Executive Summary

For many financial advisors, Social Security retirement benefits are often an integral part of their clients’ retirement strategies to provide income. However, married couples not only have their own retirement benefits that are calculated based on each person’s individual’s work history (assuming they have the requisite 40 quarter-credits of earnings) available to them, but can also take advantage of spousal benefits when an individual’s spouse has a work history that leads to a benefit greater than their own retirement benefit. While the spousal benefit is often advantageous to the extent that the work history of an individual’s spouse leads to a greater benefit than the individual’s own retirement benefit, it does lend to potential strategies for married couples to maximize total Social Security benefits that are not available to single individuals.

The amount of an individual’s Social Security retirement benefit that would be received at Full Retirement Age (FRA; 66 for individuals born in 1954 and thus reaching that age in 2020) is the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) and is calculated based on a formula that takes a certain percentage of the wage-inflation-adjusted average of the worker’s highest 35 years of FICA- or SECA-taxed earnings (i.e., the Average Indexed Monthly Earnings, or AIME). While the retirement benefit is equal to the PIA when a worker claims their benefit at FRA, benefits are reduced if they begin prior to the worker reaching FRA and increased if taken later (up to age 70). By contrast, an individual’s spousal benefit is equal to 50% of their spouse’s PIA. The spousal benefit is not adjusted if the working spouse claims the benefit early (e.g., if the working spouse begins taking retirement benefits before reaching FRA), but the spousal benefit is adjusted lower if the non-/lower-earning spouse claiming the benefit does so before their own FRA.

A business owner who is married may have the flexibility to hire their spouse and ‘transfer’ a portion of their salary between themselves and their spouses (assuming that the spouse actually provides services to the company to earn a salary in the first place). While this can serve to increase the couple’s combined retirement benefits, it often results in lower combined overall Social Security benefits for the couple! Notably, without shifting any salary, the non-/lower-earning spouse is already entitled to a spousal benefit. Accordingly, shifting salary away from the higher-earning spouse will often reduce their PIA right away (unless they already have 35 years of higher wage-inflation-adjusted earnings or, after the split, they continue to have earnings in excess of the maximum amount subject to FICA taxes for the year), while the benefit that the non-/lower-earning spouse would be entitled to won’t increase until their own retirement benefits exceed the spousal benefit that they would have received absent any changes.

In situations where a married worker receives compensation higher than the maximum amount subject to FICA taxes, cumulative Social Security benefits to the couple can potentially be increased by splitting the business owner’s salary between spouses. The caveat, though, is that by shifting the higher-than-FICA-maximum compensation to a lower-earning spouse, there can be a significant increase in annual FICA tax liability. In many – and perhaps, most – cases, the downside of the increase in FICA taxes will more than offset any cumulative increase in potential Social Security benefits. Thus, such an approach typically does not benefit a couple.

There are, however, situations where splitting the business owner spouse’s salary can make sense. One such situation is when a worker’s annual compensation will not be included in one of their top-35 years in calculating their Social Security AIME. If such is the case, and the worker’s compensation to be split is below the maximum amount subject to FICA, it may be possible to increase the spouse’s retirement benefit such that it exceeds their spousal benefit, thus netting a higher overall Social Security benefit for the couple (and without impacting the total FICA tax due)! Additionally, shifting compensation from a higher-earning spouse to their lower-earning partner will result in increasing the lower earner’s PIA. And with a higher PIA, calculated from the AIME based on the lower earner’s own work history, the individual’s retirement benefit will be commensurately higher, with the flexibility to claim those benefits as retirement benefits whenever they desire (versus being required to wait until the higher-earning spouse decides to claim their own benefit, which would only then allow them to claim their spousal benefit). And while the net retirement benefit amount may not be higher, it may be the couple’s particular situation where flexibility to claim the benefits is more important.

Another situation where salary splitting may make sense for a married couple is if one spouse earns less than the other, but their own retirement benefit is already close to, equal to, or greater than their spousal benefit. In such circumstances, less (or potentially none) of the additional compensation received by the spouse will be ‘wasted’ by only increasing their own retirement benefit to equal their already-existing spousal benefit. Thus, salary shifting in this instance would potentially result in increasing the lower-earning spouse’s own retirement benefit such that the couple’s net Social Security benefits would be greater.

Ultimately, the key point is that to the extent a spouse can be legitimately hired for providing services to a working spouse’s company, salary-splitting strategies can be considered (or avoided) as a way to help the couple optimize their Social Security benefits, and offer some timing flexibility for spouses who may feel constrained by the rules of claiming spousal benefits. However, financial advisors should be aware of the potential limitations that these strategies have, especially because of the role that spousal benefits play in a couple’s total Social Security benefit.

Social Security benefits are a critical component of many couples’ retirement plans, making every dollar of potential benefit important. And even for others who have accumulated larger savings, Social Security benefits may be less important in terms of achieving the couple’s financial goals, but such individuals are often equally interested in getting every dollar out of the Social Security system as possible. Accordingly, helping clients navigate the complex maze of Social Security rules to maximize total benefits is a recurring theme for many advisors.

How Social Security Retirement Benefits Are Calculated

Social Security retirement benefits help workers who live long enough to replace a percentage of the income they earned earlier in life. In order for income to be ‘counted’ for Social Security benefits, it must be subject to the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax (and/or self-employment income subject to the Self-Employed Contributions Act [SECA]). Thus, in general, the greater the worker’s annual wages that are subject to FICA or SECA taxes, the greater the individual’s Social Security retirement benefit will be.

In 2020, workers may have a Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) – the amount the worker is entitled to receive as a Social Security retirement benefit at their Full Retirement Age – of as little as $0 (if, for instance, the worker did not earn 40 or more “credits” of coverage), and as high as $3,011 if they earn the maximum possible benefit.

