Executive Summary

Over the past several months, life has become increasingly challenging for many, as we have collectively had to weather the pandemic, market instability, high unemployment rates, and social unrest across the country. Inevitably, people everywhere are experiencing high levels of stress and anxiety, and financial advisors are faced with clients who are stressed and worried about their financial plan and may need help to cope through difficult situations. One simple and accessible strategy to help clients deal with stress is by practicing gratitude, and financial advisors can leverage gratitude practices as a tool to help clients work through difficult feelings and circumstances around their financial goals.

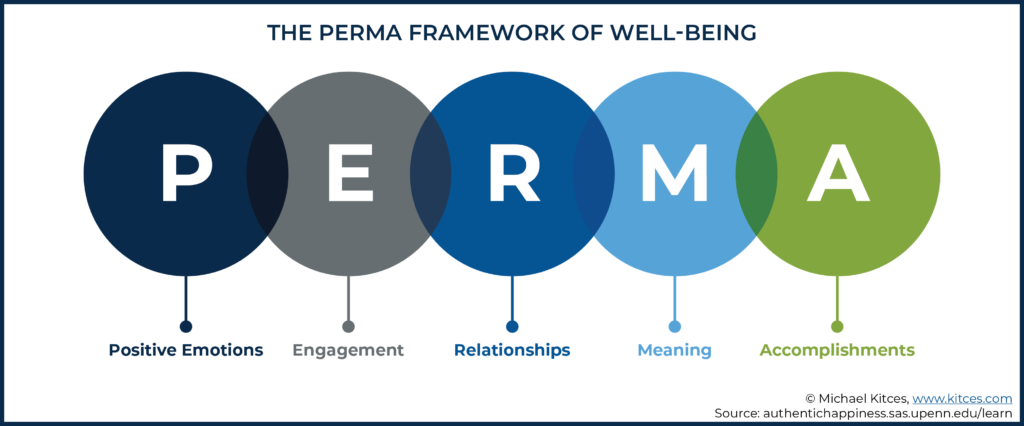

Financial planning conversations generally focus on future goals and events and are considered ‘private’ topics of discussion that often only focus on the client themselves. Gratitude, on the other hand, focuses on the present, by consciously acknowledging the cause(s) of some positive outcome that has resulted in current feelings of appreciation, and involves how external social factors have contributed to those feelings. Research has tied the importance of gratitude to general life satisfaction and how it embodies positive psychology models such as the “PERMA” framework, which identifies the key requirements for well-being: Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments.

Accordingly, by guiding clients to acknowledge gratitude in their financial planning conversations, financial advisors can help their clients feel better about current planning choices, and find satisfactory solutions to difficult problems. And by encouraging clients to recognize and practice gratitude in the present moment, financial advisors help those clients sustain patience for future rewards! Because when one feels gratitude for and thus can be comfortable with having enough to begin with, the desire to acquire or accomplish more is generally lessened.

Gratitude can also be a useful tool for clients to recognize how connecting with others can be valuable when it comes to their financial planning goals. For instance, simply having the advisor to talk to about their financial plan offers tremendous relief for many clients, not just for the technical planning guidance, but also for the social support that the advisor often provides to the client. Or encouraging a client who may seem unhappy or lonely to identify (and invest in) ways to build social connections can help the client achieve more life satisfaction. Simply having conversations that explore sources of gratitude can be very therapeutic for the client… and does not require the financial advisor to have any therapy training!

During client meetings, financial advisors can include gratitude practices in their discussions with clients by simply asking them to identify the gratitude they may have for their current life situation in general, or the gratitude they may have for other people. This can be done by using simple exploratory questions, such as, “What are three things you currently think you (or your partner) do(es) well financially?” or, “Describe three financial things you feel content about right now?” Gratitude practices can also be incorporated into client events, which can include group activities or discussions about how clients experience gratitude.

