I almost slipped and bought into the SPAC Renaissance. Almost.

Draftkings looks legit. But Draftkings could have been a true IPO. The SPAC wrapper was beside the point. Chamath and Ackman will probably do something legit, those guys usually find a way to win. Maybe a few others. The rest are / will be garbage. My first impression was right.

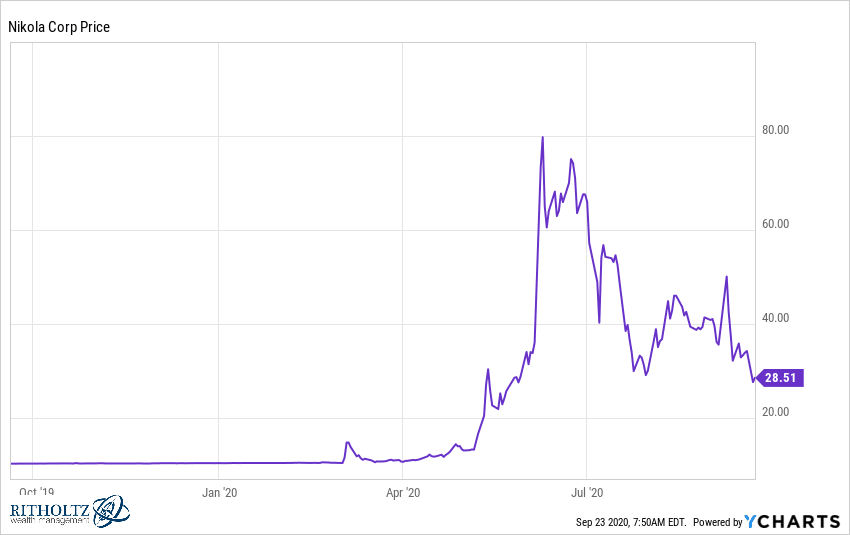

Nikola’s stock has now fallen from near 100 down into the 20’s as the guy’s whole story has unraveled. Then the guy stepped down and ran away. None of this had to happen. But Nikola arrived on the markets as the quarry of a Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicle and the hype drowned out the diligence.

In a traditional IPO, you go public by crisscrossing North America (and sometimes Europe and Asia) sitting in front of investment bankers, syndicate personnel, pension fund managers, mutual fund portfolio managers, investment committees, NYSE and Nasdaq exchange officials, family office CIOs and hundreds (sometimes thousands) of other intelligent, skeptical, well-trained professional investors to explain your business. It’s called a roadshow and it’s f***ing grueling. It should be grueling. That’s the point. It’s called vetting.

By selling your company to a SPAC and then taking over an empty shell that’s already public, you skip most of this experience. You only need to convince one investor instead of thousands of investors to fund you. And that one investor – the guy who raised capital in the SPAC – he wants to believe! It’s the opposite of vetting.

The vetting takes place post-deal, when the stock market has its chance to tell you what you really are. It can be a very violent public bloodletting. For Nikola it certainly was.

I wonder if NKLA would have made it through a traditional IPO roadshow. Maybe, but as a small cap IPO from a third-tier brokerage firm. It reminds me of some of the deals I’ve seen placed in my bucket shop days. But in the Big SPAC Era they got the red carpet treatment right away. Never paid any dues. Never had to convince more than a few people that they were legit.

And then they did have to. And it didn’t go well.

Not enough eyeballs early on. Not enough questions. Pure belief until it was too late.

***

On a livestock fair in late Victorian Plymouth, England, a statistician with the name of Francis Galton asked around 800 attendees to guess the weight of an ox that was on display. He then calculated the mean of all estimates, which ended up being 1208 pounds. To his surprise, the measured weight of said ox was 1197 pounds, which put the mean estimation at ~0.01% off from the real weight. As Galton himself noted¹:

“…the middlemost estimate expresses the vox populi, every other estimate being condemned as too low or too high by a majority of the voters”

This effectively means that as a group, or as a collection of independent thinkers, we are very, very good estimators.

***

A jar of jelly beans.

How many jelly beans are in the jar?

5 guessers is not as good as 50 guessers.

500 guessers would be better.

SPACs have 5 guessers setting the value. IPOs have 50. The secondary trading on public markets is analogous to 500. 500 guessers will do a better job of estimating the number of jelly beans than 50 or 5 will. Run the test yourself.

F***, now I want jelly beans.

***

Michelle Celarier went off this week. Off. Her SPAC Boom story for Institutional Investor is epic. All her stories are epic. Especially the ones starring Bill Ackman, who has been coldcalling some of the most well-known pre-IPO unicorns to stuff into his SPAC – AirBnB, Stripe, etc. They don’t need a SPAC. They’ll do massive IPOs and get vetted to death through the traditional channels and still come out of it better off on their own. Thanks for lunch, Bill.

Anyway, here’s Michelle with a stat you should know:

Since 2015, the 89 SPACs that have completed mergers have an average loss of 18.8 percent (and a median loss of 36.1 percent), compared with the average aftermarket gain of 37.2 percent for other IPOs through July 24, according to Renaissance Capital, which tracks IPOs. Only 29 percent of the SPACs had positive returns.

No vetting until it’s too late.

Read it:

***

Here are some pro-SPAC arguments I am sort of sympathetic to but not really:

“Electric vehicle companies need to go public via SPAC because they’re experimental and have no revenues or established businesses yet, a traditional IPO doesn’t make sense.” Oh, tell that to the thousands of experimental biotech companies that have been doing IPOs for 30 years.

