will be seen as having inclusive implications from the perspective of encouraging more women to join the industry. While we do see differences in income between men and women within the industry, those differences, for the most part, were explained by differences in characteristics of the groups rather than differences in treatment. In other words, when we look at men and women with equal levels of pay motivation, experience, credentials, responsibility, and revenue production, we do not see women getting paid any differently than their male counterparts.

Furthermore, our study can provide some insight into the factors which do tend to be associated with higher income, as well as some that may need a closer look in the future. In particular, “riskier” career paths (i.e., paths which take on more variable compensation and risk of failure) and “leveraged” career paths (i.e., positions which allow advisors to spend more time focusing on servicing clients) appear to pay better than “safer” positions or positions without support staff.

That being said, our findings also indicate that career opportunities are very good even for advisors who may prefer a stable income and less career risk. After all, the lower average incomes earned by women ranged from about $165,000 to $197,000 between the two studies ($200,000 to $239,000, among men), an average income 5-6 times higher than that of the median personal income in the US.

If an advisor (regardless of gender) is happy with a role that pays $165,000 but carries more stable income, greater flexibility, or other non-monetary benefits, then it is not clear that they ‘should’ necessarily be chasing more income if it comes at a loss of general satisfaction or work-life balance.

We should note, as is always the case in research on group differences, that everything mentioned within this article only applies at the group level, and that any relationships observed at the group level should not be assumed that to apply to particular individuals.

For instance, while men in our study expressed more motivation for compensation than women, on average (potentially leading some men to choose career paths with more variable compensation that in practice often did lead to higher compensation in the long run), some of the individuals with the highest pay and strongest motivation by income within our study were women. Therefore, advisors should never assume group differences (e.g., men preferred variable compensation while women preferred stable pay) necessarily apply to an individual in particular. When interviewing a prospective job candidate, research on group differences does not tell you anything about the individual sitting in front of you in that interview.

Particularly in a context like job interviews, where individuals self-select into applying for certain positions with certain firms, there are even stronger reasons to assume that group differences would not apply to individuals. If an advisory firm has a reputation of being a place where people work really hard and make a lot of money, and another advisory firm has a reputation of providing more work-life balance, that’s not going to be a secret to people applying for positions. Candidates who prefer one environment over another will tend to self-select into different candidate pools that fit with their own preferences.

Potential Gender Challenges In The Industry Shift To Salaried Pay From Performance-Based Compensation

One interesting dynamic related to the financial advisory industry being dominated by performance-based pay is that this type of compensation actually limits a lot of the subjective discretion that managers could use to discriminate if they wanted to.

If everyone receives an equal payout based on a firm grid, then everyone knows what you need to do to earn $100,000, $200,000, etc. While there are still factors that could make the difficulty of reaching revenue thresholds unequal between men and women (e.g., the glass ceiling effect, performance-support bias), the revenue thresholds are what they are and do not change by gender.

As the industry experiences a shift toward more salaried compensation, this could actually increase opportunities for managers to engage in preferential treatment of employees for discriminatory reasons. For instance, whereas a payout based on revenue production is highly objective, giving raises based on more subjective evaluations of employee performance creates greater opportunities for managers to use discriminatory factors when deciding whether to provide a raise or not. Furthermore, challenges women face, such as gender differences in negotiation behavior (where women have been found less likely to negotiate aggressively for salary raises compared to men), could increasingly result in pay disparities that emerge as gender pay gaps in the industry’s more-salary-based future.

Challenges In Providing Family Leave

Findings from our follow-up study suggest that some decisions, such as taking family leave, may influence men and women in the advisory industry differently. As a result, another major challenge facing the financial advisory industry is how to handle family leave and other issues related to the unequal burdens of childrearing by gender. Addressing this challenge may not be as straightforward as many might initially suspect, as there are lots of unintended consequences that can complicate the effects of certain policies.

For instance, while purely anecdotal, some firms have encountered challenges with what seemed to be highly progressive family policies such as unlimited leave after childbirth. Similar to how unlimited vacation can actually discourage individuals from taking vacation leave, some firms have experienced that an unlimited leave policy actually results in less parental leave taken by employees.

A likely reason for this is that unlimited leave doesn’t help to set any norms for what to consider as normal or acceptable. If some individuals choose to take little or no leave, others who wish to take leave may fear that they’ll be seen as slacking compared to their peers. By contrast, when employees perceive a leave period as “reasonable” and are provided with more firm parameters defining that leave period, then they may be more inclined to actually take their leave.