Ultimately, helping clients acknowledge gratitude can be a very effective way for advisors to ease their clients’ minds about troubling situations around their financial plan. And, while gratitude practices won’t solve all problems, they do provide clients a simple yet powerful strategy to cultivate more awareness of the important things in life that provide comfort, happiness, and satisfaction, but that are often taken for granted and easy to forget… and in the process, can reduce money disputes and help clients feel satisfaction that they really have ‘enough’.

Gratitude Is Present-Focused And Social, While Personal Finance Is Often Future-Focused And Private

Gratitude is the feeling of appreciation that comes about for someone (or something) that has, in some way, contributed to some positive outcome, and has two key characteristics.

The first is that it focuses on the present. Now, that may not sound revolutionary, but thinking about gratitude in this way helps us to distinguish it from similar concepts such as optimism or hope. Optimism or hope, like gratitude, may involve appreciation and positivity, but they are future-oriented emotions, unlike the present-based focus of gratitude.

Gratitude’s second important and distinguishing characteristic is that it is social. For example, in the definition provided by Harvard Medical School, gratitude involves “recogniz[ing] that the source of that goodness lies at least partially outside of themselves. As a result, gratitude also helps people to connect…”.

And now that we have a better understanding of gratitude, it will be easier to work with it (as discussed later in this article) as well as understand its connection to well-being – the crux of why gratitude is important to a well-balanced financial life.

For instance, through positive psychology studies, researchers have uncovered that gratitude is very important to general life satisfaction. The reason for this is that gratitude may be intertwined with each piece of the PERMA framework (Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments) developed by Dr. Martin Seligman, which serves as a cornerstone in the positive psychology movement. While traditional psychology tends to focus on healing or surviving, positive psychology focuses on well-being and thriving. Moreover, the pieces of the framework help us consider the key ingredients for moving beyond just living to really enjoy our lives by cultivating a deep sense of fulfillment.

In the context of the PERMA framework, gratitude is indeed a Positive Emotion. Expressing gratitude involves being presently focused, which is key to true Engagement. Expressing and receiving gratitude is also an important part of healthy, fulfilling (i.e., Positive) Relationships. Gratitude can even be a part of Meaning and Accomplishment, as both may involve social networks.

Example 1. Lucy, a financial planner, has a deep passion for providing young adults with financial education. As such, Lucy and her team volunteer every year to go into local high schools and teach the students about student loans, basic budgeting, and savings.

Lucy feels personally accomplished for having built these inroads with the local high schools and working closely with her team on this mission.

She feels an even greater sense of meaning, sharing what she feels is her life’s mission with others.

The same goes for more specific aspects of our lives, such as our relationships. Feeling appreciated by our friends, family, or loved ones and feeling gratitude for our relationships, fosters an increasing sense of our individual well-being.

And gratitude also plays an important role in relationships when it comes to financial support. Consider the findings in the study by Byers, Levy, Allore, Bruce, and Kasl in 2008, in which the researchers found that an adult child’s expression of gratitude toward their parents for continued financial support had a direct relationship with the parent’s psychological well-being.

Not surprisingly, when the children expressed gratitude, the parent’s psychological sense of well-being went up, perhaps from the sense of reward (and their own ensuing gratitude for being appreciated by their children) that they receive from their child. Maybe this is why (or at least partially why) financial planners often see clients (parents) supporting their children; if the child expresses gratitude for the financial support…it can feel very good to give, and perhaps may even be a reason why some parents may find it difficult to stop giving to their children.

Financial advisors are also likely to see connections between gratitude, money, and relationships when working with couples. In addition to the obvious financial aspect of marital disputes involving money (e.g., not enough money, too much money), they often also have over-arching appreciation or gratitude issues tied to them.

For instance, a number of research studies from the ’80s and ’90s found that women’s earnings are at times downplayed – women “help” bring in money, but their money is considered nonessential or only for “extras”. Said another way, these studies highlighted the fact that women are at times not considered dual or co-providers, which may leave certain female earners feeling unappreciated by their partner.