“SPACs speed up the process and don’t waste 9 months with the whole syndicate process.” Oh, cool. How’s that working out? May I introduce you to Michelle?

“If you’re invested in the SPAC and you hate the deal they announce, you can just vote against it or sell your shares!” True, but this is premised on a world in which every announced SPAC deal gets an automatic pop in the share price. You want to bet that continues forever? You think if there are 50 more of these publicly traded piles of cash lying around they’re all getting pops? Because there will be 50 more. It’s too easy. And the ducks keep quacking. They’re going to drown us in SPACs.

“If it’s a bad deal, the institutions and hedge funds will vote against it.” So if it’s a good deal, why not just buy in then?

***

“Should I buy SPACs?” I was asked by a 25 year old first-year investor on the air this summer. I said he should buy companies he would want to be invested in. Some companies that come public via SPAC will work out. Once the market has vetted them. Some won’t. Whether or not those companies were originally SPACs will lose relevance over time. It’s the same question as “Should I buy IPOs?” Well, which IPOs? Try to only buy the ones that go up in the future, I guess?

SPACs aren’t an asset class, like REITs or Muni Bonds or Commodities. They’re a tool to bring a company public.

IPOs are tools also, they’re not an asset class.

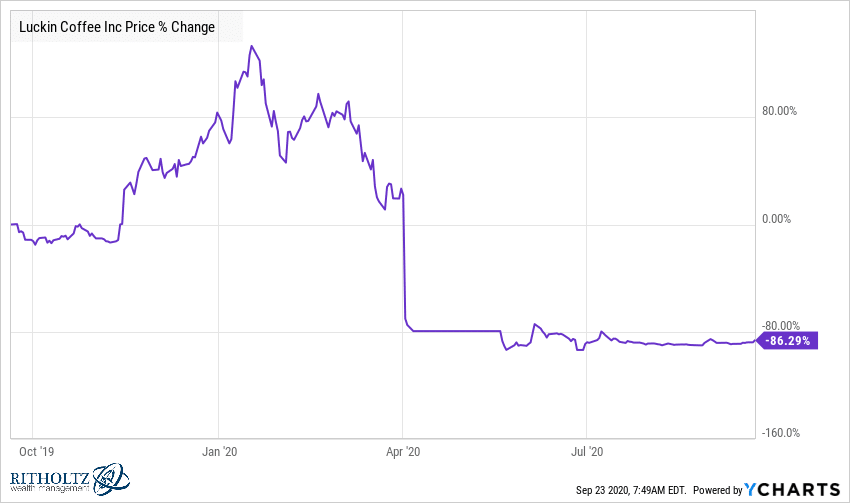

You can slip a terrible company through the IPO process too – like Luckin Coffee. Due diligence can scare people off from bad business models, but it’s not 100% foolproof in detecting fraud. Luckin Coffee, a Chinese based competitor to Starbucks, was formed in 2017. In the spring of 2019, the COO began faking sales and foot traffic and delivery stats. It went public in the summer of 2019 the traditional way – an IPO listed on Nasdaq – based on these artificial sales numbers and managed to raise $561 million. By January, they were selling even more shares to the public in a secondary, raising an additional $381 million. It was then revealed that half of the company’s $730 million in sales were fabricated. The stock lost 85% of its value in a single trading day.

How’d that happen? Outright lies:

Luckin Coffee sold vouchers good for tens of millions of cups of coffee to entities that had a relationship with the company’s chairman and major shareholder Charles Lu. One example includes Qingdao Zhixuan Business Consulting Co. that bought up to $134,000 worth of coffee vouchers in one order. The company made more than 100 similar purchases throughout the back half of 2019, according to WSJ.

Qingdao is not only linked to a relative of Lu, but an executive at a company Lu previously founded, and to a Luckin Coffee executive.

Individual Luckin Coffee employees were also part of the scheme which was traces back to before the company’s May 2019 IPO. Employees used individual accounts of customers to buy vouchers for multiple cups of coffee. The employees fabricated the equivalent of $28 million to $42 million in sales.

The documents also pointed to a made-up employee called Ms. Liang who processed more than $140 million of payments for raw materials and human resources services, according to WSJ. Luckin Coffee’s CEO Qian Zhiya personally approved the payments, often checked in on the status, and ensured the payments aren’t seen by the chief financial officer.

Investing in newly public companies involves risk – SPAC or IPO, it doesn’t matter. Especially companies with stories that may be too good to be true. And if they were formed in just the last year or two this is especially true. SPACs remove a layer of scrutiny in the early stages that may screen out some of the worst offenders before they can suck the public in.

Nikola was founded in 2014 and came public as more of a business plan than a business. They had the shell of a fuel cell truck without a fuel cell that could actually propel it. They had a groundbreaking ceremony for a manufacturing facility without having actually built the facility. Raw land in Arizona. They had big ideas and lots of chutzpah. Showmanship! It worked for Elon, why not me?

The imprimatur of General Motors entering into an equity investment and manufacturing relationship with the company was impressive for two days. And then a shortseller documented dozens of instances of the company making false or inflated claims about their tech. And sentiment turned on a dime. Many of the shortseller’s questions could have been asked during an IPO roadshow by investment professionals who think critically about these things for a living. And if they had, you may have never heard of Nikola, because they wouldn’t have gotten past the gatekeepers. Or they would have, but years later after having been funded privately and forced to actually build something. But the SPAC deal leapfrogged over that process, so it all had to be done out in the open waters of the public market.

It was a needless bloodbath. How many more of these are necessary?

Leave a Reply