For any particular individual, the retirement benefit amount is calculated based on their highest 35 years of (FICA- or SECA-taxed) earnings, determined by adjusting the worker’s earnings history for wage inflation that occurred in the past (to bring prior earnings into “today’s” dollars), adding the worker’s highest 35 years of inflation-adjusted earnings (subject to an annual cap, which is $137,700 in 2020, and itself is adjusted annually for inflation), and dividing that amount by 420 (the number of months in 35 years), to arrive at the worker’s Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). The highest possible AIME for an individual reaching Full Retirement Age in 2020 (age 66 and 2 months) is $9,636.

Nerd Note:

Technically, only wages earned in or before the year a worker reaches age 60 are wage-inflation-adjusted when calculating the worker’s Social Security benefit. Wages earned at 61 or later are included at their nominal amount but can still increase the worker’s PIA if they are one of the highest 35 years of earnings when compared to the pre-61 inflation-adjusted wage amounts.

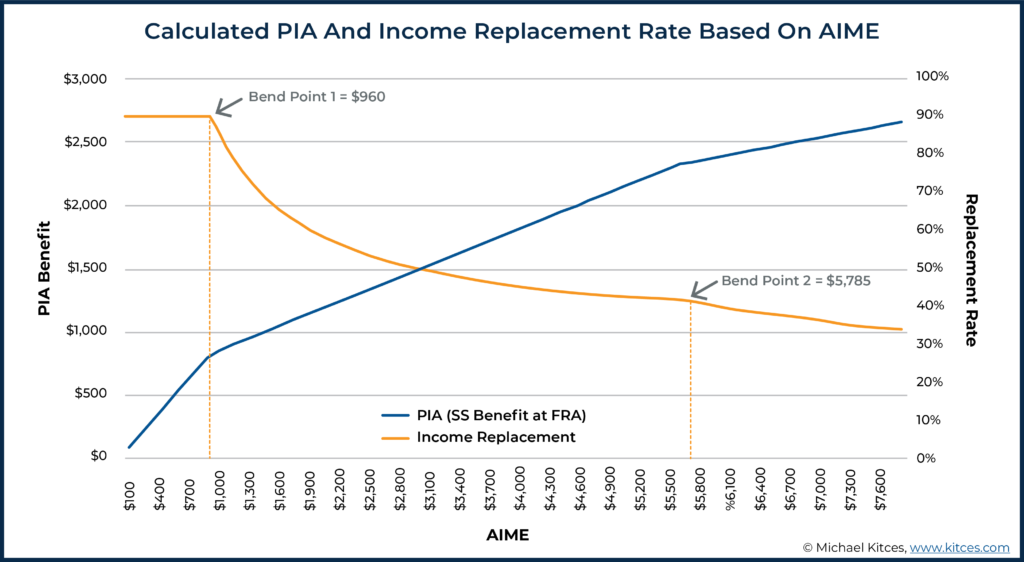

Once a worker’s AIME has been calculated, so-called bend points are applied to divide the AIME into as many as three separate tranches, each of which is then multiplied by a specified income replacement percentage, and added together to arrive at the worker’s PIA.

The first tranche is the total of the worker’s AIME that is equal to, or less than, the first bend point ($960 in 2020). This amount is multiplied by 90% as part of calculating the worker’s Primary Insurance Amount (PIA).

If the worker’s AIME exceeds the first bend point, any amount in excess of the first bend point, but equal to or less than the second bend point ($5,785 in 2020), will comprise the second tranche. This second amount is multiplied by 32% as part of calculating the worker’s PIA.

In the event that the worker’s AIME exceeds the second bend point, any excess beyond the second bend point creates a third tranche, which spans the threshold from the second bend point ($5,785/month) up to the maximum wages counted towards Social Security ($137,700/year, which equates to $11,475/month). This third amount is multiplied by 15% as part of calculating the worker’s PIA.

Finally, the (up to) three totals arrived at by multiplying each tranche of the worker’s AIME by the applicable percentage are added together. This becomes the worker’s PIA.

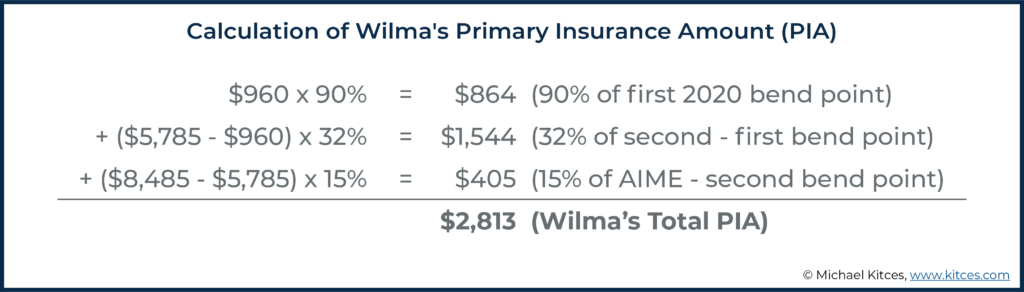

Example 1: Wilma will reach her Full Retirement Age (FRA) of 66 years and 2 months in 2020. Wilma has had consistently strong earnings throughout her career, and her AIME has been calculated at $8,485/month.