And certainly, men can experience feeling unappreciated as well. For example, they work tirelessly to support their family, but in doing so, they miss time with them and perhaps time is what the family really wants – it is often hard to strike a balance between work and family, for both men and women. And it is hard for both to have these conversations.

Example 2. Laura and John, a married couple, are fighting over how to spend John’s bonus. Laura wants a family vacation. John wants to buy a new family car. They have decided to turn to Michael, their financial planner, to be their tiebreaker.

Yet Michael, on top of knowing that taking sides is not smart, also really wants Laura and John to save the bonus. Laura and John had promised to save the bonus six months ago, but it is clear that times have changed now that the money is in their hands.

Thus, avoiding a three-way fight, Michael opts for higher ground and knows that, to get everyone swimming in the same direction, he has to get to the bottom of what Laura and John are really feeling – what is driving their impatience?

In some strategic back and forth with Laura, Michael uncovers that Laura, a stay-at-home mother who absolutely appreciates that John works hard to provide for her and their two kids, struggles with feeling appreciated herself and feels that a vacation would be a satisfying way for her to get recognition for her (unpaid) work around the house and to give her a break. When John says he doesn’t want a family vacation, Laura hears that her work and time with the kids goes unnoticed because it is not paid work.

And after a bit of back and forth with John, Michael learns that John also feels underappreciated. John feels that his attempts to care for the family go unnoticed because they are oftentimes more ‘practical’ than ‘fun’. John wants to get a new car for the family because he has heard Laura complain about the current car many times. It is hard to get the kids in and out of their current car, and she does not feel very safe in their vehicle. John knows a vacation would be more fun, but getting a new car for Laura and the kids would keep them safe and hopefully a little happier as with the new car, it would be easier transporting the kids while running for groceries and taking care of other errands.

Yet, even with all of this probably making perfect sense…the reality is that the components of gratitude (i.e., its social basis and focus on the present) are not generally integrated into conversations about money. In fact, most of the social conditioning we receive is to the exact opposite – we are often taught that we should not be present-focused or social when it comes to money!

Take, for instance, the ‘best’ financial decision-maker. In economic theory, this person is a rational, self-interested maximizer that focuses on the future – nothing social or present-focused there. From financial therapy research, like that on money scripts, we often see individuals struggling with the two gratitude constructs. For instance, in the Money Vigilance script, people don’t believe one should talk about their money and, instead, keep their thoughts and feelings about money hidden, which would be the opposite of being social. Money worshipers believe that more money is always better. Said another way, Money worshipers are clearly not presently satisfied with their current financial situation.

From a social conditioning perspective, the results from these research studies on money scripts suggest that it is very unnatural for people to feel or even think about feeling gratitude in relation to their financial situation. Said another way, as we grow up, we do not often receive, and therefore do not learn and internalize positive, present-focused and safe social messages about money.

Instead, we learn that money is to be saved for the future, which might make us feel guilty or shameful if we use it when we have it (even if we really need to use it!) in the present. If we can recognize that we are comfortable using our money in the present, that may also feel a bit strange.

For example, what would you think of a client who came into your office and said they felt totally good and 100% comfortable with where they were financially and weren’t concerned about saving for the future? Would you think that perhaps they lack the drive to plan for retirement and any long-term goals? Would you think they were full of themselves, having made so much money? Who needs to work…right?

In today’s world, very few people know how to feel or express gratitude for their current financial situation, at the risk of sounding complacent or snooty – and that is not a good thing because, as it turns out, if we were a bit more appreciative of current circumstances, we might actually be better at achieving our future goals!

The Therapeutic Value Of Gratitude Doesn’t Require A Therapist

As paradoxical as it may seem, gratitude’s focus on the present actually helps to sustain patience for future rewards, as researchers DeSteno, Li, Dickens, and Lerner found that gratitude reduced feelings of impatience. Additionally, Dr. Derek Tharp has shown that more, and not necessarily less, emotion is beneficial for good financial decision-making; this rings especially true as applied to gratitude.