Of course, while offering family-friendly policies can make employment benefits at a firm feasible for a large number of individuals, it still doesn’t necessarily mean that all individuals will take those policies up at equal rates. Some tech firms and international companies have been wrestling with these issues, with some choosing to adopt mandatory leave policies to promote greater gender equality.

However, there are still some complicated considerations, as incentives which are generous but not mandatory could result in unintentional discrimination against groups of individuals more likely to use those benefits (e.g., even if firm owners don’t consciously address it, they may hold a preference for employees they suspect are less likely to use a costly benefit), and mandatory leave policies could still result in unequal outcomes.

In a different study of mine (coauthored with Elizabeth Parks-Stamm; not yet peer-reviewed), men were far more likely to report intentions to use mandatory leave periods for purposes other than taking care of their newborn, and instead reported intentions to use leave periods for activities such as catching up on existing work, taking on additional projects, job hunting, learning new skills, exploring new business ideas, and even taking on additional paid work.

Many other academic studies have been conducted that illustrate the differences between men and women when it comes to family leave benefits. Some studies have found that family-friendly policies provide more benefits to men than women, while others have suggested that men and women may use their free time from family-friendly policies differently.

For instance, men may be more likely to be “inaccessible” and engaged in leisure activities with potential professional benefits (e.g., playing golf), whereas women are more likely to actually use their family-friendly time off from work for household labor that does not provide the same professional benefits. If that’s the case, then employee benefits that provide a service instead of time (e.g., employer-paid household cleaning services or childcare) may be more effective at creating equal opportunities for men and women to use their free time accordingly.

Of course, that’s not to say that family-friendly policies still aren’t a step in the right direction, but they may have complicated consequences and may not always actually reduce the gender pay gap (or gender leave gap) in the manner that is intended.

Financial Advisor Gender Pay Gaps: Employer Discrimination Vs Employee Personal Preferences?

When thinking about gender pay gaps, it is also worth considering whether eliminating gender pay gaps entirely should be the ultimate goal. Of course, any form of discrimination based on one’s gender, race, or other arbitrary characteristics should not be tolerated and eliminating this component of gender pay gaps should be a goal that is sought after, but what should we do when gaps arise due to gender differences in preferences or other decisions made under one’s free will?

Granted, we are likely a long way away from workplace policies and compensation models that are not influenced by other potentially discriminatory biases (biases which may stretch as far back as bias in the socialization of children), so there’s still a lot of work to be done. Nonetheless, the ultimate consequences of policies are often really hard to discern, and all sorts of unintended or surprising findings have come up in these areas of research. For instance, findings such as those highlighted by the “Nordic Gender Equality Paradox“–which refers to the finding that countries with some of the most egalitarian gender norms actually see some of the largest gender differences in career and other outcomes–continue to puzzle researchers. For example, some studies have found that while women in the US have a 15% lower chance of reaching a managerial position, women in some of the most gender-egalitarian countries are actually far less likely to reach such positions, including a 48% lower chance in Sweden, a 52% lower chance in Norway, a 56% lower chance in Finland, and a 63% lower chance in Denmark.

Nonetheless, to the extent that our research found that the largest driving factor was advisor preferences for compensation–with men more likely to be motivated by income (and presumably, therefore, pursue roles with revenue-based and other variable compensation), while women were more likely to be motivated by stable pay (and presumably, therefore, pursue salaried positions)–that finding raises significant questions about whether or how much the remaining gender gap is a ‘problem’ or simply a reflection of preferences. This may be particularly true given that women who were motivated by income did not show any gender pay gap in the compensation they received for their work.

On the other hand, it’s still possible that advisory firms may be able to do more to equalize opportunities across different preferences in the first place. For instance, if variable-based compensation roles had more ‘safety nets’ and family support than they currently do, might female advisors who are less likely to be motivated by income still be able to better take advantage of the long-term upside opportunities the industry provides to those willing and able to accept more variable compensation?

While our Kitces Research Studies cannot address all forms of discrimination in the financial advisory industry and should not be interpreted as suggesting gender discrimination is not an issue within the industry, we do ultimately feel that our studies should be seen as providing a positive message for women who are interested in careers in financial planning. At least on this one narrow dimension of potentially discriminatory behavior, our initial findings do not suggest men and women are paid unequally for equal work. And, if this means that women have less reason to fear being treated unfairly if they pursue a career in financial planning, then we hope that carries an inclusive message to help promote diversity within the financial planning industry.

Leave a Reply