Accordingly, Wilma’s Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) equals $2,813, calculated as follows:

The presence of the bend points in the calculation of a worker’s PIA has the effect of diluting the value of earnings as they increase (which effectively is a form of Social Security “means testing” with higher income replacement rates for lower-income workers and lower replacement rates for higher-income workers). Notably, the first tranche of earnings, which comprises the portion of a worker’s AIME below the first bend point ($960 in 2020), is 90% ÷ 15% = 6 times more valuable than the ‘last’ (highest) earnings that boost a worker’s AIME over the second bend point ($5,785 in 2020). This is the primary driver behind Social Security retirement benefits replacing a greater percentage of a lower earner’s income in retirement than it does for higher earners.

Nerd Note:

A worker’s PIA is not necessarily the amount that they will receive as a retirement benefit. Rather, if an individual decides to claim their retirement benefit prior to their FRA (as early as age 62), then an actuarial adjustment will be applied to the PIA, and they will receive a reduced amount. By contrast, if an individual decides to claim their retirement benefit after their FRA (as late as age 70), then delayed credits of 8% per year (8%/12 per month) will be applied to their PIA, and they will receive a higher amount. For instance, an individual with a PIA of $2,000 who turns 62 in 2020 has a Full Retirement Age of 66 and 8 months. If they decide to claim their retirement benefit at the earliest possible time (age 62), an actuarial adjustment of 28.33% would be applied to their PIA, and they would receive a reduced retirement benefit of $2,000 x 28.33% = $1,432. If the same individual decided instead to delay benefits until age 70, they would receive a total of 4 years x 8% = 32% delayed credits = $2,000 + ($2,000 x 32%) = $2,640, plus any cost-of-living adjustments that would have been applied between age 66 and age 70.

A Worker’s Earnings Can Entitle The Worker’s Spouse To Benefits

In addition to a worker earning their own Social Security retirement benefit (at whatever replacement rates apply to their AIME to determine their PIA), if the worker is married, the same earnings can also entitle the worker’s spouse to a benefit based on the worker’s own employment record and their calculated PIA.

More specifically, if both spouses are alive (as they reach the age at which benefits can be claimed), the worker’s earnings will entitle the worker’s spouse to a spousal benefit.

An individual’s spousal benefit is equal to one-half (50%) of the worker’s PIA (as calculated above) if it is claimed at the spouse’s Full Retirement Age. If, on the other hand, the spousal benefit is claimed prior to the spouse’s Full Retirement Age (as early as age 62), then an actuarial adjustment will be applied, and they will receive a reduced amount. The worker must, however, actually claim their own retirement before the spouse can begin to receive their spousal benefit.

Nerd Note:

While workers with a retirement benefit can earn an 8% per year delayed retirement credit for waiting past their FRA, when it comes to spousal benefits, there are no delayed retirement credits. Instead, the age at which the worker claims their own retirement benefit has no impact on the amount of their spouse’s spousal benefit. Rather, the spousal benefit is always calculated on whatever the worker’s retirement benefit would have been if they had claimed the benefit at their FRA (their PIA), even if it’s not the retirement benefit they end out receiving after age-based adjustments.

It’s also important to note that, if the worker dies, as long as the couple was married at least nine months (or less, in the event the death is due to an accident), the surviving spouse will be entitled to a survivor benefit.

Nerd Note:

Unlike spousal benefits, which are based on the worker’s PIA, the survivor benefit is calculated, in part, using the worker’s actual retirement benefit. Therefore, it is increased or decreased (but not below 82.5% of the deceased worker’s PIA) for any age-based adjustments if the worker begins benefits earlier or later than their FRA. This amount, known as the “original benefit”, may be (further) reduced if the surviving spouse claims the survivor benefit prior to their own FRA.

Individuals Can Be Entitled To More Than One Type Of Social Security Benefit At The Same Time

If both members of a married couple have worked long enough (earned 40 or more Social Security credits), each spouse will generally be entitled to two benefits (technically referred to as “dual entitlement”): their own retirement benefit (calculated based upon their own earnings history), and a spousal benefit (calculated based upon the earnings history of their spouse).

Social Security does not pay the cumulative amount of both benefits for such individuals, though; rather, when an individual files for either their own retirement benefit or spousal benefit, they will be deemed to be filing for both benefits at the same time and will receive whichever is the higher of the two amounts.

As such, a lower-earning spouse’s own earnings history is often non-accretive to the couple’s combined potential Social Security benefit. It simply doesn’t create any additional benefit. More specifically, if an individual’s spousal benefit is higher than their own retirement benefit, their benefit will be the same as if they had not worked at all!

Example 2: George and Jane are a married couple (and have been married for more than one year). George will reach his Full Retirement Age (FRA) in November 2020, while Jane will reach hers the following month, in December 2020.

George has consistently been a high earner and has a PIA of $2,800. Jane also worked, but took some time out of the workforce to help raise their children when the children were young. She earned less throughout her career; accordingly, her PIA is $1,000.

George plans to begin claiming his retirement benefit at his FRA. Accordingly, he will begin receiving monthly checks of $2,800.

Jane also plans to begin collecting Social Security benefits upon reaching her FRA. Assuming she does so, Jane will receive a total benefit of $1,400 per month. Her monthly benefit would be comprised of her own $1,000 retirement benefit, plus an additional $400 ‘excess spousal benefit’ to cover the difference between her own retirement benefit and a full spousal benefit (50% of George’s $2,800 PIA).

Notably, though, this $1,400 monthly benefit is exactly the same benefit that Jane would be entitled to as a ‘pure’ spousal benefit, as determined solely based upon George’s lifetime earnings. Therefore, Jane’s own earnings history provides no additional benefit for the couple, and their cumulative Social Security benefits will be the same as if Jane had never worked at all!