When we think about it, these findings make total sense. If we are comfortable with where we are in the present and feel both financially and emotionally content with all of our needs being met, then we would be less concerned about spending money in the present to find ways to deal with the emotions that often come up – such as the impatient feelings that arise when working on a particular goal – because those feelings simply wouldn’t exist in the first place! And this is revolutionary to consider in the context of how financial advisors work with their clients.

Basically, would you want to try to fight impatience and tell clients what they need to stop doing? Or would you prefer to cultivate a sense of well-being that wards off impatience to begin with?

While advisors might help their clients set great future goals in the hopes of motivating them to save today, future goals are easily derailed in the present. (For example, clients who get an unexpected bonus are often naturally inclined to spend it instead of saving it).

Instead, it may be more important (or at least equally important) to help clients recognize that they have all that they need right now to enjoy a great life – they can afford to save because there is nothing that they are really pining for at the moment that they feel needs to be solved with spending.

In other words, it turns out that one of the best paths to having the patience to accumulate more is to get comfortable with having enough to begin with – and learning how to guide clients to this frame of mind does not require any therapeutic training!

Example 3. Returning to John, Laura, and their financial advisor Michael… now that Michael has uncovered some of the underlying issues – neither spouse is feeling appreciated/expressing gratitude in the way that the other spouse needs it – he simply encourages Laura and John to brainstorm some solutions and ideas to express gratitude to and for one another. And their conversation went a little something like this:

After some back and forth discussion, Michael gently reminds them of their prior commitment to save the money while repeating back to them their individual needs and says to the couple, “Correct me if I am hearing you both wrong, but it sounds to me that this is not really about spending John’s bonus. If I may, and again tell me if I have misunderstood but, it sounds like this is more about trying to show each other that you care for each other – John, you want the car because you want to take care of your family. Laura, you want a vacation because you want some relaxation time with Michael and your kids.

“This is a great problem to have; you all have a strong desire to care for each other.”

“I am not really sure this is truly about spending the bonus on either the car or the vacation. For example, we could return to the original plan to save the bonus, at least most of it, and think of a mutually agreed upon expression of gratitude.”

Laura and John look at each other and agree, so Michael continues, “I encourage you to save the bonus as originally planned, and let’s spend more time talking about what we can do today to create some sustained contentment and appreciation – a plan that you both like and agree to.”

The other important consideration coming out of the study by DeSteno et al., (as well as from Dr. Derek Tharp’s research) relates to willpower, which is an exhaustible resource. Basically, there is a reason why advisors might find themselves reaching for a cookie, piece of cake, or candy after taking a Kitces CE quiz. All of your willpower was exhausted reading through the articles and answering the challenging quiz questions, so you actually find yourself unable to say no, using even a little more willpower, to those cupcakes in the kitchen.

Refer back to Laura and John, who had originally promised to save that bonus in anticipation of the bonus, but were unable to do so when push came to shove. Clients might actually start out strong initially, sticking to new habits or commitments, but over time often revert back to their old spending habits, especially if they’re struggling with additional stress and exhaustion from the frustration of feeling unappreciated or lacking gratitude.

It is really hard to sustain willpower over time, let alone through tough spots. For example, COVID-19 (it is hard to feel grateful for anything under a mountain of uncertainty and chaos), bad market timing (where hard work to stay in the market may not feel appreciated), job changes (maybe because you didn’t feel appreciated), life changes (which can be difficult to forge and feel appreciated because things are happening too fast), or persistent unappreciation are all situations that pose extreme challenges to an individual’s motivation to stick to their initial money decisions.

And this is perhaps where the other part of gratitude can come in – the social part.

Life, and its many transitions (good and bad), can be really hard. And in the same way that gratitude can act as a substitute for willpower to get us through times of change and indecision, gratitude can also help us to share responsibility, feel less disconnected and isolated, and get us the help we need to sustain ourselves.

Is isolation or being alone such a bad thing, you might ask? And the answer is yes, it really is bad. Humans are social creatures; even those of us (myself included) who are highly introverted still need to somehow feel socially connected. What is more, numerous psychology studies have highlighted the dangers of isolation and feelings of disconnection.