The False Promise Of Splitting A Salary To Boost A Couple’s Net Social Security Benefits

Oftentimes, when a married individual is the owner of a business, there is a temptation to split the salary from the business (or in the case of a sole proprietorship in a separate-property state, the profits of the sole proprietorship, by creating a partnership) between both spouses. The thought is that by splitting the total wages between both spouses, less of the total wages paid will go towards generating the tranche of the AIME that returns 15 cents (and/or 32 cents) on the dollar when calculating the individual’s PIA and more of the total wages will go towards generating the tranches of the AIME that return 90 cents (and/or 32 cents) on the dollar.

This is often particularly appealing when the total salary paid is below the maximum annual amount of earnings subject to FICA taxes ($137,700 in 2020), as splitting the salary will not lead to any increase in total FICA taxes paid (because the income is fully subject to FICA taxes either way, regardless of whether/how it is split). By contrast, where wages in excess of the annual maximum amount of earnings subject to FICA taxes are split, the split will cause additional wages to become subject to the tax, and is often enough of a deterrent, on its own, to eliminate the desire to split the wages.

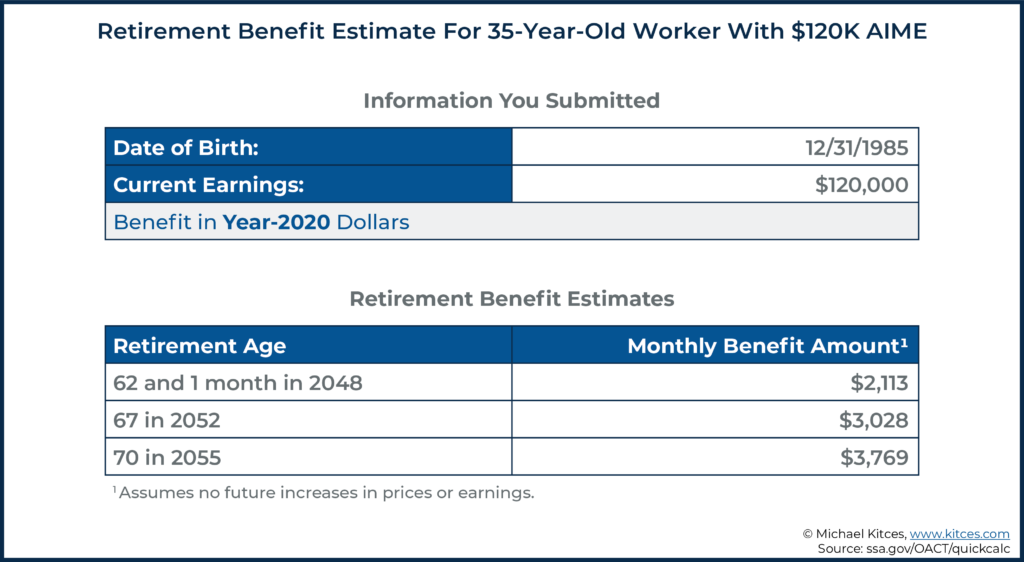

Example 3: Betty is 35 years old and is married to Barney, who is also 35 and a stay-at-home dad (who is not otherwise accruing Social Security benefits by staying at home and not working).

Betty is the owner of Happy, Inc., an S corporation from which she currently pays herself a salary of $120,000, all of which is subject to FICA tax.

In addition, Betty enjoys profits from Happy of an additional $150,000, none of which are subject to FICA taxes (as while profits from S corporations are subject to ordinary income tax rates, they are not subject to FICA taxes).

After reading an article about how an individual’s Social Security retirement benefit is calculated, Betty gets an idea. Instead of continuing to pay herself a wage-inflation-adjusted salary of $120,000 annually, she considers splitting her salary evenly, paying herself $60,000, and hiring her spouse, Barney, at an equivalent salary of $60,000.

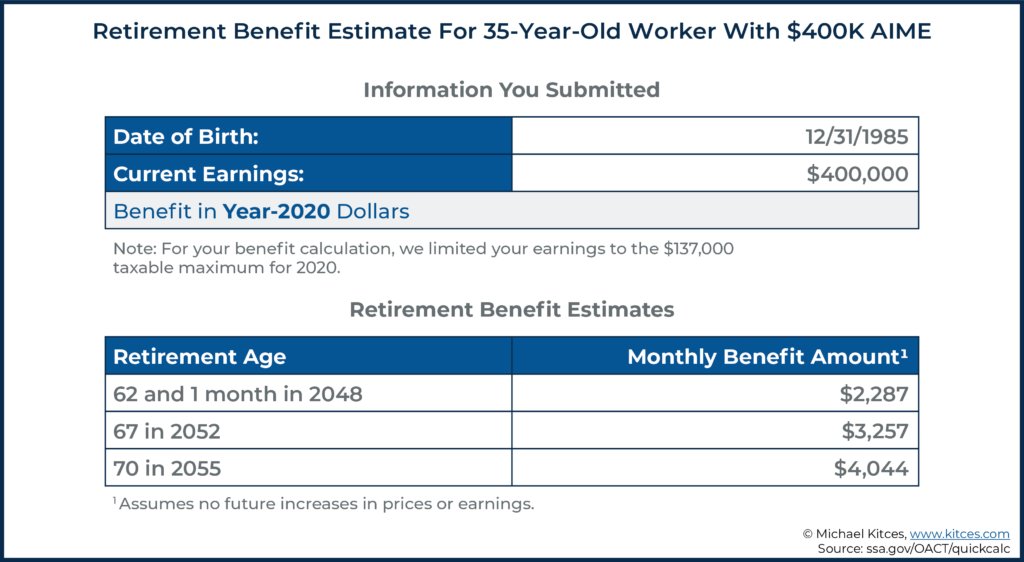

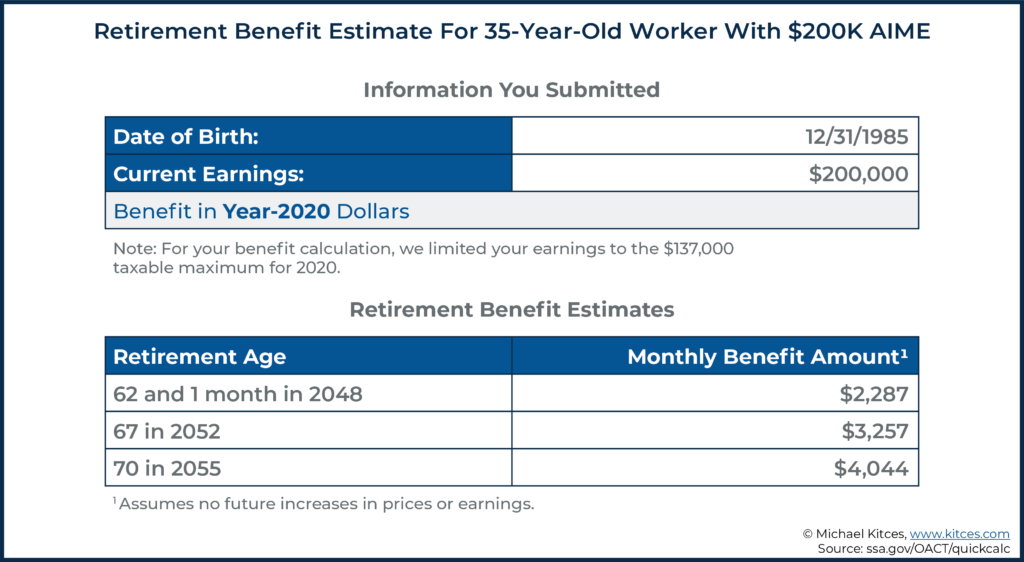

On the surface, this would seem like a logical idea. Notably, using the “Quick Calculator” available on the Social Security Administrations website, we can see that a 35-year-old with 35 or more years (the number of years’ wages used in calculating the AIME) of $120,000 of present-day, wage-inflation-adjusted earnings would have a PIA of $3,028.

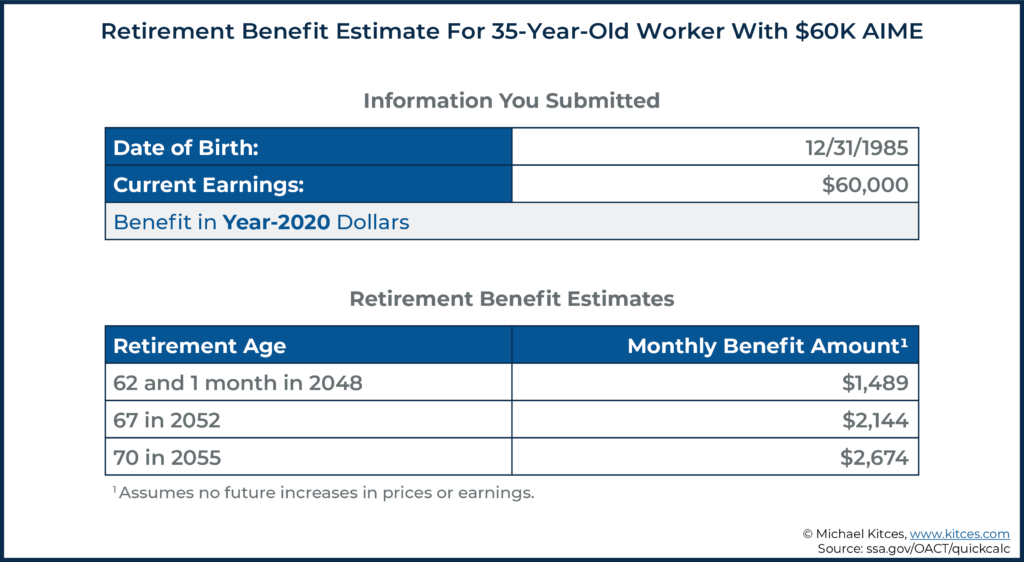

Conversely, by using the same calculator, we can see that if the same individual earned $60,000 of present-day, wage-inflation-adjusted earnings for 35 or more years, the PIA would be reduced, by ‘only’ to $2,144.

So, while the salary was cut in half, the individual’s Social Security retirement benefit would retain $2,144 / $3,028 = 79.62% of its original value.

Multiply that $2,144 PIA by two, since both spouses (Betty and Barney) would have income of $60,000 annually, and we arrive at a total Social Security retirement benefit, at the couple’s Full Retirement Ages, of 2 x $2,144 = $4,288. That’s well more than the $3,028 PIA that the same $120,000 of total earnings would generate if they were paid to just a single individual.

So splitting salaries results in a combined PIA that is greater than that resulting from the unsplit salary… Home run, right?

Not so fast. As a matter of fact, more often than not, the ‘planning strategy’ above is more of a ‘swing and a miss for strike three’ than it is a ‘home run!’

But why?

Simply put, it ignores the existence and value of the spousal benefit.

Recall that a spousal benefit is a ‘built-in’ benefit that an individual is entitled to, based upon the earnings history of a worker. The spouse (receiving the spousal benefit) does not need to work – ever – in order to receive such a benefit. Accordingly, if an individual will be entitled to a spousal benefit, their own earnings history becomes largely irrelevant unless it can help them generate a benefit larger than the spousal benefit they will already be entitled to receive by ‘default’.