As just a couple of examples at least peripherally related to financial planning, research has found that individuals in their “golden years” (retirement years) actually commit suicide at higher rates because they feel lonely. Another preliminary research study from Piehlmaier, Warmath, and Robb in 2018 found connections between investor overconfidence and isolated decision-making, showing that sharing decision-making lowered overconfidence. And other research findings often partially blame isolation for financial scam scenarios in elder populations. Basically, when we feel alone and isolated, shouldering the burden of life by ourselves is difficult, and people will often make poor choices.

Another way to think about gratitude, positive psychology researchers refer to gratitude as ‘social lubricant’ as it ‘greases’ the tough spots we find ourselves in and helps us to connect and find the strength, in places outside of ourselves, that we need to keep going, much like greasing a hinge on a door so it can swing more easily along its course.

And as one might imagine, there is a fair amount of research finding that gratitude practices are helpful, as evidenced by a recent meta-analysis. And even in the instances when they may not be as effective, as an earlier meta-analysis points out, they are not hurtful. For example, two longitudinal studies by Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, and Joseph in 2008 found that gratitude was uniquely responsible for feeling supported and had a direct relationship in lowering stress and depression when looking at freshmen entering college. Now, certainly entering college may not be as stressful as entering retirement, but this study is highlighted here because of its longitudinal design.

Longitudinal studies follow the same person and compare them against themselves at different points in time (which is distinct from a cross-sectional study, which compares two different people from different groups at the same point in time). This is important because longitudinal data actually establish causality – and in longitudinal studies that actually measure and pinpoint cause, not just relationship, showed that gratitude caused a positive impact.

In contrast, cross-sectional studies compare two different people (or groups) at the same point in time and only describe relationships, so cross-sectional studies examining the effects of gratitude may not be as insightful as to how they actually affect a person’s outlook. Gratitude is a personal experience, and we are not in competition with anyone when we practice it; thus, cross-sectional studies do not identify how gratitude affects an individual over time.

These findings that gratitude can have a unique and important positive impact during difficult life transitions support other studies with similar findings that use different research designs. For instance, work from Sarah Asebedo in 2017 used the PERMA framework (which we know encapsulates gratitude) to demonstrate how psychosocial factors can positively contribute to financial self-efficacy. For instance, positive relationships with family (and with a spouse, in particular), generally positive emotions, feeling or having meaning in one’s life, and feeling accomplished all positively related to financial self-efficacy.

Thus, the first way advisors can use gratitude with their clients is to actually help them focus on connection. In our example, Michael helped his clients to connect with each other, but the focus can also be on connecting with the advisor, themselves. Individuals who have someone to discuss their finances with often make better decisions; they tend to avoid scams and maybe even feelings of loneliness, as their advisor may notice right away when a client is struggling and can frame a conversation around the client’s financial plan to encourage the client to find something like a new hobby that helps them establish a social network.

And it doesn’t require any therapy to simply talk through a client’s questions or encouraging them to spend more of their money on building social connections. Researchers Wood et al. concluded from their work that “giving people the skills to increase their gratitude may be as beneficial as such cognitive-behavioral life skills as challenging negative beliefs.”

Which means that there is a way to be therapeutic without engaging in therapy and that gratitude can offer this powerful tool as a way to move forward when clients get stuck.

Three Gratitude Practices That Financial Planners Can Implement In Their Firms Today

Gratitude is really the bee’s knees, as it is an immensely powerful tool that can be implemented without any special training. Gratitude practices can also be relatively simple –just about everyone can recall a parent or guardian from their childhood telling them to “count their blessings”. And I am happy to report that developing gratitude, for the most part, is just that simple!

For example, research on gratitude has found that three simple practices that anyone can do can serve a lot of good:

- Jotting down 3-5 things you currently feel grateful for;

- Writing a letter to someone (or yourself) expressing the gratitude and appreciation you feel for that person; and

- Keeping a journal (especially one dedicated for noting your feelings of gratitude – i.e., a gratitude journal).