Stated differently, wages from a high-earning spouse that are shifted to a lower-income spouse may be calculated in the lower-income spouse’s own retirement benefit at a higher replacement rate (than would have been the case if the wages were paid to the higher-earning spouse), but when the spouse is dual-entitled, that shift may not actually result in a higher (cumulative) benefit, because the spouse’s much-lower retirement benefit (based on the wages that were split and shifted to them) may be less than what the spousal benefit would have been had the salary not been split at all! In other words, the higher spousal benefit will overwrite the lower retirement benefit anyway… so making the retirement benefit higher is a moot point (when it’s going to be overwritten anyway)!

In fact, in many situations, it’s impossible to pay a lower-earning spouse enough wages to produce a retirement benefit in excess of the spousal benefit they are already on track to receive, absent the salary shift. Accordingly, any shift in salary actually produces lower cumulative Social Security benefits for the couple.

For instance, in reviewing Example 3 above, where, absent a salary shift, Betty would have a PIA of $3,028, Barney would ‘automatically’ be entitled to a spousal benefit of $3,028 ÷ 2 = $1,514. Therefore, if Barney earns compensation of his own – whether it be from Betty’s business or from an unrelated employer – it would not increase the total benefit available to the couple at their FRA (Betty’s retirement benefit + Barney’s spousal benefit) unless Barney’s earnings history produces a benefit of more than $1,514.

And, as it turns out, it’s impossible to shift enough of Betty’s salary to Barney to produce a larger cumulative Social Security benefit than they would have enjoyed by simply continuing to have Betty earn her full $120,000 of annual compensation each year (and having Barney receive 50% of that amount as a spousal benefit)!

More specifically, as the chart below shows, a small shift of $10,000 in salary from Betty to Barney each year results in a markedly lower cumulative benefit. As the income shifted from Betty to Barney increases, the couple’s total retirement benefit income shifts down from $4,542/month towards $4,288. As more of Betty’s compensation is shifted and salaries equalize, the difference diminishes, but it never actually produces a greater benefit than the couple would have enjoyed by doing absolutely nothing!

How Splitting Salaries That Are Above The Social Security Wage Base Can Increase Cumulative Social Security Benefits… But Also Increase FICA Tax Liabilities

It’s worth noting that this phenomenon – where splitting salaries cannot produce a net higher cumulative benefit at Full Retirement Age – is generally true for situations in which the higher earner’s compensation is less than maximum compensation subject to FICA taxes. Where an individual’s compensation is substantially higher, though, splitting compensation could produce a net increase in Social Security benefits. But it would also come at the expense of a significant increase in annual FICA tax liability.

For instance, an individual with $300,000 of annual compensation (adjusted for wage inflation) for 35 years would be entitled to a maximum Social Security benefit. Furthermore, they would be entitled to such a benefit even though ‘only’ the first $137,700 of wages (in 2020) would be subject to the FICA tax.

If such an individual were married, their spouse would generally be entitled to a spousal benefit of half of the maximum PIA at their (the spouse’s) Full Retirement Age. Accordingly, the cumulative Social Security benefit received by the couple when they reached their Full Retirement Ages would be 1.5 times the maximum PIA, all funded via the one working spouse’s ‘maximum-earnings’ history.

Suppose, however, that this couple split the $300,000 of compensation evenly, $150,000 per spouse. Would that produce a net higher Social Security benefit at Full Retirement Age?

Sure. Because at $150,000 of annual compensation each, both spouses would have enough annual compensation to have a maximum PIA. Accordingly, the primary earner would not face any reduction in benefits (because she is still above the Social Security wage base earning the maximum PIA), but the spouse would earn the maximum 100% PIA benefit – which is certainly higher than ‘just’ 50% of the primary earner’s PIA. As a result, instead of effectively earning 1.5X the maximum PIA (100% for the primary earner plus 50% as a spousal benefit), the couple would earn 2 times the maximum PIA at Full Retirement Age instead.

Example 4: Recall Betty and Barney, from Example 3, who are married and are each 35 years old. Suppose that Betty’s company, Happy Inc., suddenly takes off, and Betty begins paying herself a salary of $400,000 annually.

Accordingly, using the Quick Calculator available on the Social Security website, we can see that Betty’s PIA is projected to be $3,257. Barney’s spousal benefit, therefore, would be $3,257 x 50% = $1,628.50, giving the couple projected cumulative Social Security benefits of $4,885.50 when they reach their Full Retirement Ages.

Suppose, however, that instead of paying herself a salary of $400,000 annually, Betty splits her salary evenly between herself and Barney. Since Betty’s salary would continue to be above the $137,700 maximum earnings subject to the FICA tax (for 2020), there would be no impact on her future PIA. It would remain the same at $3,257.

However, since Barney would now also have a salary of $200,000 annually, he too would have a projected PIA of $3,257. Accordingly, the couple’s cumulative Social Security benefits at their FRAs would be $3,257 x 2 = $6,514. That’s $1,628.50 per month more than was the case when Betty only paid herself!

Thus, in Example 4, Betty and Barney would have increased their cumulative Social Security benefit by ($6,514 – $4,885.50) ÷ $4,885.50 = 33.33%, where splitting salaries results in both spouses having a maximum PIA based on their own retirement benefit, versus not splitting salaries results in one spouse having a maximum PIA for purposes of calculating their retirement benefit and the other having 50% of the maximum PIA for their spousal benefit.

However, in doing so, they will have doubled their annual FICA tax liability. In Example 4, above, for instance, Betty is subject to personal FICA taxes of $137,700 x 6.2% = $8,537.40, regardless of whether she pays herself a salary of $400,000 or $200,000. However, if Betty opts for the latter because she pays Barney a salary of $200,000 as well, then Barney will also be personally liable for FICA taxes of $8,537.40 in 2020.