So how might these ideas be applied to a financial advisor’s client relationships? In order to answer that, it is useful to look at how different groups of clients might be addressed.

For example, talking about gratitude with new clients and returning clients can be done during regular 1-on-1 client meetings. For clients who may be going through a difficult life transition (and also as a way to reach out to clients en masse), it may be helpful to have voluntary group events that give clients the option to drop in and participate, based on their own comfort level with respect to sharing their thoughts about gratitude. Clients can be encouraged to try some of these gratitude practices:

- Express gratitude for their current life situation in general;

- Express gratitude toward other people in (or outside) of the group; or

- Explore some of the positive qualities about their current financial situation.

Advisor-Client Gratitude Exercises For 1-on-1 Meetings

When meeting with a financial advisor for the first time, new clients do not know their advisor, and their financial advisor does not know the client. This may be a good opportunity for the advisor to use a little gratitude practice to help them get to know their new clients.

For example, as part of the initial data-gathering meeting, the advisor can take the time to ask questions that encourage clients to identify sources of gratitude. The set-up might look something like this:

Example 4. Jen and Tom are new clients for Michael, their financial planner. Michael has just spent the first 45 minutes of their meeting learning about Jen and Tom’s goals and going over some basic financial statements.

Before bringing the meeting to a close Michael decides he wants to reinforce the groundwork toward Jen and Tom’s goals with a little gratitude in the here and now, so Michael says, “Jen and Tom, I have really enjoyed our time together today, learning about where you want to go. I can see financially where you are from your financial statements, but I also want to know how you view yourself – not just using the numbers.”

He then asks the couple the following questions:

- Tell me, individually, what are three things that you currently think you do well financially?

- Give me at least one thing that you think your partner does well financially?

- Describe for me three financial things that you feel really content about right now?

Michael uses these gratitude-based questions to ensure that Jen and Tom leave the office not only with big plans for their future but also with a sense of contentment with the present moment that will help to keep them on track.

Michael, now knowing this information about his new clients, can also use it in future discussions to perhaps remind them of the positive traits that they see in themselves and one another when things get tough.

Actively developing gratitude is great not only for new clients but also for clients who may have already been on board for a long time. Essentially, there is never a bad time to start practicing gratitude, but how you go about it for existing clients might look a little different from starting the dialogue with new clients.

For instance, it is probably common with ongoing clients to start your meeting with a simple greeting like, “How have you been?”. This is perfectly fine, but giving it a slight ‘gratitude twist’ might liven things up a bit without making ‘doing a gratitude practice’ super-obvious or awkward.

Example 5. Devin and Frank are long-time clients of their financial advisor Michael, and it is time for their yearly review. Instead of starting the meeting with the typical, “What’s new in your life?” question, Michael decides to focus on fostering gratitude in his dialogue with his clients.

Michael greets his clients and as they sit down, he shuffles some papers, leans in a bit toward them, and says with a smile, “So, share with me three good financial things that have happened since our last meeting.”

Devin and Frank take a moment to answer, and Michael knows that whenever he starts a ‘question’ with a command (share with me/tell me/describe for me), his clients often pause, so he waits patiently for their response.

Devin and Frank finally answer, and Michael smiles again and says, “Wow, that is great! Thank you for sharing.”

Michael then continues, “Since you have some great stuff going on, tell me what you are currently feeling very content about financially?”

Basically, gratitude can serve as a good way to start or end a meeting. It does not have to be a big to-do. Small, simple requests that purposefully bring the mind into the present and orient it toward the positive are all that you need.

Advisor-Client Gratitude Exercises For Clients in Transition (Via Gratitude Group Gatherings)

Broaching gratitude with clients in a major life transition is a little different from starting the conversation with those who are not experiencing any big changes, and when it comes to how (or if) gratitude really helps someone in a serious life transition (although we know with certainty it doesn’t hurt them), the jury is still out.