But even that doesn’t tell the whole story, because Betty’s business has to match the FICA taxes paid by its employees. Accordingly, splitting Betty’s salary and putting Barney on the payroll for $200,000 produces a net increase in FICA tax responsibility for the couple of $8,537.40 x 2 = $17,074.80!

Do that annually until FRA, and it’s nearly $550,000 (in today’s dollars) of additional FICA taxes that will be owed.

And in return for those contributions, what do Betty and Barney get? An ‘annuity’ payment of $1,628.50 per month.

It’s hard to imagine many individuals would opt for that trade-off voluntarily… especially when you consider the additional risk that, if either spouse dies, the higher cumulative benefit will ‘die’ with them (as either way, the survivor would be entitled to a benefit calculated using ‘max-earnings’).

Stated differently, that $1,628.50 is an ‘annuity’ payment that will only be paid for as long as both spouses are alive. When the first spouse dies, so too does that ‘annuity’ payment!

Nerd Note:

An S corporation is required to pay reasonable wages to individuals who provide services to the S corporation. The most common issue related to an owner’s compensation paid by an S corporation is paying too little in wages, typically in an effort to have more of the total income received from the S corporation escape FICA taxes. However, it’s also impermissible to pay someone, including a spouse, wages that are unreasonably high for the services provided. Accordingly, a spouse hired (that is on payroll) by an S corporation must actually provide some sort of service to the company. “Reasonable,” however, is a fairly subjective term, and as such, the “reasonable salary” that an individual can justifiably receive is often fairly broad in range. Throughout this article, we shall assume that any salary splitting (or non-splitting) can be justified by the services that the paid individuals are providing to a company.

Limited Situations Where Spousal Salary Shifting Can Be Beneficial

As outlined above, in general, it does not make sense to split a ‘single’ wage across two workers in order to try to increase cumulative Social Security benefits.

However, as with most planning strategies, there are a variety of exceptions to the general rule. Three such exceptions include 1) when a lower-than-‘max-earnings’ worker’s compensation will not be a top-35 income year, 2) when additional flexibility in the timing of claiming is desired, and 3) when the lower-earning spouse has enough of their own income to already be close to the spousal benefit amount.

Lower-Than-Maximum Earnings For The Worker Spouse – When Compensation Is Not Included In A Top-35 Year

One situation where it can make sense to shift compensation between spouses is when the worker spouse’s compensation is below the maximum compensation subject to FICA tax for the year, and the compensation isn’t high enough to be one of the worker’s top 35 years of wage-inflation-adjusted compensation.

Nerd Note:

An individual’s earnings history can be found on their Social Security statement. Those earnings can then be multiplied by the appropriate increases in the Average Wage Index to compare such amounts to the present-day, nominal salary, to determine if the present-day compensation will be one of the top 35 years of earnings.

Recall that an individual’s retirement benefit is calculated using the highest 35 years of wage-inflation-adjusted compensation. As such, any compensation earned in years that do not ‘crack’ the highest 35 years of such compensation will provide no benefit to increasing the worker’s retirement benefit. In short, there’s no Social Security benefit upside to keeping that compensation with the worker spouse.

In addition, the worker’s compensation is less than the maximum compensation subject to FICA tax for the year, shifting any (or even all) of the compensation to their spouse will not increase the total FICA taxes paid by the couple. In short, there’s no FICA tax downside to shifting that compensation to the spouse.

Accordingly, to the extent such a shift in compensation can be reasonably justified by services provided by the spouse to the worker spouse’s company, it’s a no-lose proposition to potentially increase the PIA based on the spouse’s own work record.

In the end, the compensation may not be enough to allow the spouse’s own retirement benefit to exceed their own spousal benefit, especially when the spouse’s earnings history is lower than the worker spouse’s, in which case, from a Social Security benefit standpoint, it’s a wash. But as the old saying goes, “It can’t hurt to try!” And it’s at least possible that the additional earnings will result in a higher benefit for the spouse in the future (when added to whatever other earnings they may generate for Social Security benefits in the future).

More Flexibility In Timing Of Claiming Is Desired

One big benefit of a Social Security retirement benefit versus a spousal benefit is that, in general, such a retirement benefit can be claimed whenever the worker wants between the ages of 62 and 70.

By contrast, as noted earlier, a spousal benefit can only be claimed at the time – or sometime after – the worker spouse (whose earnings history is used to calculate the spousal benefit) has claimed their own retirement benefit.

Accordingly, if the worker spouse decides to wait until they are 70 in order to maximize the value of their own retirement benefit (and, if they are the first to die, the survivor benefit for the spouse), their spouse will not be able to claim a spousal benefit until that time as well.

This can be particularly frustrating for couples who are close in age, or where the lower- or non-earning spouse is older than the worker, as there is no dollar advantage (through delayed credits) for waiting to take a spousal benefit beyond an individual’s Full Retirement Age (as there is with one’s own retirement benefit).

Example 5: Bamm-Bamm and Pebbles are married and are of the same age. They will each reach their Full Retirement Age in 2020. Bamm-Bamm’s PIA is $2,500, while Pebbles did not work enough to have her own retirement benefit. As such, she will (eventually receive) a spousal benefit of $2,500 x 50% = $1,250.

Bamm-Bamm believes that there is a strong likelihood that he and Pebbles will have reasonably long lifetimes. As such, he plans to delay receiving his Social Security retirement benefit until age 70. Unfortunately, that means that Pebbles must also wait until she is age 70 to claim her spousal benefit.

During that time, Bamm-Bamm’s retirement benefit will increase (as delayed credits and any cost-of-living adjustments are applied), but Pebble’s spousal benefit will remain $1,250 (plus any cost-of-living adjustments).