As an example and as mentioned earlier, studies have shown that those going through a divorce were no worse off, but no better off either after a gratitude intervention. On the other hand, different studies have documented that using gratitude practices after having recently been diagnosed with a disease was helpful.

Moreover, instead of trying something that may feel awkward (for example, telling a client to write a “gratitude letter” when they are really struggling with an ugly divorce or being diagnosed with cancer), deploying gratitude to the masses (i.e., available to all of your clients collectively), recognizing that those who are ready and open to having the conversation (e.g., clients struggling with transitions who really are ready to engage) will come on their own terms.

As discussed throughout this article, transition is hard. During a difficult transition, it is easy to get lost and feel isolated. Deploying gratitude in groups can bring people together, fostering a sense of community and avoiding feelings of isolation. A group event also creates an opportunity to work together on a project that brings the group’s focus to the present moment.

And in contrast with the previous two examples involving new and existing clients, where the gratitude practice is used in place of a traditional meeting close or opener, gratitude here can be more effective if used by the advisor to frame the upcoming event in an obvious way. Said another way, in the first few examples, the advisor was actively leading his clients to establish a sense of gratitude for each other through a discussion of their specific issues in the moment, but never actually broached the idea of having the discussion beforehand.

In the following example, however, clients are voluntarily attending a gratitude event where the discussion and exercises are free-form and collaborative. The clients are asked to attend the event in an obvious way and can decide how to use the discussion and exercises to focus on what seems to them to be most beneficial.

Example 6. Michael feels like he has had a lot of tough clients lately, with concerns about COVID-19, divorces, and bad health. Thus, instead of trying to create more individual time for each of his clients, Michael decides to invite everyone to participate in some gratitude activities via video conference.

Michael advertises the event as a fun, TED Talk-style presentation followed by group/family gratitude exercises where everyone can take stock in the things they are grateful for. Michael plans to have a local marriage and family therapist offer a live video talk about the benefits of gratitude and conduct a few follow-up exercises.

To close out the meeting, individuals and families can choose to take part in a gratitude sharing circle, going around the virtual room to simply say what they are thankful for that day or in the past week – not necessarily future- or past-oriented.

It is okay if some of this is sounding a little odd – in fact, the weirdness you may be feeling is super normal (and well documented in research). Basically, people describe feeling shy, embarrassed, or awkward about doing these things, probably again (sadly), because we have not been socialized to do them. Moreover, this oddness can and does exist, this is why you might not announce to a client, “hey, we are going to do a gratitude thing now”, in a 1-on-1 meeting. You would probably get push-back, so it is likely easier to introduce it in simpler, command-style ways so that they client won’t necessarily think anything about it as it is happening.

All that being said, awkward or not, I want to point out that I am a firm believer in the power of gratitude as I have a gratitude practice of my own (and so does Oprah Winfrey, by the way!).

My own gratitude practice, which I admit felt a bit weird when I started, I do with my husband. Every Friday, we discuss five things we are grateful for that week – he gets five and I get five. Sometimes we do this through email as he is on active duty in the military and is not always around. These gratitude moments can be about anything – work, exercise (or delicious cake!), our little one, something we learned, or just something that happened.

About once a month, we also write gratitude letters to or for the other person. These letters are nothing long and not even necessarily romantic. It is just a time to tell the other person (which could be anyone in your life: friend, spouse, co-worker, sibling, parent) that you see them and care about them, AND that you allow them to express feelings of gratitude toward you too. You, too, deserve to hear and honor that someone is grateful for you!

This practice does not solve all things, but similar to the research, I have found that it ‘greases’ the difficult spots. Recently, COVID-19 has posed a real challenge. This small practice has been a way to see the light and create a little stability even when things feel totally crazy.

All of these practices and suggestions apply to everyone, including financial advisors themselves. Things can be tough out there. Taking time out of each day to count your blessings or to write a nice hand-written letter to a client that you want to thank for a referral or just because they said something that warmed your heart are both excellent ways to bring about gratitude in your own life.

Leave a Reply