Which means that by waiting until Bamm-Bamm’s age 70, Pebbles will simply forfeit $1,250/month of benefits without enjoying any increase in future benefits for having waited!

In situations when spouses desire more flexibility to claim their Social Security benefits (compared to the circumstances such as in Example 5 above), splitting salaries can help alleviate the problem. For instance, if Pebbles had earned ‘just’ enough to generate her own $1,250/month retirement benefit by splitting salary with Bamm-Bamm, then her benefits themselves would not have increased… but the couple’s benefits would end out being higher because Pebbles could claim her $1,250/month for the 4 years that Bamm-Bamm was waiting for his own benefit (and earning his Delayed Retirement Credits).

The split may still have a negative impact on the overall maximum potential benefit the couple might receive from Social Security, but having the freedom and flexibility to claim benefits at different ages could make it a worthwhile ‘investment’ for a client.

Lower Earner’s Own Benefit Is Close (Or Above) Spousal Benefit

In some situations, it’s not a matter of one spouse being the sole ‘breadwinner’ and the other spouse not working at all. Rather, one spouse may simply be more highly compensated than their spouse. In such situations, where the lower earner’s own retirement benefit is already equal to or greater than the spousal benefit, a shifting of some of the higher-earning spouse’s compensation to the lower-earning spouse can actually produce a higher cumulative Social Security benefit.

Notably, the primary issue with shifting a working spouse’s compensation to their spouse is that, depending on the difference between each spouse’s PIA, a good amount of the shifted compensation may be needed just to get the spouse’s own retirement benefit equal to the spousal benefit that they would have received, absent any action. In other words, a lot of the shifted income may be ‘wasted’ because it may take a large shift in compensation to move the PIA needle for the spouse’s retirement benefit to exceed their spousal benefit.

For instance, in Example 3, above, Barney was entitled to a $1,514 spousal benefit without any compensation of his own. As Chart 1 (shown earlier) indicates, however, even when Barney was receiving a salary of $30,000, his own retirement benefit of $1,350 was still less than his initial spousal benefit of $1,514.

Accordingly, the first $30,000+ of compensation paid to Barney was ‘wasted’ in an effort to merely get his own benefit to equal the spousal benefit to which he’d have already otherwise been entitled.

If, however, the spouse has their own lower compensation already, and a compensation shift would produce a benefit close to, or above, their spousal benefit, then the shift may be much more financially ‘satisfying’. More specifically, if, say, the spouse’s own earnings already produce a retirement benefit that is equal to their spousal benefit, then each additional dollar of compensation they receive will actually increase their own retirement benefit (rather than just helping it reach the amount of their spousal benefit, to begin with).

Accordingly, if the lower-earning spouse would see more of that income replaced as a Social Security benefit (e.g., the income would go towards a tranche of the spouse’s AIME with a higher replacement rate in determining their own retirement benefit) than the worker spouse, the couple’s cumulative net Social Security benefit will increase.

Example 6: Recall, once more, Betty and Barney from Examples 3 and 4, who are each 35 years old.

In Example 3, Betty was receiving compensation of $120,000, while Barney was earnings $0, and we were able to show that no matter how much salary Betty shifted to Barney, the couple did not see an increase in total Social Security benefits at their FRAs.

But what if, instead of no compensation, Barney had compensation of $40,000 per year? Using Social Security’s Quick Calculator, we can see that Barney would be projected to have a PIA of $1,615.

That actually changes the ‘equation’ quite a bit, because none of Barney’s salary would be wasted just helping him get a retirement benefit equal to his spousal benefit. His existing earnings already do that.

Accordingly, if Betty were to shift $20,000 of her ($120,000) salary to Barney, her PIA would decrease from $3,028 to $2,780, or a total of $248. Meanwhile, by increasing his compensation from $40,000 to $60,000, Barney’s PIA would increase from $1,615 to $2,144, or a total of $529!

In the situation in Example 6, for every dollar of compensation that Betty shifted from herself to Barney, Barney’s PIA increased by roughly double the amount that Betty’s PIA decreased. A win!

Well, maybe…

It’s not a ‘perfect’ plan. Of course, so little rarely is.

Because while such a shift can increase the PIA for the spouse receiving the additional compensation more than it reduces the worker spouse’s PIA, in order for them to see the net benefit, both spouses have to remain alive for it to work out! As when the first spouse dies, the survivor will keep the (worker’s) higher benefit amount. Thus, if either spouse dies early in retirement – or before – the remaining benefit amount will be lower than it otherwise would have been, had no shift in compensation taken place.

Social Security is often referred to as one of the three legs of the ‘retirement income stool’, along with pension income and personal savings. These days, outside of government work, pensions are extremely rare, turning the three-legged stool into a two-legged stool for most workers. Accordingly, Social Security is an increasingly valuable part of many individual’s retirement plans.

The good news for workers is that Social Security benefits remain a cost-of-living-adjusted, tax-efficient (as no more than 85% of Social Security benefits are taxable), lifetime annuity. The downside is that in order to get the most out of the system, it’s necessary to navigate its many rules.

Oftentimes, what seems to make sense ‘on the surface’ may no longer make sense once individuals dig a bit deeper. Such is the case with ‘splitting’ salaries between spouses.

While the allure of such a move can seem obvious when one spouse’s replacement rate is higher than the other’s, the built-in default benefit for the lower-earning spouse (i.e., the spousal benefit) often makes such a shift in income a net-negative. Nevertheless, in limited circumstances, such a shift can provide a couple with the opportunity to receive a net increase in Social Security benefits and/or more flexibility from a time-of-claiming perspective.

Leave a Reply